This article is part of our March 2015 special report on adjunct professors. See the results of our survey and read related stories here.

I am on the phone with a humanities professor at a small, nationally revered liberal-arts college, and she is telling me about the seltzer situation in the faculty lounge.

“You know, the dean said we need to get the beverages out of there.”

“And that’s, like, a hygiene thing?”

“No, it’s because they’re worried we’re spending too much on Diet Coke and those aluminum cans of seltzer.”

“Oh.”

“And the president just replaced his hood ornament with a Fabergé egg. Our Manhattan consulting firm said it was the only way to upstage Dartmouth.”

OK, I made up the egg thing, but the Manhattan consultants are real enough. In fact, I’m pretty sure it was the consultants who recommended that the college “economize” by decarbonating its faculty—a task that got easier once the consultants had helped the college eliminate a terrifying number of teaching positions.

The corporate university is successfully divesting from such frivolities as club soda—and from professors, as well. In their place marches the great academic underclass, the adjuncts or lecturers or other species of contingent labor, who now account for more than half of all post-secondary teaching positions in the country.

Become friendly enough with the moneymen and representatives of the political class, and you’re guaranteed a series of headhunting, fundraising, budget-slashing gigs that will keep your kids in salmon-colored slacks through business school.

Last month saw the first National Adjunct Walkout Day, denoted on social media by the hashtag #NAWD (pronounced “gnawed,” no doubt—chewed up and shortly expectorated). Everyone on campus feels a bit gnawed lately, but the adjuncts have it particularly rough—no benefits, spotty prospects for job security, a half-salary cobbled together from teaching appointments at multiple schools in the region. And these same poor “academic helots” (to use a phrase from William Deresiewicz) are the ones teaching your kids.

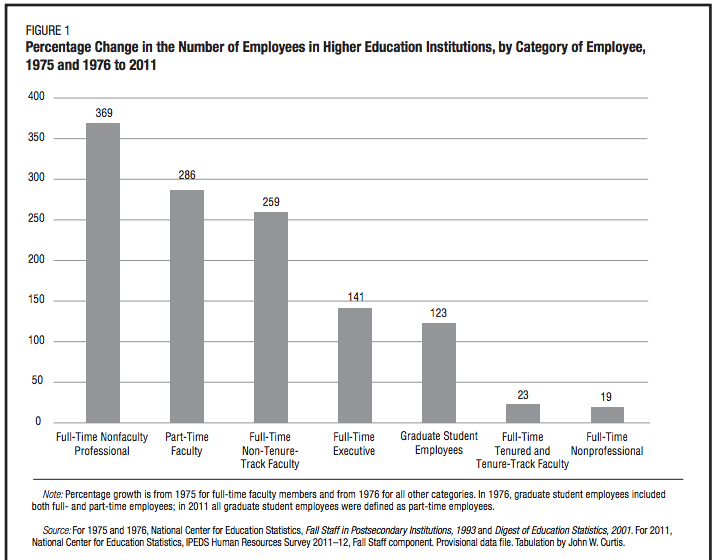

Since 1969, the number of adjuncts has tripled in the United States. The University at Buffalo is reasonably representative: As of 2009, 65 percent of faculty there are adjuncts. This 40-year decline in academic appointments coincides precisely with the corporatization of the university, as administrations ballooned and schools vested ever-greater authority in their supervisory boards—boards that generally comprise titans of business and finance and obey the strategic orthodoxies of management school. Between 1975 and 2005, faculty hires barely kept pace with growing enrollments. Over the same period, administrative posts have trebled or more.

According to data from the National Center for Education Statistics, full-time non-faculty professionals grew by 369 percent; tenured or tenure-track faculty positions grew by a mere 22 percent. Full-time, non-tenure-track faculty grew by 259 percent, and part-time faculty by 286 percent. Those last two numbers are your academic helots—the result of trickle-down corporate wisdom, an emphasis on short-term goals, and a tendency to balance the budget starting from the wrong end.

Too often, the problem begins at the level of the executive board, usually run by representatives of consultancies and hedge funds; the rhetoric, the aggressive but narrow ambition of the corporate world, these become the university’s guiding principles. By these same principles, U.S. News & World Report lists becomes like Forbes—the rankings come first, and U.S. News bases 15 percent of a university’s grade on “prestige,” which we all know you can’t teach but you sure can buy. Chasing short-term gains in the early aughts, Wall Street brought the country to its knees; these same so-called market experts are bestowing ungainly, top-heavy budgets on the universities they oversee.

THE STATE OF ADJUNCT PROFESSORS

• Survey: 62 percent of adjuncts make less than $20,000 a year from teaching.

• The Professor Charity Case: PrecariCorps wants to draw attention to the plight of adjunct professors.

• How Colleges Misspend Your Tuition Money: You know tuition is on the rise, but you keep hearing that professors aren’t paid fairly. Where’s the money going?

• Adjunct Professors and the Myth of Prestige: Notes from 20 years of adjunct politics.

The 2012 scandal over the firing of Teresa Sullivan, president of the University of Virginia, illustrated the grim discrepancy between the aims of the corporate university and the ideals of the teaching university—remember all that blather about “strategic dynamism”? Sullivan, in fact, is an especially nice example here: She is a sociologist of class and poverty—subjects that lawmakers are actively pushing under the carpet in public universities across the country—and had clashed with the board because, as the Washington Post reported, “They felt Sullivan lacked the mettle to trim or shut down programs that couldn’t sustain themselves financially, such as obscure academic departments in classics and German.” (Thomas Jefferson, an enthusiastic classicist, would likely applaud such lack of “mettle.”) After enormous public outcry, Sullivan was re-instated, and the teaching faculty at UVA have, for the moment, an advocate in their president.

Elsewhere, instructors fare less well, as a professional class of executive administrators continue their zig-zagging ascent through the cursus honorum of seven-figure appointments: Become friendly enough with the moneymen and representatives of the political class, and you’re guaranteed a series of headhunting, fundraising, budget-slashing gigs that will keep your kids in salmon-colored slacks through business school. Go and count the university presidents who have accepted massive bonuses and awarded concomitant raises to upper-level administrators while—sometimes in the same public statement—freezing faculty raises and hires across all departments. As Benjamin Ginsberg reported in the Washington Monthly in 2011:

Facing $19 million in budget cuts and a hiring freeze, Florida Atlantic University awarded raises of 10 percent or more to top administrators, including the school’s president. In a similar vein, in February 2009, the president of the University of Vermont defended the bonuses paid to the school’s twenty-one top administrators against the backdrop of layoffs, job freezes, and program cuts at the university.

Just think about all the ways universities could economize in the other direction—cutting non-essential expenses in order to strengthen teaching. The University of Iowa spent over $200,000 this year on a search firm for its new president; University of North Carolina (where I am a teaching fellow, and technically therefore contingent labor) paid $782,000 to a public relations firm after a recent athletics scandal. (I haven’t even tallied the hours-billable logged during the investigation of the scandal and subsequent drafting of the Wainstein Report.) Schools pay $100,000 and more for commencement speeches from Katie Couric or Jeff Foxworthy or Drew Carey. Somewhere, someone paid Adam Carolla $50,000 to do the same thing. Dr. Phil used to get $200,000, as when he spoke in 2011 at the University of North Texas.

Duke University estimates the starting cost of an endowed chair at $1 million. It isn’t hard to imagine how many full-time faculty members—with benefits—we could hire if we sacrificed the occasional headhunter, or Drew Carey. Milton Greenberg is right: You don’t need a search firm to hire a president. But some presidents—especially if they’ve been hand-picked by the board with a very expensive search process mounted just for the sake of appearance—refuse to buck the new orthodoxy of corporation-like spending. This indicates a severe problem in short-term vs. long-term planning, a typical disease of Wall Street now running through the veins of the college, hurting students and instructors the hardest.

The adjunct economy spans people living above, below, or athwart the poverty level: Ph.D.s on food stamps, Ph.D.s with family money, or Ph.D.s who supplement their income through tutoring, yoga instruction, journalism, etc. And they’re not poorly paid due to lack of talent; for some adjuncts, in fact, it’s precisely because they’re such good teachers that they haven’t achieved preferment in their departments. (You need to write books if you want tenure, and how can you write books when you’re teaching four classes at three different universities?)

Since 2008, American schools have been facing the problems that faced English universities under the early onslaughts of Thatcherism, when Britain began slashing its teaching budgets and what Claude Rawson describes as the “great Oxbridge exodus” sent some of Britain’s greatest scholars to America. But neither Rawson nor Thatcher could have predicted how labor at American universities in the 21 century would stratify into something very like a class system, with administrators, fundraisers, and wheel-greasers the aristocracy, academic deans the gentry, and non-tenured instructors the lumpenproletariat.

Someone like George Will would argue that the current bureaucracy creep is some kind of post-hippie comeuppance for the academy, another big-government intrusion in the marketplace.

In fact, it is the corporatization of the university—re-organized into a service provider, with its committees of “strategic planning,” its mission ever-more circumscribed by capitalist euphemism. This corporatization process has led to the teaching crisis. Any solution to the adjuncting dilemma must reject the premise of corporate wisdom that led us here in the first place.