New research from Brown University, published in the Journal of Proteome Research, presents a much broader picture than previously realized of how nicotine impacts cell communication throughout the mammalian nervous system.

The researchers are also hopeful that their data could help in the development of better treatments for smoking addiction and disease. “It opens several new lines of investigation,” lead author Edward Hawrot was quoted in a press release announcing the findings.

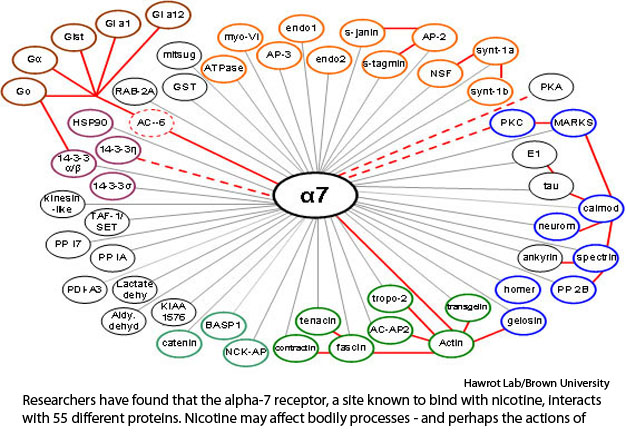

The target of the study was mouse brain tissue, specifically the alpha-7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor — where nicotine bonds with the surface of cells when it comes into the body — because a very similar receptor resides in the human brain. Hawrot’s laboratory studied mice genetically engineered to lack the alpha-7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor and compared them with normal mice. The researchers discovered that 55 proteins were found to interact with the alpha-7 nicotinic receptor; the connections had not previously been known to scientists.

“This is called a ‘nicotinic’ receptor, and we think of it as interacting with nicotine, but it likely has multiple functions in the brain,” said Hawrot, professor of molecular science, molecular pharmacology, physiology and biotechnology at Brown. “And in various, specific regions of the brain this same alpha-7 receptor may interact with different proteins inside neurons to do different things.”

The discovery means that the alpha-7 receptors play a much bigger role in the body than previously thought, and that nicotine may impact bodily processes far beyond previous estimates.

The study, too, has implications beyond just smoking addiction. Recent genetic studies of schizophrenia have associated the condition with a block of “missing” or “deleted” genes — including the gene for the alpha-7 receptor. The connection, while not conclusive, could point to new strategies for treatment, Hawrot said.

Sign up for our free e-newsletter.

Are you on Facebook? Become our fan.