A honeymoon, at least by design, is a celebration. But it’s also a time of testing — a tryout that reveals who holds the power, how it will be exercised and what sort of balance will be struck between cooperation, capitulation and control. This is all the more true when the newly christened union involves a president and his various paramours: the public, the media and the Congress.

According to conventional wisdom forged during the tumultuous yet remarkably productive first 100 days of Franklin Roosevelt‘s administration, the “honeymoon period” can set the tone for an entire presidency. But is the honeymoon real, and are its effects truly lasting?

Hazardous to Political Health

Richard Neustadt was a honeymoon skeptic. The late Harvard University scholar and adviser to three presidents was a widely admired authority on executive-branch power. (He famously said, “Presidential power is the power to persuade.”) Writing in the March 2001 Presidential Studies Quarterly, he asserted that honeymoon periods “are marginal, at best, in deciding a new president’s success with legislation.” He argued in the essay that the instinct to cross party lines and think in nonpartisan terms fades after about six months, but “final action on most controversial bills” occurs later in a session.

Neustadt further noted that a new chief executive “will be ignorant of many things he urgently needs to know, yet can learn only by experience.” Because of this, he concluded, the early days of a presidency are “marginally advantageous” but “exceptionally hazardous.”

Within a month of taking office, he wrote, Ronald Reagan sent to Congress a sweeping series of tax cuts — before his own budget office could calculate their impact. This legislation “set the stage for outsized budget deficits in later years. (These were) the unintended consequences of a huge and novel effort, pursued in haste.” Bottom line: Pushing for quick legislative successes is enticing, but a new administration should avoid that temptation.

Carried Over the Threshold

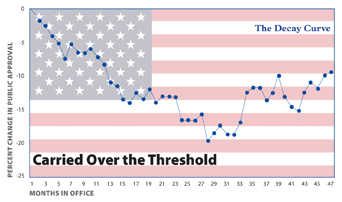

The president’s presumed power during his first months in office flows from his high approval ratings. But is presidential popularity at its peak during the first months of a new administration? The answer is absolutely yes. The late Barbara Hinckley, a political scientist at New York University and Purdue University, charted the approval ratings of presidents as measured by opinion polls from Truman to Clinton. She found their arcs so similar she was able to create a generic graph illustrating what she called “the decay curve.”

Presidential popularity starts out at an impressive level — usually in the 60 to 70 percent approval range — and proceeds steadily downward, reaching bottom in the early months of year three and then gradually climbing again, although not to the initial level. “Second-term presidents start high again and fall in popularity even more sharply,” she concluded.

Love at First Write

It’s hard to know if it’s a cause or an effect, but press coverage of the president also tends to be more favorable early on. According to a 1981 study by Michael Baruch Grossman and Martha Joynt Kumar of Towson University, there is more — and more positive — coverage of the president during the inaugural year of an administration than in the remaining three years. They suggest this is due to several factors, including the inherent newsworthiness of a new president’s policy proposals and the fact that reporters must rely more on official statements and briefings early in a term because they haven’t had time to develop confidential sources within the administration.

A more recent study of new presidents and the press doesn’t dispute that conclusion, but it suggests different dynamics are also in play. The Project for Excellence in Journalism compared media coverage of the first 100 days of the Bill Clinton and George W. Bush administrations. Examining stories and opinion pieces on four major television networks, The New York Times, The Washington Post and Newsweek magazine, it found that 22 percent of Bush’s coverage was positive, 28 percent negative and 49 percent neutral, compared with Clinton’s 27 percent positive, 28 percent negative and 44 percent neutral. (In each case, 1 percent of coverage was labeled “satirical.”)

What is perhaps most interesting about this analysis is the finding that early coverage of both men was heavily influenced by the conventional wisdom that came to be accepted during the campaign. “After expressing clear doubts about Bush’s intelligence and competence during the 2000 campaign, the press gave the new president high marks when the administration managed a smooth transition, particularly during the cabinet appointment process,” the report states. “Clinton, in contrast, was hammered in his early days for missteps over gays in the military and botched appointments, which were all the more surprising for a candidate depicted as one of the most skillful politicians in generations.”

In other words, expectations matter. The bar was set low for Bush, and he cleared it, leading to more positive coverage in his first month than Clinton received in his. But their positions reversed in the second month, primarily because Clinton’s policy proposals were seen as more popular than Bush’s. The pattern is clear: Press coverage of the new president “starts by focusing on whether the man is up to the job,” the report concludes. “Then policy takes over.”

Wooing Congress

So have newly elected presidents succeeded in parlaying their popularity into legislative victories? The evidence is decidedly mixed.

In a 2005 study published in the journal Congress and the Presidency, Casey Byrne Knudsen Dominguez of the University of San Diego concluded that presidents “have higher success rates during the first hundred days of their first year than they do later during their first year or during the first hundred days of non-inaugural years.”

Dominguez came to this conclusion by focusing on a “presidential success score,” which measures the percentage of congressional votes on which the president’s publicly stated position prevails. Looking at presidents from Kennedy through Clinton, he found chief executives have, on average, an 88 percent legislative success rate during the first 100 days, compared with 78 percent in the second hundred days and 74 percent in the third. The rate for non-inaugural years is only 65 percent.

This honeymoon effect “does not bestow advantages uniformly on all presidents,” Dominguez wrote. “In fact, it only seems to confer significant advantages to a president in his dealings with a House or Senate that is controlled by the opposing party. In their dealings with Houses and Senates controlled by their own party, the first 100 days … are no different from similar periods in subsequent years.”

A group of Loyola University Chicago political scientists led by John Frendreis came to a different conclusion in a 2001 paper published in Political Research Quarterly. Looking back much further in history — they included data from 1897 to 1995 — they compared the legislative output of Congress during the first 100 days of a presidency to the first 100 days after midterm elections. (They did not differentiate between legislation the president supported and bills he opposed.)

They found that the amount of rapidly enacted legislation has declined dramatically over the years, probably because the proliferation of congressional subcommittees means a bill has to go through more scrutiny before getting to the floor now than in the past. But with a couple of exceptions, the difference in legislation passed between the inaugural and midterm first 100 days was quite small.

Two factors do help a new president get bills passed quickly, according to this study: “(1) adverse economic conditions, and (2) greater electoral support for congressional candidates of the president’s party.” That second conclusion, of course, directly contradicts Dominguez’s findings that the “honeymoon effect” is greater during a divided Congress and suggests that, as with matrimony, the success of political honeymoons may depend as much on the personalities of the partners as on the amount of time they’ve been united.

Sign up for our free e-newsletter.

Are you on Facebook? Become our fan.