In 2000, Ben Katchor made history by becoming the first cartoonist to win a MacArthur Fellowship. By that point, he had already won various prestigious awards, like a Guggenheim Fellowship, and had been the subject of profiles by writers such as Lawrence Weschler and John Crowley. His work would continue to appear in highbrow magazines and get reprinted in book form by major publishers, he’s an associate professor of Illustration at the New School, and, at the time of my interview with him, he had just finished editing The Best American Comics 2017.

At the end of such a successful life, Katchor ought to be happy, right?

“I feel like we’re replaying World War I, with the Espionage Act being revived and journalists being threatened for merely doing their jobs,” he tells me. “And on top of that, the ecosystem is collapsing. It’s a nightmare, quite honestly. It would be one thing to have a dictator in power … but unbreathable air on an overheated planet? There’s no escape.”

This was not the Ben Katchor I had expected to interview. I had first encountered Katchor’s work in college, digging through the comics section in the stacks before finding, and then devouring, three Julius Knipl collections that were available in 2000. In those stories, I discovered a world both alien and familiar. Although I had grown up in an isolated rural community, I found something comforting about Katchor’s lumpy-bodied characters and their running commentary on the ephemera of a surreal, ever-evolving urban landscape: distant melodies from frozen custard trucks first heard decades earlier, the front page of a Socialist workers’ newspaper speared by the trash-gathering stick of a park attendant. As a budding historian, I was captivated by this powerful evocation of an imaginary past.

To a certain extent, my understanding of this work was shaped by commentaries like Michael Chabon’s introduction to Katchor’s 1996 comic strip collection Julius Knipl, Real Estate Photographer: Stories. Chabon extolled Katchor’s vision of “the impossible beauty and profundity … of a city of men living alone in small apartments, tormented by memories.” Chabon, in turn, had discovered Katchor via “A Wanderer in the Perfect City,” Lawrence Weschler’s New Yorker feature about the artist. Neither version seemed like the portrait of a political radical.

“My father was the one who took me to S.D.S. headquarters,” Katchor told Weschler in 1993. “He was so political that he used up all the space for politics in the family—so that the ’60s kind of passed me by. I was buried in comics.”

When I mention that quote to Katchor, he corrects me.

(Photo: Mike Minehan)

“That discussion centered on Julius Knipl, the character I drew in many of those comic strips. … Knipl, you see, was an observer who never got involved, who merely commented on what he saw,” Katchor says. “But for me, leftist politics was the home base, and I always looked at this world as something to be critiqued, even if that critique arose from a different place than my father’s did. … I wound up offering this critique as a cartoonist, not as an analyst or politician.”

Katchor’s earliest strips appeared in comics anthologies such as Raw and various alt-weeklies. Over time, his readership expanded, and his signature character, the “real estate photographer” Julius Knipl, began appearing in strips that ran in the Washington City Paper and the New York Press. From there, his illustrations moved into higher-paying legacy publications like The New Yorker, and his first full-length graphic novel, The Jew of New York, was published by Pantheon in 2000, the same year he won his MacArthur Fellowship.

“The Jew of New York, which came out that same year in book form, was an important work for me,” Katchor says. “It’s a very political story, and though it is not based on some deep reading of historical sources, as a professional historian might do, it evokes the spirit of the beginning of the market economy in 19th-century America. There is a great deal of political critique and content in there: con artists, hucksters, delusional religious seekers, the strange nationalistic impulses of a Jewish politician.”

From there, Katchor explains, the political themes of his strips became more overt. “Have you read [the 2013 book] Hand-Drying in America? That collection is extremely political,” he says. “There are concepts raised in there—lawsuits, ecological disaster, the nature of capitalism. …. It’s not on the nose, because I’m not drawing caricatures of real-life politicians or doing obvious parodies of things, but those themes are front and center nevertheless.”

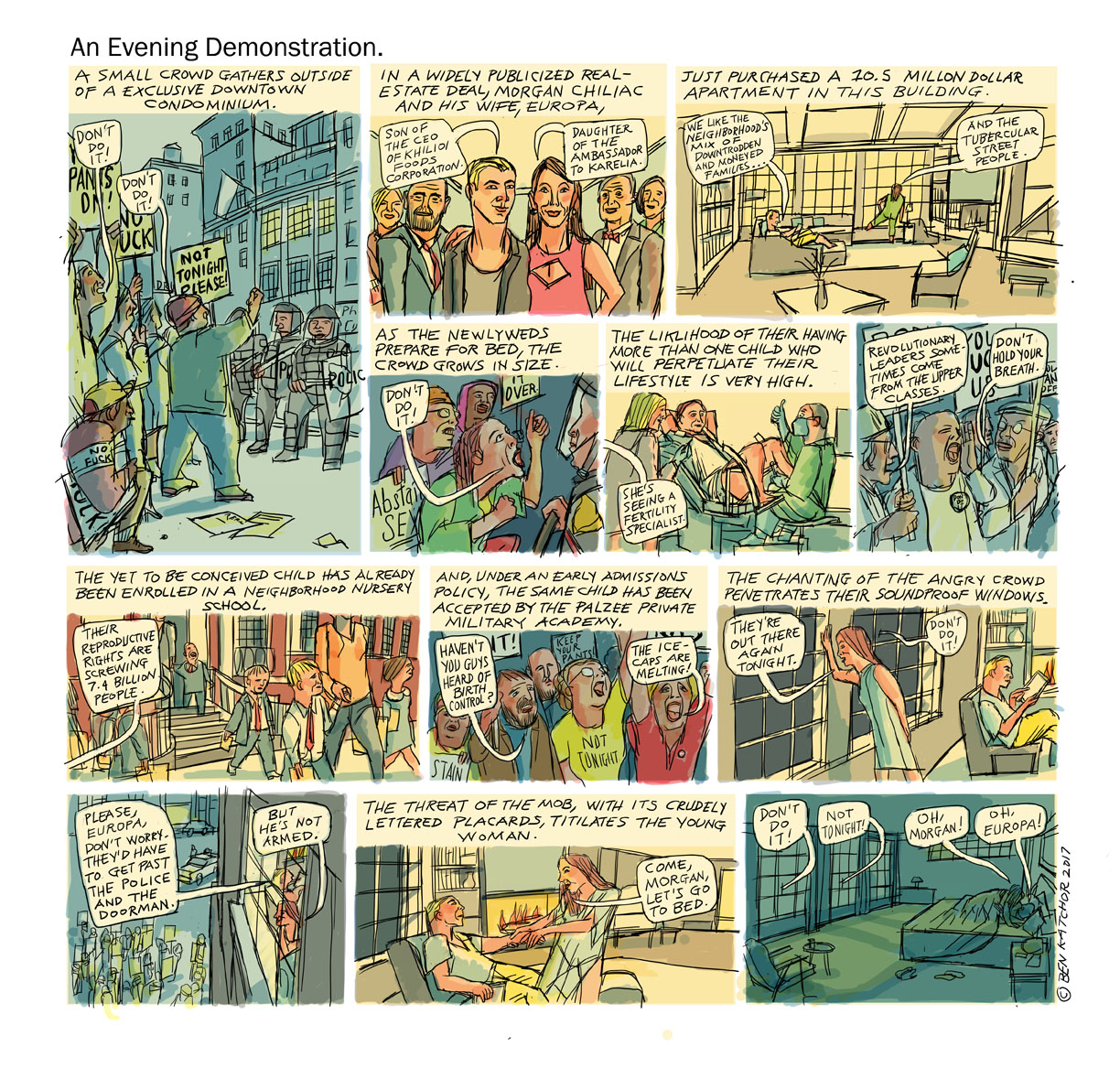

Katchor’s latest comic illustration project, Our Mental Age, further elaborates these ideas. In the three currently available strips, a wedding party is wiped out by drone strikes, activists protest the possibility that two rich people might reproduce, and a con man approaches impoverished parents seeking payouts in order to keep the juvenile delinquency of their children a secret.

(Photo: Ben Katchor)

“This is a crazy time, a mental age. You look at our politics and … well, I was shocked that Hillary [Clinton] was the best opponent that could be found to run against [Donald] Trump,” Katchor says. “It’s obviously a business, a racket, and it’s controlled entirely by businessmen. How can you fail to address that in your art, even if only obliquely?”

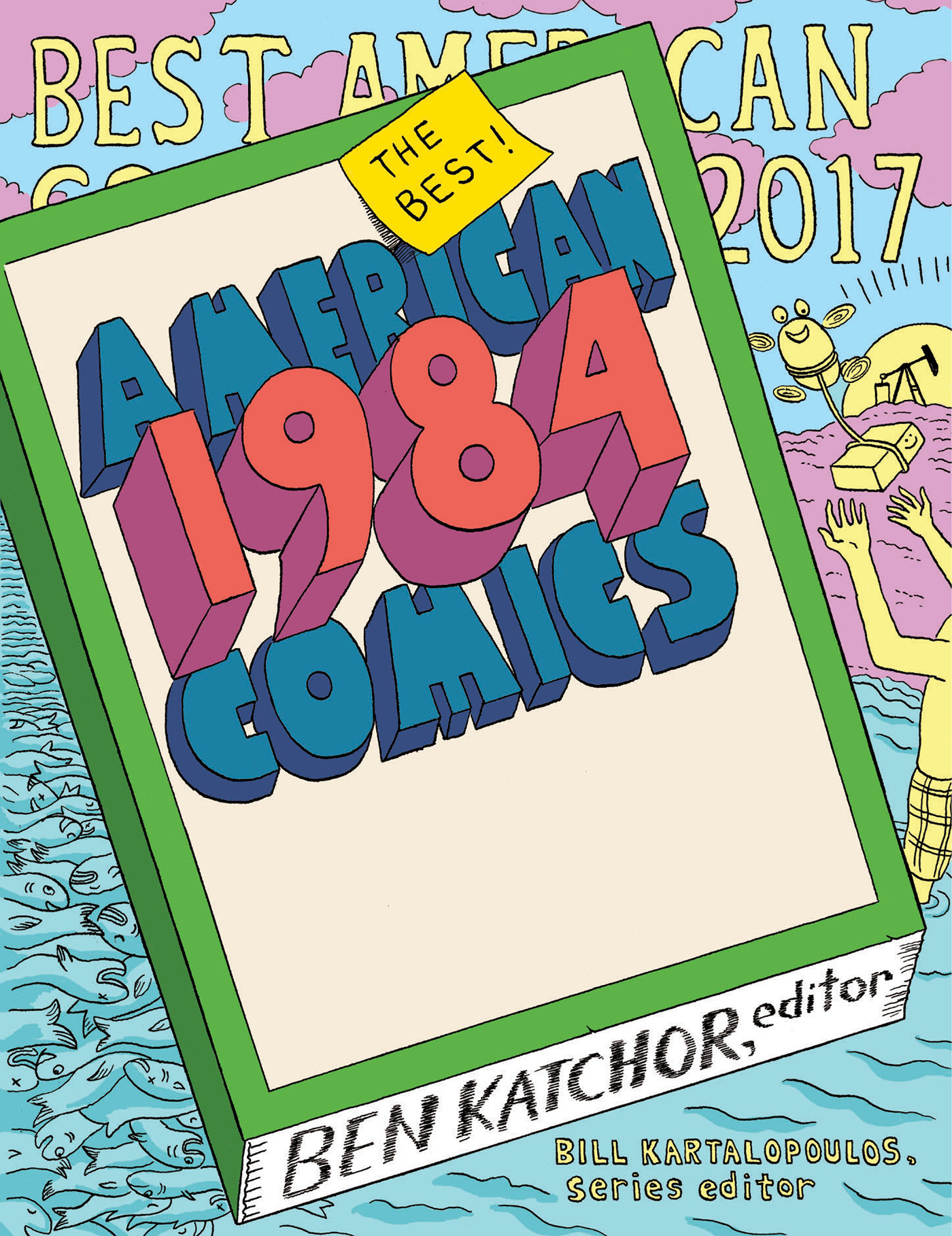

The cover of The Best American Comics 2017, drawn by Matthew Thurber, is itself a political provocation of the highest order: a stylized reproduction of the well-known cover art for George Orwell’s novel 1984 that is political in a way that the previous five covers—each aesthetically evocative but context-free—were not. Katchor’s bitterly humorous introductory text, which skewers the pretensions of himself and other comic artists in this era of increasing economic precarity, catalogues the impulses that might compel a “cartoonist to toil in obscurity, and with little remuneration over decades, often through the prime years of their life.”

“To be a cartoonist now, in this world, with the costs it imposes on you? Well, it certainly isn’t easy, because this is as bad as I can recall things having been,” he says. “When I was developing my interest in cartoon art, I was enrolled in college studying painting and literature. But I loved this idea of the mass reproduction of artwork that could live on a rack near a candy stand, and I didn’t have nearly that same passion for the world of galleries and high modernist art. And fortunately, when I started working on these projects, the old New York City in which I lived was so astonishingly cheap. Rent, in my case, amounted to $200 a month, and if I sold a strip a week for somewhere between $25 and $100, I could squeeze by. This way of working was possible then.”

(Photo: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt)

Katchor does, however, take some measure of hope in the many promising samples of comic art he was asked to evaluate when editing The Best American Comics. “There’s been an explosion of work done in this form, a broader sense of what it can be used to accomplish, unlike the superheated market for so-called ‘serious’ art, and here you have all these talented creators trying to solve the problem of the comic strip,” he says. “In the 1970s, it was difficult to publish such things because the literary world, the art world … the people there were extremely suspicious of comics. I had been been afforded a middle-class lifestyle by my parents, and yet I was seeking out a career in a field that amounted to the bottom of the barrel, the lowest level of pulp fiction.”

Katchor’s forthcoming book with Schocken, The Dairy Restaurant, will examine aspects of Jewish dietary history in graphic novel format. “Food has its own place in how we create and critique culture, which I’ve already explored in other strips,” he says. “But this goes back to my point about how the comics medium is mature enough that not just me but many others can tackle all kinds of subjects … and even so, we’ve yet to tackle all the ways that comics production can democratize the image. It’s still not quite what I envisioned in my wildest dreams: racks next to candy stands filled with lots of diverse, intellectually compelling comics work, available at cheap, pulp-level prices to anyone seeking good art.”

With all of that in mind, I ask Katchor whether he would still pursue a career in comics, were he a college student today.

“On the one hand, that’s a question I can’t really answer,” he replies. “If I were a college student today, that would mean my parents would have been born, at the earliest, in the 1950s or 1960s, rather than in, say, Warsaw, Poland, in the late 19th century. If I were starting out now, I’d be a completely different person, having grown up in a completely different world, been exposed to different technology, different art and animation … things that weren’t possible when I actually did grow up.”

He pauses a moment. “But you know, if I were to answer your question, knowing what I know about the world we live in, about the environmental harm we’ve caused to the planet, I would probably have dropped out of school and devoted my time to blowing up oil pipelines. Yes, that’s something I probably would have done.”