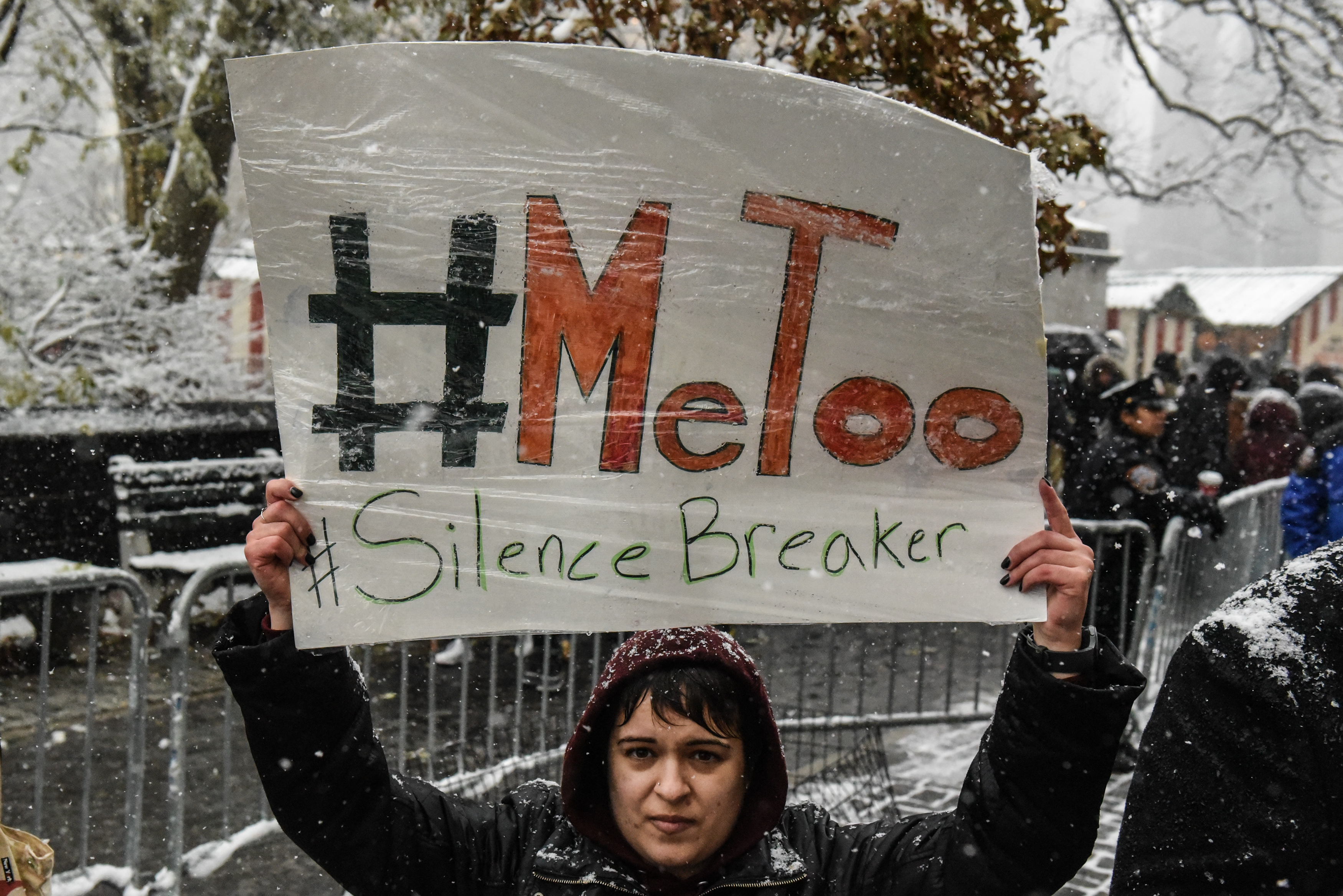

(Photo: Mark Ralston/AFP/Getty Images)

In the final two weeks of October, amid accusations against powerful men like Harvey Weinstein, Brett Ratner, and Kevin Spacey, tens of thousands of individuals took to social media to share their own encounters, experiences, and trauma. As stories were shared under the “#MeToo” umbrella, a decade-old hashtag saw renewed life and quickly became a rallying cry for those who’d previously remained silent—in some cases for decades—in their stories of sexual harassment or assault. The movement quickly gained power; months later, “The Silence Breakers” became Time magazine’s “Person of the Year.” (It should be noted, though, that the Time cover did not feature Tarana Burke, the black woman who created the original slogan; it did feature Taylor Swift.)

The movement has grown far beyond a hashtag, signaling a much broader cultural shift in ideology based in healing, accountability, and a rooting out of the bad actors. There are local news segments about talking to your child about harassment, senate bills, and statements from legacy organizations strengthening their commitment to the creation of safe workplaces and classrooms. With resignations from congressmen including John Conyers and Al Franken—contrasted with the stubborn refusal to step aside from those like Roy Moore and President Donald Trump—the cause has galvanized many around the need for concrete action.

For those who work in victim advocacy, the #MeToo movement has caused an explosion of activity around the work to which they’ve already dedicated their lives. Advocates are seeing a wider range of clientele calling in than before; in addition to those looking for imminent advice, survivors, partners, and even friends and family have been seeking aid from advocates. The work they’re doing is reaching a broader audience than ever, but with it comes the pressure of being an impartial place for aid, as the movement races forward. It also means keeping a closer eye on their own mental health as they take up the cause.

According to the King County Sexual Assault Resource Center, which has operated in the Seattle area since the 1970s, calls to its 24-hour resource hotline have increased by more than 44 percent since last year. Call are coming from those who wish to disclose their own abuse, as well as those who have recently learned that a friend or partner was abused, possibly through a Facebook status. The added attention has also driven financial support; KCSARC reported recently that at least one gift came in with a note referencing the hashtag. It read: “[You helped two of my friends … that I know of.”

This is part of a larger pattern. When Taylor Swift went to court for sexual assault in August, the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network reported an increase in calls. The year before, when Donald Trump’s Access Hollywood tape leaked, it noted a 33 percent increase in just one weekend.

KSCARC’s executive director, Mary Ellen Stone, said in one interview that she’s “never seen anything like” the #MeToo campaign and conversations its sparked. It’s a sentiment KCSARC resource line manager Laura Lurry agrees with.

“The increase of media involvement [means] people see our services and our number out there more,” says Lurry, who has worked at the hotline for more than 20 years. She says that the media’s largely empathetic coverage to survivors has helped as well, by making disclosure “more acceptable” and placing an emphasis on ending further perpetration. Media outlets have also become more accustomed to including resources within stories about sexual assault and harassment, which means there is not only coverage of the events, but advice about the options that exist for survivors.

Hotline calls tend to pick up during waves of disclosure for a few reasons. In addition to the publicity these resources receive, media arcs about sexual assault and abuse can bring up emotions in those who have no other outlet—or didn’t even realize these avenues exist for all. Calls have come in from those who are having a difficult time processing the onslaught in the news, those who feel like they should be speaking out but can’t, and those who have not been victimized themselves and are wondering what they can do to help.

#MeToo’s emphasis on speaking out publicly can also create discomfort for survivors who feel like they can’t come forward for a variety of reasons. Though “breaking the silence” has been lauded by Time and other publications, remaining silent often feels like a protection mechanism for survivors—and survivors’ inability to speak out can double the guilt or shame they may be experiencing, leaving them feeling somehow less worthy of a sympathetic ear if they don’t choose to be very public with their pain. For them, hotlines are an invaluable resource. And for hotline workers, their stories are especially essential. Lurry says that, in those situations, she and her staff are “humbled” to be able to take the call.

Though the professionals answering the phones at hotlines like KCSARC’s do speak predominantly to survivors, Lurry says many of the calls that KCSARC receives are not from those who have been victims of assault, but, instead, from those who know and love someone who has been a victim.

Those who may have just learned that they know a survivor—or that they have been a perpetrator—are also calling the hotline.

Often, and especially now, men are calling without being sure of what they want to say: “My girlfriend recently told me she was assaulted and I don’t know how to help”; “I just learned my daughter was raped at college”; “I think I may have crossed the line with someone.”

For those calls, Lurry says her role is less about talking and more about asking questions: “How is this also impacting you? How can you support the loved one in your life and yourself?”

KSCARC also works to educate people about consent. This includes providing shifts in language—toward victim-centered phrasing, for example—and tools, including websites, articles, and KCSARC’s own blog. Some of those articles have been written in light of the #MeToo movement; local news outlets have been reaching out to sexual assault resource centers around the country to ask for tips and tools not just for those who have been both directly and indirectly affected.

(Photo: Stephanie Keith/Getty Images)

Lurry says that education is critical—by examining the ripple effect that harassment and assault have to help those who have not been victimized “understand the impact.”

Of course, there are people on the other end of the line—and they, too, can feel the weight. Individuals who work in sexual assault advocacy and research are feeling the increase, both in calls and in media attention. It’s inescapable, and it can be potentially exhausting.

“You have to have that balance,” Lurry says, adding that she and her staff work to make separate space for their personal lives. The attention has also given her a renewed sense of purpose; she says that, recently, she’s “found an inner sort of energy.”

That may not be the case for everyone working on the front lines of this work though. “Vicarious trauma” is a known issue among those who work directly with survivors—not just of sexual assault, but also of those in other traumatic environments. Different from burnout, which can occur over time, the American Counseling Association defines vicarious trauma as “a state of tension and preoccupation of the stories/trauma experiences described by clients.” The symptoms of vicarious trauma can look a lot like those experiences by primary trauma survivors—anger, jumpiness, and diminished joy.

Research on the impact of doing this kind of work—as Lurry has been for more than 20 years—isn’t copious, but there is some, and much of it echoes Lurry’s experience. In 2011, a study found that “good soldiering,” or the perception that a person is working toward a common good outcome, can help reduce burnout. More recently, a study that looked specifically at those who work as sexual assault advocates found that, when they felt supported thoroughly in the workplace, they were overall satisfied with the positive impact of their workplace.

But vicarious trauma does exist—and it can often co-occur with the satisfaction that workers experience. A frequently cited 2006 study found that half of social workers developed a “high” or “very high” level of “compassion fatigue.” These social workers demonstrated symptoms including exhaustion, depersonalization, irritability, and sleep difficulties.

The risk of vicarious trauma can increase significantly with increased demand, attention, or workplace stress. It can also increase if a person feels that they can’t escape the subject matter—like, for example, if their daily work is also the subject of wall-to-wall news coverage and the only thing their Facebook friends are talking about.

The Washington Coalition of Sexual Assault Programs has worked to help those in the field better recognize their own symptoms, advocating for changes like the promotion of self-care in the workplace.

“Working with child sexual abuse/assault victims can produce different trauma impacts that are not recognized until coping skills have eroded,” reads one fact sheet for providers. “We are forever changed by this work and must continue to be aware and to keep ourselves healthy.”

The people who do this work find ways to unwind. They go to football games and have ugly sweater parties. They go on staff retreats to discuss their feelings. And they speak openly about their experience in the line of work they do; KSCARC workers have been fielding more calls than ever, both from hotline users and media outlets looking to learn more and frame the discussion.

But when the phones are ringing off the hook, taking time away can be difficult; though KCSARC closed their offices for Thanksgiving and the following day, the hotline remained open, just as it does every single day. Because, though the media attention may fade and the perpetrators may lose their jobs, the fact of sexual assault remains—and so do hotlines, staffed with dedicated workers, ready to pick up the phone.