“Mental ward / is where I landed,” begins a poem by Marshun, an inmate at Cook County Jail in Chicago. The poem describes Marshun’s struggle with bipolar disorder, as well as his appreciation for flowers and photography. He was diagnosed before first entering Cook County Jail, where he’s been an inmate on and off since he was 20 years old, but it was only during his most recent stint at 33 that he entered the Mental Health Transition Center, a program that provides inmates with mental-health services. “If I had come to this program when I was 20,” Marshun says, “I wouldn’t have come back to jail.”

Marshun’s story is just one of many that photographer Lili Kobielski captures in her recent book, I Refuse for the Devil to Take My Soul, a revealing collection of portraits and interviews from inside Cook County Jail. The facility is not only one of the largest jails in the United States, but it may also be the nation’s largest mental health care provider.

Many inmates receive mental-health treatment at Cook County Jail simply because it is the provider of last resort. Beginning in 2009, the state government of Illinois crippled its health-care system, slashing nearly $114 million in funding from mental-health services and depriving 80,000 residents of access to mental-health care through budget impasses. As a result, two state-operated facilities and six city clinics closed, two-thirds of non-profit agencies in Illinois reduced or eliminated programs, and a third of Chicago’s mental-health organizations lowered the number of patients they served.

One way or another, many of those in need of mental-health services found themselves in Cook County Jail. Of the approximately 100,000 people who come in and out of the facility each year, a third struggle with mental illness, according to the Vera Institute of Justice, a non-profit organization dedicated to criminal justice reform.

While Cook County Jail is an extreme manifestation of the relationship between mental-health care and incarceration, it is otherwise not unique. A report by the Vera Institute describes how jails and prisons became the de facto mental health care providers nationwide: Throughout the 1960s and ’70s, a shift in mental-health care delivery occurred, with patients becoming deinstitutionalized, or released from involuntary confinement at psychiatric hospitals across the country. Advances in treatment methods, along with a movement for patients’ rights, sought to situate patients in their communities, rather than in isolation. Unfortunately, the support necessary to maintain community-based mental-health care was insufficient—especially following the Great Recession in the late 2000s, when state governments balanced their budgets by cutting funding for social services. Whereas half a million people with mental illness were held in psychiatric hospitals in the 1950s, the same number are now held in jails and prisons.

I Refuse for the Devil to Take My Soul tells the stories of these patients-turned-inmates. Through candid interviews and participatory portraits, Lili Kobielski offers both inmates and staff the opportunity to share their perspectives on how they as individuals, and the U.S. as a country, have gotten to this point—where one of the nation’s largest jails and one of its largest mental health care providers is one and the same. Pacific Standard recently spoke with Kobielski about the origin of her book, differing views on the source of incarceration, and poetry in prison.

Why were you first attracted to photographing inmates in general and those at Cook County Jail in particular?

This project started in the summer of 2015 when I received a call for pitches from Narratively. At the time, they were collaborating with a wonderful non-profit, the Vera Institute of Justice, to produce stories specifically about jail. I began researching jails across the country and was shocked when I came across some of the statistics on Cook County Jail. Not only is Cook County Jail the largest [single-site] jail in America—its population hovering around 8,000—it’s estimated that one-third of this population is mentally ill, making the jail one of, if not the largest mental health care providers in the U.S. With this project, I was especially interested in hearing and recording inmates’ stories, verbatim, and also exploring the systemic issues that often land people in jail.

Jails and prisons are notoriously opaque institutions. How were you able to gain access to Cook County Jail? Do you feel that you were in any way kept from seeing what “real life” is like in there?

I was collaborating with the Vera Institute of Justice throughout this project, and, without them, I doubt I would have gotten access. This particular jail is known for being more accessible and transparent than most, and while my first visits were quite controlled, I was given more freedom to photograph and interview people as time went on. From my experience there, the staff is genuinely trying to help people the best that they can.

There seems to be a divide between the perspectives of jail staff and inmates, both of whom you interview in your book. The staff identify the systemic failings of the criminal justice and mental health care systems, while inmates tend to describe their incarceration as a result of individual failings. Do you think more needs to be done to help inmates understand the systemic issues that have pushed them into such dire circumstances?

It’s interesting that you think that. Yes, the staff was generally very articulate about the failings of the criminal justice and mental health care systems—granted, most of the staff I interviewed are specialists in these fields. My feeling is that most of the inmates I spoke to are incredibly self-aware and have an innate understanding of some of these issues, especially the systemic failings in their neighborhoods—how poverty, trauma, violence, bad schools, and little investment in their neighborhoods from the powers that be often has a direct correlation to incarceration and recidivism. I also think a central tenet of many of the jail treatment programs emphasizes taking responsibility for one’s actions as an essential part of healing, empowerment, and community building. And yes, I do think it is important to highlight the particular systemic failings affecting most of these inmates, especially in conjunction with the emphasis placed on accepting personal responsibility.

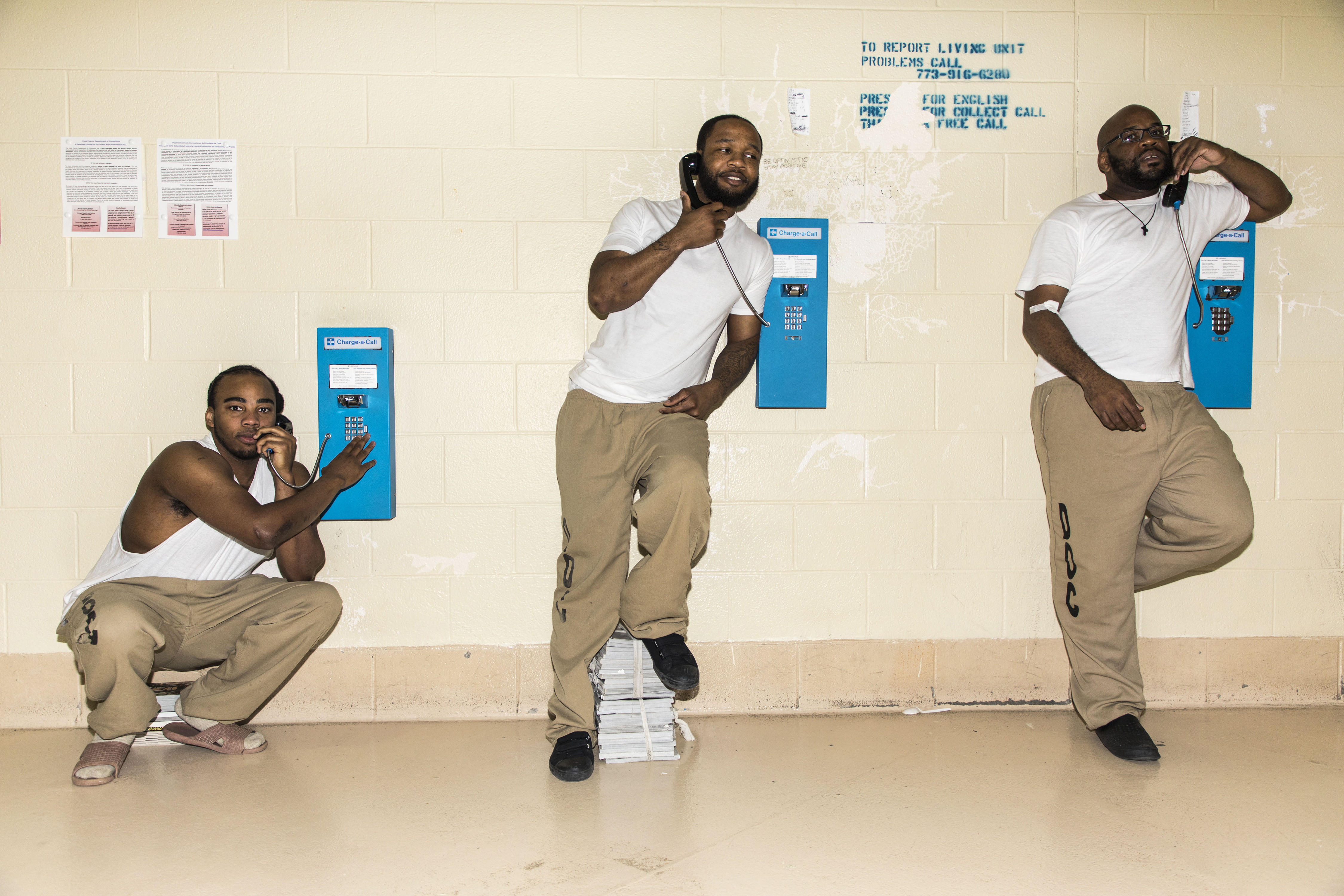

An interesting aspect of your portraits is the subject’s participation in its composition, with you asking them how, where, and with whom the photographs should be shot. Can you describe that process?

My hope is that this book is a storytelling platform for people who are rarely seen or heard, and it is essential to have the interviews be verbatim, first-hand accounts and for the portraits to be participatory. The process was simple. I always did the interviews first, so we could get to know each other a bit and develop a level of comfort. I then would ask if they’re OK having their picture taken, and if so, how they would like to be photographed. Some would choose a friend or friends to be photographed with, or a particular pose or location. For the most part, the photo sessions were fun and engaging.

One beautiful, though heart-wrenching aspect of your book is the copies of handwritten poems by an inmate, Marshun. In what context were these poems written?

Marshun is an amazing writer and poet. He mentioned in his interview that he was writing and had hopes of becoming a motivational speaker once he was released. I asked if he wanted to show me a couple of his works and he handed me dozens of beautiful letters and poems written during his time in jail. I brought them back to my hotel that night and read them all, made photocopies of them the next day, and gave him back his originals. I am grateful that he gave permission to include some of his incredible texts in the book.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.