(Photo: The U.S. Food and Drug Administration)

More than 30 years after Congress established new mandatory minimums for illegal drugs with the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, it seems America’s drug crisis has only gotten worse. A report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published last month showed that the rate of death from overdose over the last quarter of 2016 in the United States had exploded to 20.6 per 100,000 people, topping the previous record of 19.1 per 100,000 people seen during the preceding quarter, and a full 20 percent increase over the 16 per 100,000 overdose rate Americans experienced during the fourth quarter of 2015. And, according to government data, synthetic opioids (like fentanyl) surpassed legal prescription painkillers and illicit narcotics like heroin in 2016 as the primary source of drug overdose deaths.

The rise in opioid overdoses doesn’t just underscore the scourge of the American opioid epidemic, but also circumscribes a troubling trend in America’s current public health approach to controlled substances: According to new research published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, for the first time, the rate of opioid-related overdose deaths among non-Hispanic white Americans is comparable to the rate of cocaine-related overdose deaths among African Americans. But while opioid users have been met with government-funded policy initiatives, cocaine users are still often treated as anecdotal boogeymen by a White House that’s made law and order a major agenda point.

The public-health response to the opioid epidemic has proven a stark contrast to the stringent mandatory minimums that emerged from the law-and-order wave of the ’90s. The National Council of State Legislatures boasts that 40 states and D.C. have adopted “Good Samaritan” measures that offer immunity from arrest “when a person who is either experiencing an opiate-related overdose or observing one calls 911 for assistance or seeks medical attention.” There’s evidence that approach is working: One year after announcing that it would no longer arrest or charge opioid addicts, the police department of Gloucester, Massachusetts, reported that drug-related crimes dropped 27 percent while overdoses fell by 80 percent. Gloucester’s strategy is quickly becoming a model for other cities across the country.

It seems compassion, along with a healthy dose of suboxone, can help the ready and willing shrug off substance abuse. In New Hampshire—the epicenter of the modern opioid epidemic—a majority of local police chiefs reportedly agree that “medical professionals, not law enforcement, are in the best position to handle” drug addiction and overdoses, with law enforcement “unsuccessful in reducing the drug problem overall,” according to a survey conducted by Keene State College. In the intervening years, law enforcement agencies have banded together with their colleagues in neighboring Massachusetts communities (like Gloucester) to clamp down on traffickers without perpetuating a cycle of destitution and crime among addicts.

But the open arms approach isn’t just about treatment; it’s about stigma too. Groups, a network of opioid addiction clinics in five states that treats addicts through a combination of “community, fellowship, and buprenorphine,” found that it received “total engagement” from local lawmakers and police departments when it opened its first clinics in New Hampshire. “It was through repeated contact with patients and people who had just been labeled by society as ‘drug abusers’ or ‘people with a problem,'” Groups co-founder Jeff DeFlavio tells Pacific Standard. “But repeated contact in a community setting showed that so many of these addicts are completely normal people who had a series of less-than-ideal events unfold in their life that led to this. You recognize that there is absolutely nothing bad or wrong with these people. They just have a problem they’re seeking help for.”

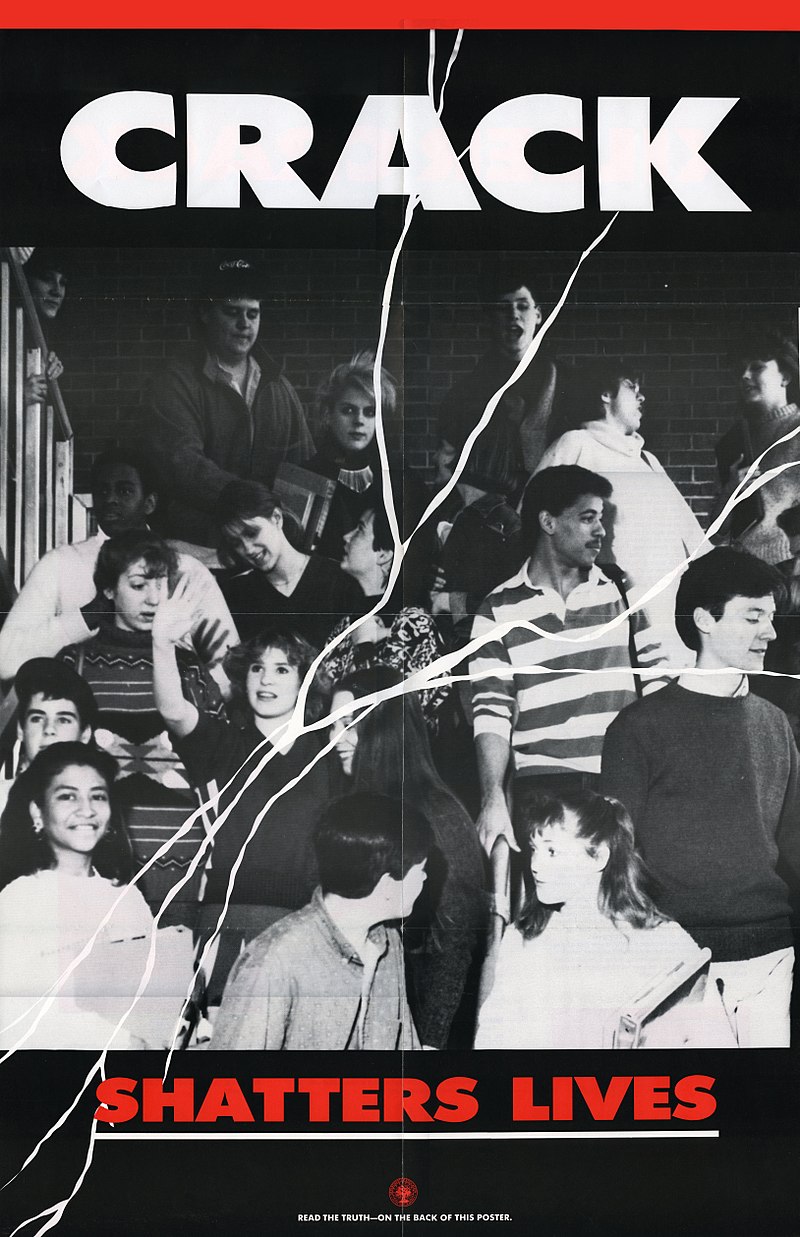

There was no such compassion for the victims of the crack cocaine epidemic that swept eastward from African-American neighborhoods in Los Angeles some 30 years ago. With America’s political focus on law and order centered on the crime wave of the 1980s, lawmakers in both parties pushed new crime legislation and “warned of super predators, young, faceless black men wearing bandannas and sagging jeans,” as Cardozo Law School professor Ekow Yankah told PBS Newshour last year. The disparity between the penalties for crack and powder cocaine established by mandatory minimums ended up sending hundreds of thousands of poor, young African-American men to prison for non-violent drug offenses while white, powder-huffing suburbanites retreated back to the comforts of their homes.

Since the Rockefeller drug laws of the 1970s initiated the legislative genesis of mandatory minimums, the U.S. government has spent almost a half-century criminalizing an entire subset of the population—and, despite the lessons learned in modern opioid treatment, the federal approach to drug abuse reflects those tired racial elements. In May, Attorney General Jeff Sessions directed federal prosecutors to “charge and pursue the most serious, readily provable offense” in drug cases—in other words, low-level drug offenses, like marijuana. (Sessions also helped nix a 2016 bill to ease sentencing for pot on the federal level, according to the Los Angeles Times.) And while President Donald Trump did manage to declare the opioid epidemic a national emergency in late October, the president isn’t as hot on tackling that particular drug issue as Sessions is on “street” drugs like marijuana and cocaine. The law-and-order mantra that catapulted Trump to the presidency is built on the coded racial logic of 30-year-old drug laws; it isn’t just visibly unjust, but measurably ineffective.

“I saw the war on drugs up close, and let me tell you, the war on drugs was an abject failure,” Senator Kamala Harris (D-California) said in response to Sessions’ mandatory minimum rallying cry in May. “It offered taxpayers a bad return on investment, it was bad for public safety, it was bad for budgets and our economy, and it was bad for people of color and those struggling to make ends meet.”

With overdose rates for opioid-addicted whites and cocaine-addicted African Americans now at comparable rates, policymakers are faced with a chance to re-examine the social and cultural contours of U.S. drug policy. Whether an administration built on law and order chooses to actually do something about it is another matter entirely.