(Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Some years back, Angie Lalabalavu’s grandson dipped a fishing net into a hidden pool he discovered in the stretch of shoreline in front of her house on Fiji’s Viti Levu island, right where the Sigatoka River meets the Pacific Ocean. When he pulled it out, the net was crawling with hundreds of mud crabs. They picked out the very biggest and threw the rest back, and the family frequently harvested dinners from the pool.

Now the pool is gone, and the crabs with it, and Lalabalavu doesn’t think they’ll ever come back.”This place was full of fish, crabs, and prawns,” the 60-year-old says, gesturing to the break in the tree line. In earlier years, she would sit on a wooden bench beneath an arch of branches, where she would watch the waves meet the river’s mouth across a vast swath of sandy beach; now the grass of her lawn drops steeply down to a swampy area. “Everything has disappeared,” she says.

Click here for more on Fijians’ everyday climate struggles.

Six months ago, a company called China Railway First Group began dredging at the mouth of the Sigatoka River, pulling silt and sand up from its shallow bottom and dumping it along the eastern bank in front of Lalabalavu’s home. The crab-stocked pool her grandson discovered was buried by the project, and the sandy shoreline in front of her home was replaced with mud. The area is now largely devoid of life, save for the mosquitoes and sandflies that gravitate to the still waters and now torment her family like never before.

By the time the Sigatoka River Dredging Project is done, China Railway will have pulled over 1.2 million cubic meters of silt from the river bottom between its mouth and the Sigatoka Bridge, just over two miles upstream—all in the name of flood prevention. But development along the Sigatoka River won’t end there.

Dome Gold Mines, an Australian mining company, has an exploration license to mine the river mouth for sand laced with magnetite—a source of iron. If the company ultimately receives a full permit to begin dredge-mining in the region, they’ll pull even more material from the bottom of the river and its banks, and from sand deposits on Koroua Island, a tract of incredibly valuable agricultural land for the village of Vunavutu.

The company has promised that the dredge-mining will both create jobs and further help to prevent flooding. Framed as a win-win, support for the projects was initially very high. It’s a scenario that’s all too common around the world: Questionable projects are sold to locals through a mix of misinformation and foreign investment.

But now, the indigenous communities, known in Fiji as the I-Taukei, don’t want either the dredging or the mining projects to move forward. Their connection to the land and their desire to protect it, they say, is far more important than any potential income mining might bring to the communities, and they no longer believe that dredging alone will prevent future floods.

“People have to remember, the river has always flooded,” says Tristen Pearce, a geographer at Australia’s University of the Sunshine Coast, and co-author of a recent report that looked at the human impact of development on the Sigatoka River. “That’s why it’s such fertile land.” Some 80 percent of Fiji’s vegetables are produced within the fertile river valley, which is known as the “Salad Bowl” of Fiji. But thanks to climate change, flooding has been getting worse. Long bouts of heavy rain and the floods that have always followed are becoming both more frequent and more severe.

And dredging is one of Fiji’s top flood-mitigation strategies, according to Inia Seruiratu, Fiji’s minister for Agriculture, Rural & Maritime Development, and National Disaster Management. “Over the years, [dredging] has proved to be a sound investment in disaster mitigation through the reduction in impact of flooding in the low lying areas of Fiji,” he wrote in February of 2017.

The initial Environmental Impact Assessment, which was finalized in 2012, stated that dredging would benefit the communities along the river by reducing flooding, and that any impacts to the river or the marine life inside it would be “minimal or temporary in nature.” According to community surveys conducted as part of the EIA, support for the dredging project was “overwhelming.” But today, many members of the indigenous community say that they were not properly consulted at best, and purposefully misled at worst.

“When the dredging came, with the information we were given, we had to say yes,” says Lanieta Matavesi, the spirited 72-year-old head of the indigenous women’s association for the province of Nadroga-Navosa, where Sigatoka is located, which has some 10,000 members. “We were told, ‘This will help with all the flooding.'”

The trouble is, according to Pearce, the idea that dredging can solve flooding is false. Even if a river is widened and deepened through dredging, its capacity will never match that of its catchment—the land area where rain or meltwater collects and drains into the river. It’s like trying to squeeze a swimming pool’s worth of water into a bathtub; a slightly bigger bathtub still won’t hold it all. What dredging will do, Pearce says, is devastate the ecosystem that the indigenous communities in Sigatoka depend on for both subsistence and income.

“All the scientific literature has clearly documented the negative effects of dredging in a river estuary on the ecosystem as well as the ecosystem services,” Pearce says. “If you dredge an estuary, you’re looking at between 100 and 200 years before it recovers.”

If officials in Fiji were really concerned about mitigating future flooding in Sigatoka, they should be looking upriver, Pearce says. Poor land-management practices—like cultivating crops right up against the river bank—have increased the amount of sediment in its waters, which builds up at the river mouth and increases the risk of flooding. Indeed, a 2016 study found that, in Fiji, “green” flood management techniques such as replanting along rivers and in flood zones were more cost-effective in preventing flood damage than dredging.

Pearce and his colleagues interviewed 31 villagers from five villages and one settlement along the river. They found that the Sigatoka River was a critical source of diet staples like fish, crabs, and freshwater mussels for every single one of them. Over half of those surveyed had their primary agricultural land on Koroua Island.

(Photo: John Trif/Flickr)

Government officials have tried to assure the communities that the EIA shows that dredging will have no significant effects on the river ecosystems or marine life, but Matavesi says that the indigenous community members are not convinced that an EIA was even completed. “Even if they did it, we have not been shown,” she says.

And already Lalabalavu has seen the negative impacts that dredging can have on her family’s primary food source. “I put my net out here and not one fish, not even one crab stuck in the net,” she says. “They’re all gone, they were all sucked out.” Saltwater is creeping farther up the river now, driving out the freshwater clams that the villagers upriver have long harvested. The river mouth has always been a nursery for bull sharks, but tiger sharks have been spotted further up the river than ever before, Lalabalavu says; she won’t let her grandchildren into the water anymore because of them.

Pearce and his colleagues found that dredging threatens more than just food security. “What we see is that this river is a mosaic of human uses,” Pearce says. “We all knew that people were fishing and getting shellfish from it, but what I didn’t know was the spirituality that’s connected to the river.” There’s a pond on the eastern side of the river mouth, for example, where the water is always clear. This sacred site is called Wai Ni Kutu, and it’s where the spirits of those who have died stop to bath themselves before crossing over to the next world.

None of these threats were discussed with the community, according to Matavesi. “There was no consultation, there was no awareness,” Matavesi says. “They have to tell us why they’re doing dredging; what are the advantages and what are the disadvantages? But many times, when they come for mining or dredging, they just talk about the advantages, to them and to us.”

The damage that’s been done by the dredging so far, Pearce says, is small compared to the damage that could be done if dredge-mining begins in earnest. “There is still the opportunity to have an alternative future,” he says—as long as Fiji’s government fulfills its promise not to allow development at the expense of the environment.

Frank Bainimarama, Fiji’s prime minister and the current president of COP23, has repeatedly declared his country’s dedication to “green growth.”

“We do not believe that putting the health of our environment first in any way jeopardizes our development. On the contrary, maintaining the pristine quality of our natural surroundings is front and center of every development decision we make,” Bainimarama said at the Ocean’s Conference in June.

“[N]o development on land or at sea in Fiji takes place if there is any risk to the environment,” he went on. “It is a central tenet of our Green Growth Framework and national development plans. And we are very proud to have drawn this responsible line in the sand.”

In the Fiji pavilion at COP23 in Bonn, Germany, Pearce says that he marveled at a massive photo of the pristine Sigatoka River estuary, before the dredging began. “It could be stopped,” he says of the dredging and mining projects. “This could be an example where the rights of the indigenous people prevail … this could be the precedent setter.”

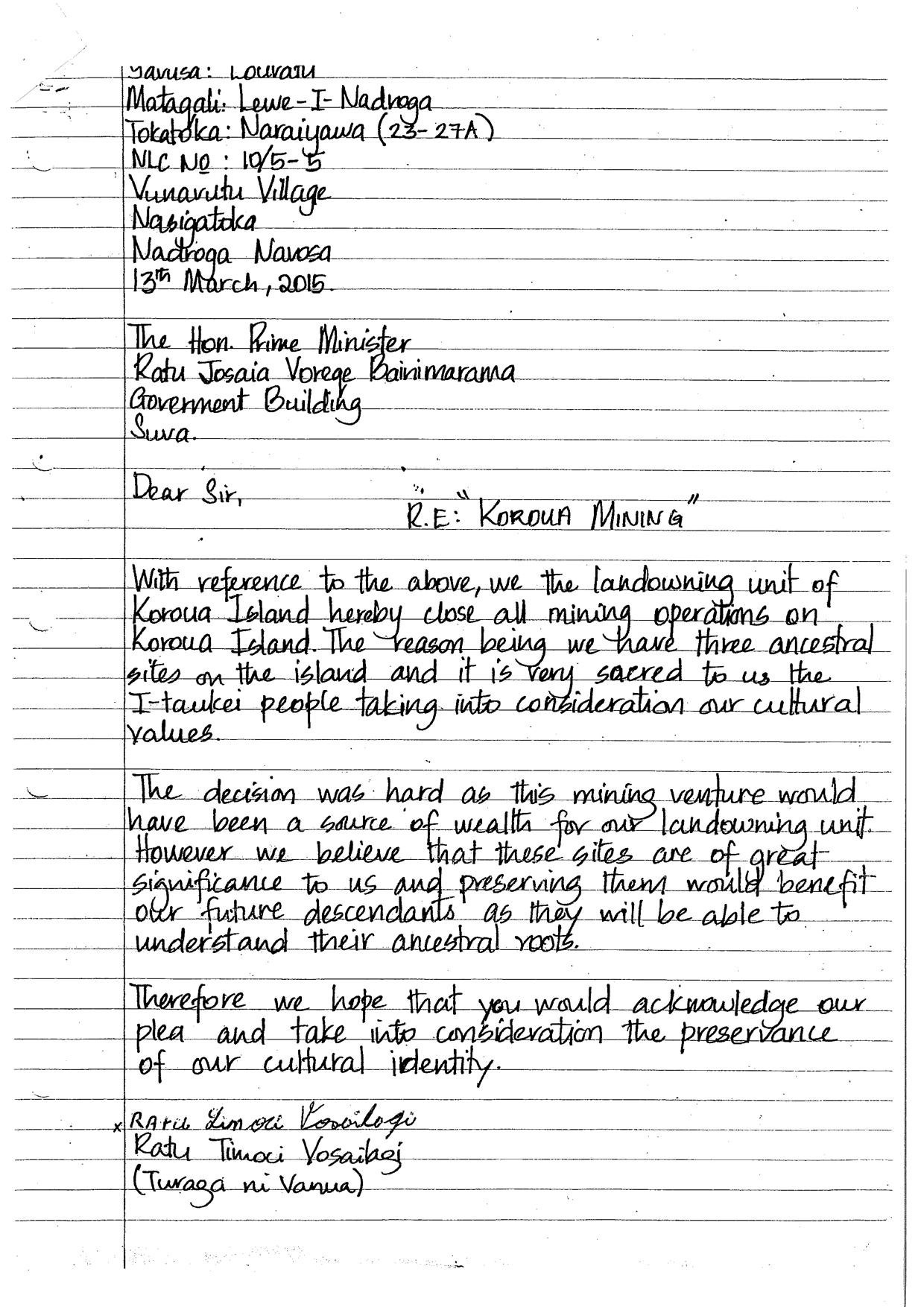

The village of Vunavutu, where Matavesi is from, has the rights to the land on Koroua Island, and the village has never consented to mining activities—exploratory or otherwise—on the island, which is home to three ancestral sites. They even sent a letter saying as much to Fiji’s prime minister. “We the landowning unit of Korea Island hereby close all mining operations on Koroua Island,” the letter begins. “The decision was hard as this mining venture would have been a source of wealth for our landowning unit. However we believe that these sites are of great significance to us and preserving them would benefit our future descendants as they will be able to understand their ancestral roots.”

All Matavesi is asking for now is that the government consult properly with the indigenous community before any more damage is done.

“When we met with everybody, they did not understand dredging, they were confused about what dredging meant,” Pearce says of his conversations with the community. “When they fully grasped what the outcomes would be, they unanimously said, ‘This cannot happen.'”

The exploration permit, Pearce says, snuck through “under the nose” of the indigenous community and their representatives in Fiji’s government. “But,” he says, “when that mining company files the full permit, they’ll feel the full power of I-Taukei. If it’s going to destroy the environment … it’s a no-go.”

Lalabalavu’s ancestors have lived on this land for millennia, and she has lived in this house overlooking the river mouth for all 60 years of her life. Her father built this modest home for her mother, who used to sleep on the beach right in front of it as a little girl. Her mother, now 87, runs a motel in a nearby town along Fiji’s Coral Coast.

“You know what she told me? ‘I will never come and see the river mouth like this,'” Lalabalavu says. Choking up, she pauses briefly, lifting a hand up to her mouth as she braces to continue. “‘I want to see it and recognize it as it was when I was born and grew up here.’ She is so brokenhearted.”