Less than two months after Donald Glover’s Atlanta won big at the 2017 Emmys award ceremony, a new report argues that the dearth of black showrunners at traditional networks and on streaming services is depriving television of black writers and, in turn, nuanced, atypical black characters and storylines.

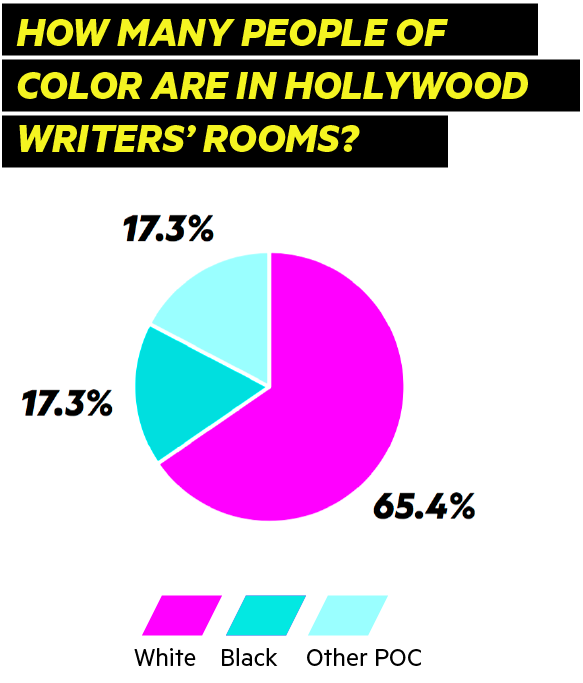

In the report, released Wednesday, author and University of California–Los Angeles sociology professor Darnell Hunt analyzed 1,678 episodes of 234 original, scripted comedy and drama series airing on 18 broadcast and cable networks and digital platforms during the 2016–17 television season. With data amassed from The Studio System, the Internet Movie Database, and Variety Insight, Hunt finds that, just last year, Hollywood writers’ rooms were only 4.8 percent black and 86.3 percent white, with 65.4 percent of writers’ rooms having no black writers. And that was all in the same year the Emmys nominated a record number of actors of color, from shows like This Is Us, Black-ish, and Atlanta.

“The outrageous level of exclusion in writers’ rooms has real-life consequences for Black people, people of color and women,” Rashad Robinson, the executive director of Color Of Change, the civil rights advocacy non-profit that commissioned the study, said in a statement on Wednesday. “While shows like Queen Sugar and Insecure boast diverse writers’ rooms and stand out as powerful examples of progress, the industry as a whole is failing.”

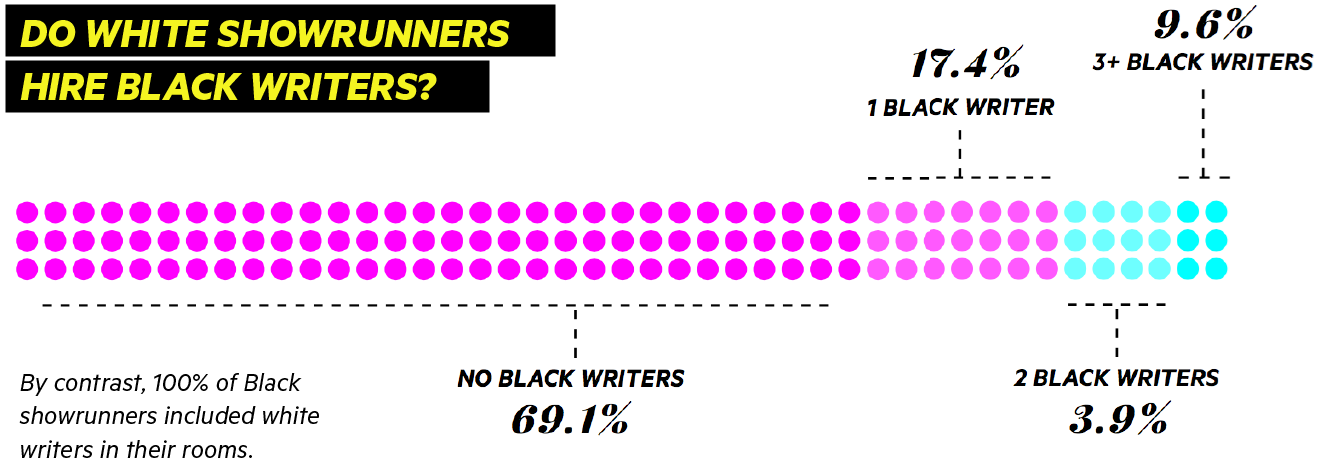

One reason for the lack of diversity, according to the report, is that only 5.1 percent of television showrunners in 2016–17 were black. White showrunners dominated television last season, accounting for 91 percent of the television shows studied. The majority of their writers’ rooms—69.1 percent—didn’t have any black writers at all, while 17.4 percent boasted just one black writer. Black showrunners, on the other hand, tended to hire several black writers: More than two-thirds—66.6 percent—had writers’ rooms with five or more black writers.

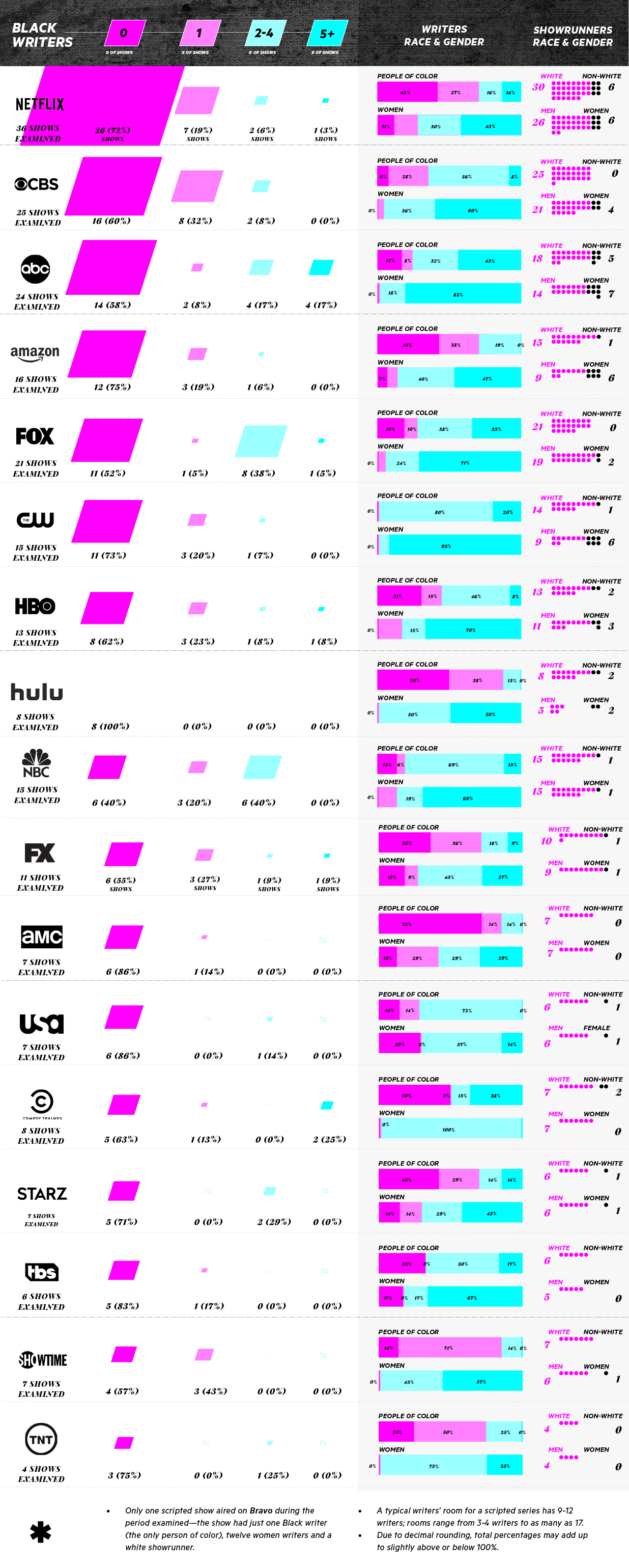

The report singled out networks and platforms with a bad recent track record on hiring black writers. AMC, Hulu, Showtime, and TBS were the worst offenders: Not a single show on these networks and platforms had more than one black writer. Though Fox, NBC, ABC, and Starz fared relatively better, they all still boasted a majority of shows with no more than one black writer: 57.1 percent, 60 percent, 66.6 percent, and 71.4 percent, respectively.

Netflix had the distinction of running the largest number of shows with no black writers at all last season: Twenty-six of the 36 shows studied. But it was still one of the only platforms that employed five or more black writers on at least one show, a list that also included ABC, Comedy Central, FX, HBO, and Fox.

Finally, Hunt looked at the network plot synopses for all episodes studied to see whether they confronted three key themes he deemed important to black viewers in the United States: black family “pathology”—the old, bigoted stereotype that black culture and identity has resulted in limited opportunities and segregation—the legitimacy of the criminal justice system, and the present significance of race and racism in America.

Of the four episodes taking black “pathology” as one of its subjects, the discussion was fairly nuanced: Three episodes identified structural factors as a reason for limited opportunities for black characters; two focused on mass media; and two identified that other groups had similar experiences. But of the 10 episodes that examined criminal justice, none showed that black people are often racially profiled and disproportionately harmed by the police; and of the 14 episodes that discussed racism in America, more than half did not mention racism lingers in the present day. Hunt singles out episodes of Atlanta, Marvel’s Luke Cage, and Insecure as airing thought-provoking episodes on these topics. All have black showrunners.

“Writers’ rooms with multiple Black voices, and/or a critical mass of writers of color, were found to be much more likely than those with no Black writers or only a tokenized Black writer to flesh out well rounded and realistic Black characters—people who inhabit story worlds ripe for thoughtful and subtle explorations of the very real role that race plays both in their lives and in society,” Hunt writes. “This was particularly true for writers’ rooms led by Black showrunners.”

Hunt argues that platforms and networks first need to make a concerted effort to hire more black showrunners; that television executives “cast the net more widely” when looking for pitches for new television shows; that white showrunners recognize the value in hiring more than one black writer to fill a “diversity slot”; and that networks and platforms green light diverse ensemble shows with writers’ rooms that aren’t afraid to confront politics in order to “circulate sensitive treatments of these topics and themes” to viewers.

Perhaps television executives looking to make a change in their line-ups could take Insecure‘s “Hella LA” episode from last season as an example of how black showrunners and writers respectfully treat real concerns for the black community. In the episode’s story, Lawrence (played by Jay Ellis) pulls an illegal U-turn in traffic when he sees a white driver in front of him do the same, but it’s Lawrence who is subsequently pulled over by a police officer. Clearly distressed, Lawrence changes the rap music in his car to classical music, puts his hand to the wheel, and speaks respectfully (if a bit anxiously) to the officer. The officer makes a joke of the situation, ribbing Lawrence that he should have arrested him because he has a Georgetown University sticker on his car, and the officer is a Vanderbilt University—Georgetown’s athletic rival—graduate. But the encounter colors the rest of Lawrence’s day, showing in one graceful bit of narrative how black people are disproportionately stopped by the police, and the anxiety they feel with the knowledge that they are also disproportionately shot by the cops. Insecure‘s a comedy—but in “Hella LA” it showed it could, and does, get serious about the topics that matter.