In April of 1873, during their first global tour, the Fisk Jubilee Singers were summoned to a smallish room in Buckingham Palace to perform a handful of spirituals for Queen Victoria. It was a landmark moment for the group, and the Queen readily requested certain tunes by name, including “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” “Did the Lord Deliver Daniel,” and “Go Down Moses.” Yet charmed as she was by the singers’ performance, it wasn’t the songs that struck her most forcibly. As Ella Sheppard, one of the group’s leaders, recorded in her diary, the Queen was transfixed by the singers’ variety of skin tones. “Tell the dark-skinned one to step forward,” the Queen is reported to have said to an attendant. Jennie Jackson, the singer in question, dutifully stepped forward, and Queen Victoria raised her eyeglass to inspect Jennie further.

The scene serves as an important set piece in Jubilee, the latest original work by playwright, director, and producer Tazewell Thompson, running through June 9th at the Arena Stage in Washington, D.C. Indeed, under the Olympian gaze of Queen Victoria, the audience comes to feel scrutinized as well.

Jubilee is Thompson’s song-driven celebration of the original Fisk Jubilee Singers. It offers a condensed biography of the group, beginning with its founding at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, where part of the grounds sat on a former slavers’ keep; early classes at the school scrounged funds by selling for scrap metal the various slaving instruments—chains, manacles, muzzles, iron masks, spiked neck collars—that they’d discovered in the earth. “Turning the instruments of our enslavement into the agencies of liberation,” as Sheppard puts it in Thompson’s script. The show follows the singers through their three major tours in the 1870s, as they broke some color barriers and encountered others that were less easily broken. Queen Victoria, for example, commissioned a painting of the group after they sang for her, but, as Thompson makes clear, the Queen was less interested in their artistic achievements than in their exotic appearance.

“That painting is now at Fisk University,” Thompson says. “[Queen Victoria] wanted to remember not their singing; she wanted the artist to capture the various shades of their skin.” Drawing from the singers’ accounts of that meeting, Thompson’s script gives the Queen a dazed, rhapsodic monologue about their appearance:

The faces. So unusual. The nose. Wide. Spacious. The lips. Thick. Full. Is that what affects the sound? The lips? Do they vibrate? The hair. Aggressive. Unapologetic. Wreathes and twists and locks that crown the head. Strands seem coarse. Yet civilized. Proud. Seated above. Like a tea cozy. No hat required. But. Ah. The colors of their skin. Some like tea with milk. Some the color of biscuits. Cinnamon. Tawny. Terra-cotta. Bronze. Russet. Rusty. Copper. My palomino horse. The bark of a tree.

This moment captures the bind in which the singers found themselves, even when they weren’t getting assaulted on the streets of America: Their performances commanded real musical admiration from some of the most powerful people in the world, advancing creative opportunities (not to mention worldwide representation) for freed black Americans—yet to some of their most august listeners, they remained a novelty suitable to be gawked at.

The group’s three tours between 1871 and 1878 earned over $150,000. Profits went to the university, establishing Fisk on a much more comfortable footing than when students had bought their first books with the proceeds from scrap metal. In today’s money, the Fisk Jubilee Singers’ touring haul would be worth around $3.5 million.

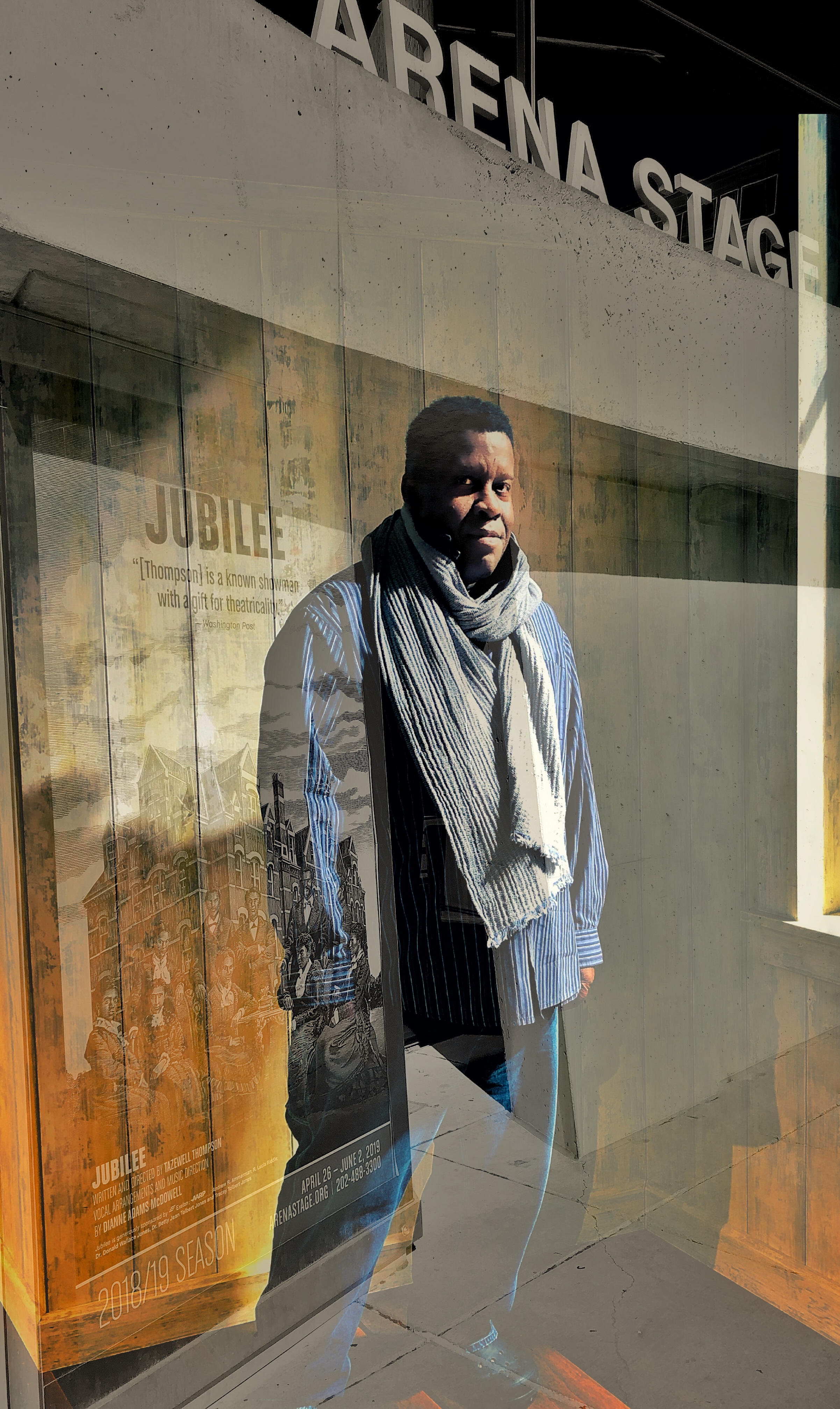

Besides being a playwright, Thompson has run several city theaters in the United States and directed plays and operas from Milan to Tokyo. (Full disclosure: Thompson gave me an acting job when I was eight, and we remain friendly.) Pacific Standard caught up with Thompson by phone to discuss his obsession with the Fisk Jubilee Singers, his childhood among nuns, and the work of transmuting trauma into art.

You’ve mentioned that spirituals were not part of you musical upbringing. Can you tell me a bit about how you came to spirituals after being raised by nuns?

(Photo: Fabian Obispo)

I grew up for almost eight years in St. Dominic’s convent, which is in Upstate New York, Rockland County; I was taken there by my parents, who I suppose on their own, without being married to each other, might have been upstanding parents, if they’d been married to someone else. And their togetherness brought about a terrible tragedy in my life. My brother was killed in a fire from their neglect that I was saved from, and I was sent to live in this convent. At first I couldn’t speak, I was so traumatized—I went from this tragedy to being in a place that was completely foreign. When I look back on it now, it was almost like a Dickens tale. But the convent was filled with wonderful women who had sacrificed [their] lives to take care of the lives of others: disturbed children or children from broken homes or homeless altogether.

My first year there, I received my baptism and confirmation and first communion; it was almost like I was on the path to become a priest or a saint or something. But as a child, what was wonderful about it was I was introduced to music there—not jazz or blues or negro spirituals, the music of my culture. Instead, I was introduced to opera. Sister Benvenuta would bring in these recordings every Tuesday and Thursday, recordings from the Longine Symphonette Society. So I learned how to read music, I learned Latin, but I never learned anything about negro spirituals. Not one lyric, not one note, nothing.

Just before I started high school, my grandmother came and took me, and I spent the next several years living with her out in St. Albans, Long Island. My grandmother was not a Catholic but a Baptist, and I would sometimes go to church with her on Sundays. I was very curious about her religion, and I went to her church, Calvary Baptist Church, and that’s where I first heard spirituals. It was the top-tens; “Swing Low,” “Wade in the Water.”

And what led you to write a play about these spirituals, and this group in this particular?

More than 20 years ago, I saw this PBS documentary on the Fisk Jubilee Singers. I had heard of them but didn’t really know too much about them. And my interest was piqued: I heard their story, about how they all came together from various backgrounds, some of them former slaves, and all of them magically, fatefully, having this gift of song—the ability to sing gloriously. And they all happened to end up one way or another at Fisk University, a school founded by abolitionists to bring the recently freed negroes together who were lost and confused and searching the roads.

By this point, [Fisk] was run down and always in danger of foreclosure, and this group of young men and women met and decided they needed to do something to save this school. They put their lives on the line constantly, went without food, froze in the winter, had a pathetic little vegetable garden, and no money at all—but they knew education was the path to real power and real freedom, for them and for future members of their race. And they toured to raise money.

At first, they didn’t want to sing these songs because they were associated with pain and suffering. While there was some hope, these songs came out of a yearning for freedom, came out of a great deal of torture and harm and neglect and being manacled and chained under slavery. But the songs were beautiful. And when they sang these songs, they found while passing the hat around to get money back to Fisk University, that it was these songs that these audiences were drawn to.

How did you go about researching this portrait of the original Fisk Jubilee Singers? Old books, microfiche?

I’m a research fanatic. I was curious about these songs. And the curiosity came out of my love of music from when I was six, seven years old under Sister Benvenuta, so I began collecting these [songs]. Long before there was eBay, I haunted stores and would see sheet music or a vinyl of negro spirituals and I would collect them. I have half a closet full of these materials.

The show gives us a fairly chilling idea of the violence these singers faced whenever they toured America.

Usually the places they stayed, they were thrown out once the proprietors saw they were negroes—not blackface, but actual negroes. On trains, they’d be asked to sit in the baggage car even though they had tickets to the passenger part of the train. And they were beaten up in certain towns. It was a very mean-spirited, very dangerous odyssey. I find them to be very courageous and heroic.

(Photo: Fabian Obispo)

Their white choral leader, George White, seems to have been a bit of a tyrant.

George White was a taskmaster, unrelenting; many suffered because of his overdiscipline. Ella Sheppard, for example, was always sick and always on the verge of losing her voice. And he would never let her or any of them take a rest or miss a performance.

Had they traded one master for another?

Yes. Ella Sheppard kept a diary, and that comes up in her writings and in the writings of Maggie Porter, and of Jennie Jackson, the most dark-skinned of the group. Ella admired White for his determination, and in the end realized that, without him being a white man, they couldn’t have gone into certain areas or certain hotels or get out of certain precarious circumstances. But she did voice that idea—that they’d traded one master for another. It was extraordinarily tough. They went through various illnesses of rheumatism and bronchitis and loss of their voices and pneumonia. And he never let up.

What is the source for that fascinating speech by Queen Victoria, about the singers’ skin tones?

The writing is all mine; I expanded on [period accounts]. When they were summoned to sing before Queen Victoria, she did request “Swing Low,” she did request “Steal Away,” but, more than that, she was fascinated by their skin color. Minnie was very, very light skinned, and then there were others who were brown or dark brown, or their features were a little more Caucasian but they had tawny-type skin, and others were blue-black. The Queen was astonished by that, but it was never expressed directly. Ella Sheppard wrote in her diary that [the Queen] would whisper to her attendant, “Tell them we are pleased with their singing, tell the dark-skinned one to step forward.” She lifted up her eyeglass so she could really inspect her [Jennie] and look at her skin. I don’t know her exact words, so I put it in my own words.

It’s a pointed choice not to have white actors play the white antagonists, and an effective one. Why did you go that direction?

I knew from the beginning I really wanted the focus to be on the Fisk Jubilee Singers and their journey and how they were brought together. I knew I didn’t want to introduce white characters because I would then want them to be whole and three-dimensional, and that would take up time and space.

I had to include their being confronted and beaten by a white mob. That they had this turning point in England with Queen Victoria. That they went to the homes of these Southern aristocrats, and sometimes they were not greeted with funds; they were given food, leftovers, as they waited on the back porch. I knew if I had some of the black actors portray the white characters, I thought that would actually be more powerful.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Pacific Standard’s Ideas section is your destination for idea-driven features, voracious culture coverage, sharp opinion, and enlightening conversation. Help us shape our ongoing coverage by responding to a short reader survey.