My love affair with science started about 30 years ago, along the shores of a remnant inland sea. After throwing a juniper log on our bonfire near Mono Lake, Jan asked me: “Do you want to go camping in the desert tomorrow? I’m leaving at 4 a.m. to look for toads.”

She was a biologist, and I wasn’t sure what exactly her research project was, but I pictured campfires, desert sunsets, and shooting stars above a shimmering playa.

“I need someone to hold them while I tag them. They’re pretty big and feisty,” she said, sizing me up for the task.

“Sure,” I said, figuring that life thus far had prepared me for holding a chunky amphibian. I’ve been a nature freak since I was a kid. Once I tried to count all the petals on three different dandelions just to compare the numbers.

Spadefoot toads are desert survivors that can suck moisture out of the soil through their skin and survive long dry spells in dormancy. Jan said her data could help show exactly how long they can stay buried in drying muck. This evolutionary adaptation enables them to sustain populations through drought.

Over the course of several weeks, we visited boggy seeps, alkali lakes, and even cattle ponds in the Basin and Range Province. After measuring soil moisture and water temperatures, we would sometimes watch the toads dig burrows with their spiny spurs.

One night, camped at a hot spring, we took a shot of tequila for every shooting star we saw and talked about science, nature, and conservation. I started understanding how the tiniest puzzle pieces help answer some of life’s biggest questions.

The next day, at a spadefoot stronghold in the Toiyabe Range, as I tried to wrangle a particularly squirmy one, she said, “Hold it tight, like you’re never going to let it go,” and leaned close toward me to mark the toad.

I have loved science ever since.

Science Is a Life-Giving Force

Later that summer, I was exploring Mono Lake’s watershed boundary with Taku, a limnologist who was then a fellow intern with me at the Mono Lake Committee. High in the glacier-carved Twenty Lakes Basin, just outside Yosemite National Park, I watched him fill small vials from the intensely turquoise lake. A chunk of ice off the Conness Glacier floated in the middle.

(Photo: Mono Lake Committee)

After recording the water temperature in a notebook, he said: “This is really cool. This ice is 20,000 years old. Getting samples here will help us understand how the climate is changing.”

We scrambled around jagged boulders trying to figure out a way to move the iceberg toward shore. In the end, Taku swam out and chipped a wedge of ice into a sterile bag—”in the name of science,” he said, mentioning something about how carbon pollution traps heat.

This was just a few years after famed climatologist and activist James Hansen released one of the first significant modern studies on greenhouse gases and climate, in 1981. Global warming was not a big issue yet, and Taku’s comment was the first time I had heard of it.

His main focus at the time was to measure pollutants in mountain lakes from factories and farms, based on early warnings from biologists about amphibians and fish die-offs. A few decades later, data like his was used to develop recovery plans for endangered species, including Sierra Nevada yellow-legged frogs, which are now poised for a comeback. Science can be a life-giving force.

Science Is Activism

In those years, as I got to know activists like David Gaines, I also realized that science isn’t separate from society. Gaines, an ornithologist from the University of California–Davis who had founded the preservationist Mono Lake Committee, brimmed with save-the-world passion, and he was building a grassroots environmental movement that—along with a landmark California Supreme Court ruling—would soon force the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power to consider Mono Lake’s inherent environmental value, and just what it can provide for people.

Discussing the battle for Mono Lake, Gaines said at the time that knowledge gained from science confers moral responsibility and empowers action. The goal was to stop L.A. from diverting most of Mono Lake’s tributary freshwater streams, a policy that was slowly killing the briny lake’s productive ecosystem.

In the pre-Internet days, Gaines’ media campaign included blue Save Mono Lake bumper stickers that became ubiquitous in California. They even showed up on Cadillacs cruising Wilshire Boulevard. Gaines handed them out after giving one of hundreds of slideshow presentations to all kinds of groups in L.A., from Boy Scout troops and Rotary Clubs and to schools and county fairs.

There was never any question in his mind that he would prevail, and, today, Mono Lake is recovering. Water flowing steadily through sage-lined canyons that were dried up for more than 50 years are a living testament to science activism, and to Gaines himself, who died in 1988 in a car accident.

Science Connects the Dots

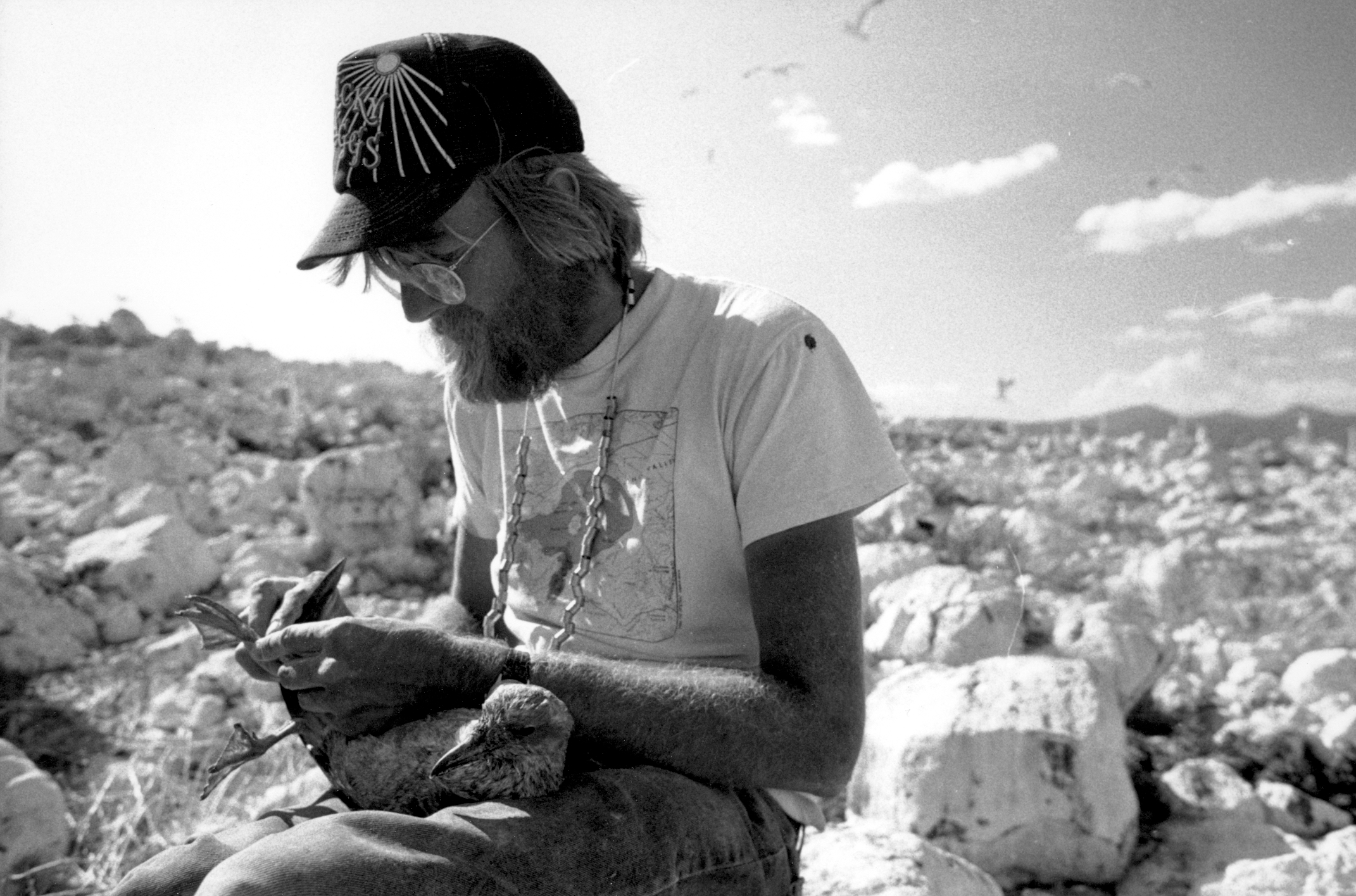

That summer, I camped with other scientists on a tiny volcanic islet in Mono Lake, counting seagull eggs and chicks to determine their survival rate. With its freshwater supply mostly cut off, the lake was growing too salty for the brine shrimp and brine flies at the base of the lake’s simple food web. With less food, more of the chicks were dying.

Over a backgammon table we drew on a cardboard box, entomologist Dave “Bug” Herbst explained how the fate of Mono Lake’s tiny flies and and shrimp have global implications, because they are eaten by birds ranging from as far as Alaska and Tierra del Fuego.

(Photo: Mono Lake Committee)

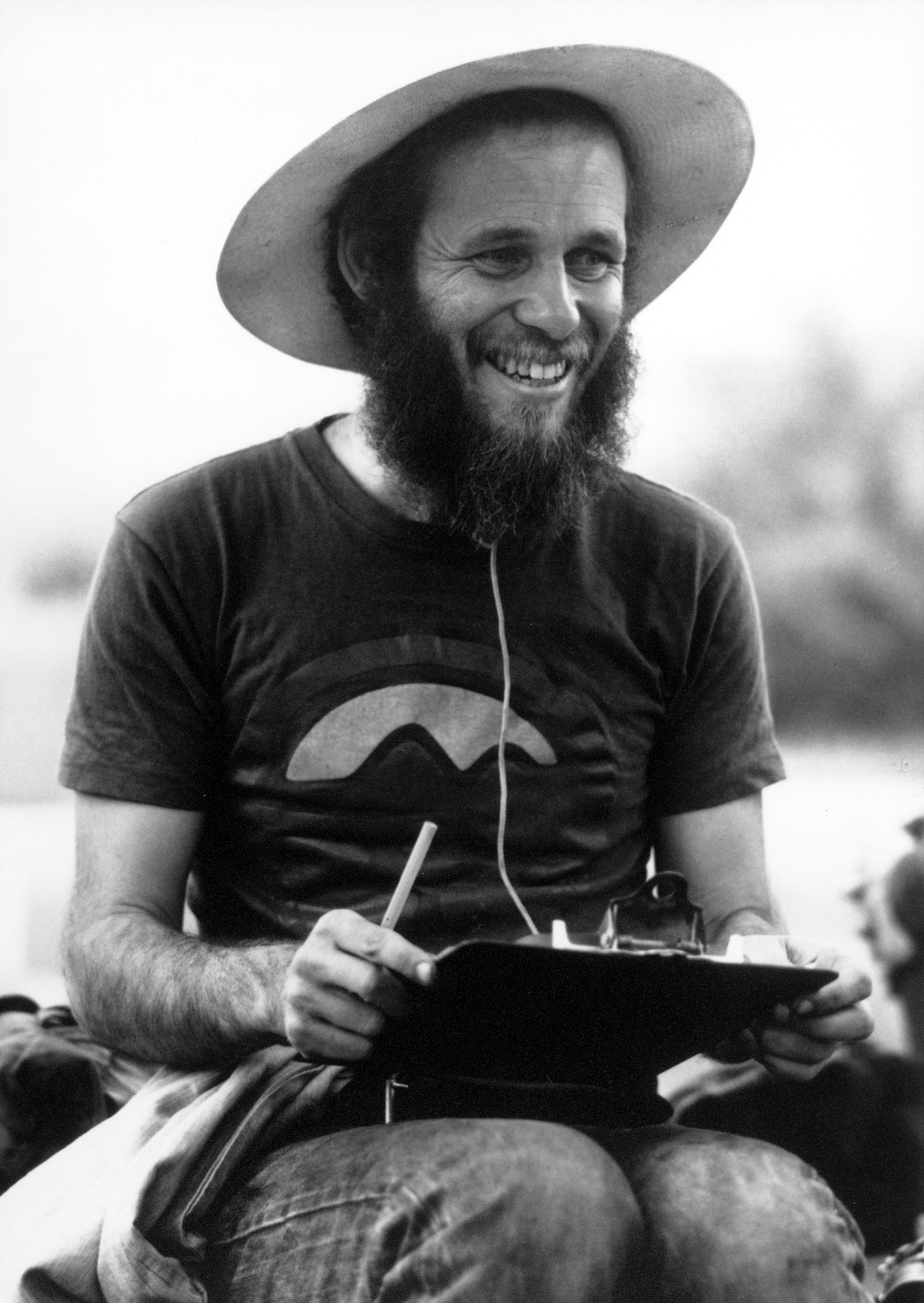

We documented what the gulls were eating. In some cases, it was easy because the chicks would regurgitate the food while we banded. All the while, indignant adults squawked, swooped, and pecked from above. At one point, I felt a big turd plop on the clipboard I was holding over my head.

Unperturbed, gull researcher Dave Shuford scraped the blob with plastic spatula and took a close look with his headlamp. Night is when the gulls are calm.

“If the poop is pink, they’re eating brine shrimp; if it’s black and gray, it’s brine flies. Sometimes it’s mixed, so we try and estimate that too,” he said, adding a checkmark to his survey form.

In a delicate balance with algae and bacteria, the tiny crustaceans and insects power an incredibly productive ecosystem that’s vital to birds. Along with the nesting gulls, who would die or leave if the food supply failed, the lake hosts huge flocks of migratory birds. Up to one million grebes visit. Late in summer, phalaropes use the lake as a refueling station flying on another 7,000 miles non-stop to southern Chile.

Saving the World, One Ecosystem at a Time

Science is a big part of the Mono Lake conservation success story. The ecosystem is recovering, and Los Angeles didn’t wither away. That’s what science can help us do. It’s a rare and wondrous thing in an era of human-driven mass species extinctions, when other similar ecosystems, like the Aral Sea, are dying.

About 15 years after that first summer at Mono Lake, I started writing about endangered species conservation in Colorado, where I saw a similar persistence at work among scientists and activists. I followed biologists into murky bogs at night to track boreal toads. We waded into icy mountain streams to count fish, or to take water samples that would help design a way to treat toxic heavy metals leaking from a mine.

I’ve spent the last 20 years reporting on scientists who work in the field trying to solve environmental problems, and I thought back to all these encounters last month, after a story I wrote about a science hike in the Alps accidentally invoked a stereotype about nerdy lab rats.

After editing and translation, the story’s lead reads: “Scientists aren’t known for being the most outdoorsy types….”

That remark elicited some good-natured backlash from scientists, who responded with a long string of tweets under the #outdoorsyscientist hashtag and a series of photos showing adventurous glaciologists rappelling down ice cliffs, marine biologists diving to restore coral reefs, and snow physicists studying avalanches in the middle of a howling blizzard.

“Scientists aren’t known for being the most outdoorsy types…” pic.twitter.com/06d1kQtauO

— Dr. Karen James (@kejames) September 20, 2017

The point is that scientists can be outdoorsy, and often are. The response on social media—like my own awakening all those years ago—should be enough to dispel any lingering false ideas about scientists being somehow disengaged from the natural world.

If we let them, they can show us how to fix at least some parts of this broken-down planet.