On Wednesday, Governor Jerry Brown signed a new law banning mandatory life sentences without the possibility of parole (LWOP) for juveniles in the state. The bill made California the 20th state to ban life sentences for juvenile offenders, and brought the Golden State in line with a 2012 Supreme Court decision that such sentences constitute cruel and unusual punishment and are, in other words, unconstitutional.

The decision was based on decades of research that show that the frontal lobes in the brain—the seat of impulse control and reasoning—are not fully developed until adulthood, leaving juveniles less capable of considering the consequences of their actions and more susceptible to risky behavior. And, as is the case in the justice system at large, LWOP sentences are disproportionately administered, as I wrote last year:

A 2012 report from the Sentencing Project found that the population of juvenile lifers skews toward black males. Surveying over 1,500 juvenile lifers across the nation between October 2010 and August 2011, the Project found that 97 percent of them were men and a full 60 percent were black. Even more troubling, black juveniles receive life sentences at a rate 10 times higher than that of white juveniles. The majority of survey respondents came from homes marked by abuse, poverty, violence, and parental incarceration. “Because their cases were waived to adult court, these factors—which arguably could mitigate their culpability in the serious crimes for which they were charged—were frequently inadmissible in court proceedings,” the report authors wrote.

Even before the Supreme Court confirmed in 2016 that the decision retroactively applied to adults serving life sentences throughout the nation’s prisons who had been sentenced as juveniles before the 2012 decision, California began granting re-sentencing hearings to LWOP juveniles after 15 years behind bars, but made no guarantee of a parole hearing. The remaining states that have yet to ban juvenile LWOP sentences continue to use re-sentencing hearings to comply with the Supreme Court decision.

The trouble with re-sentencing hearings is that they don’t necessarily give juveniles a “meaningful” shot at a full life after prison, as the Supreme Court decision demands. In Louisiana, for example, the district attorney of East Baton Rouge (and self-described “progressive”), Hillar Moore, is pushing to replace life sentences with death-in-prison sentences—sentences beyond the life expectancy of inmates.

The new legislation in California, co-sponsored by Democratic Senators Ricardo Lara and Holly Mitchell, replaces the need for re-sentencing hearings by ensuring that anyone who was given a life sentence as a minor will become eligible for a youth parole hearing after 25 years behind bars.

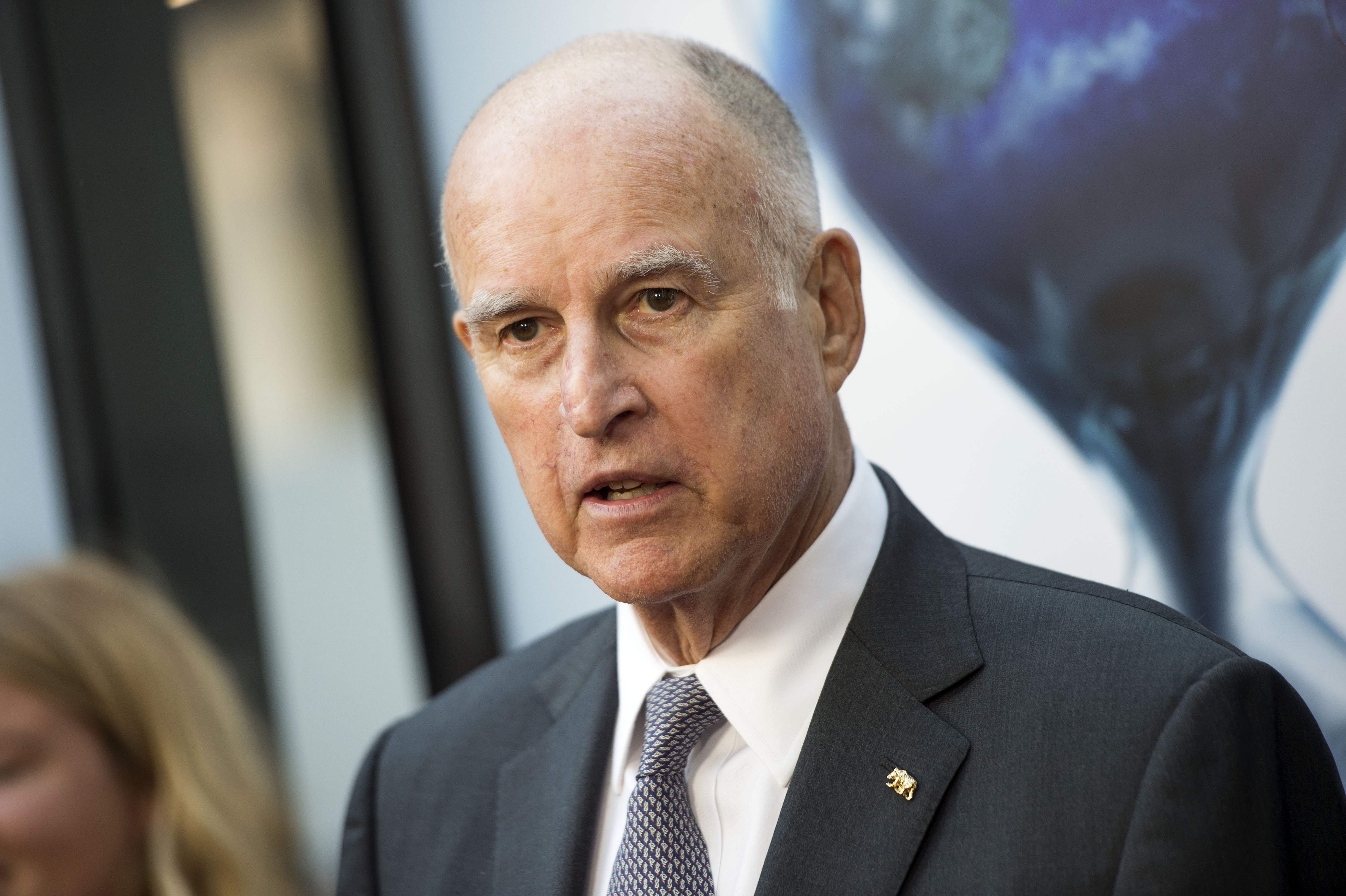

(Photo: Valerie Macon/AFP/Getty Images)

California has had specialized youth parole boards for some time now. Since 2014, minors who were sentenced to life (with the possibility of parole) or received sentences so long they extend beyond average life expectancy—effectively life sentences—were eligible for a hearing after 15 years of incarceration. But a 2016 analysis of the state’s Youth Offender Parole Hearings found that, while the number of juvenile lifers granted parole was about 11 percent higher than adult lifers in California, the specialized parole boards still weren’t considering the neuroscience of juvenile delinquency and culpability.

For one thing, the risk assessment tool parole officials use doesn’t consider an offender’s young age as a mitigating factor, but rather as a risk factor for re-offense. “The law says they have to give great weight to these hallmark features of youth, but at the same time they’re using criteria that are set up for adult offenders,” Beth Caldwell, an associate professor at Southwestern Law School and the author of the 2016 study, told me last year. As I wrote then, it’s incarceration, not youthful offenders’ young age, that increases the risk of recidivism: Research shows that juvenile offenders who end up in the adult prison system are more likely to re-offend than their peers who go through the juvenile justice system.

The new bill would make about 300 people eligible for parole hearings. And while it’s also debatable whether or not juvenile lifers, who Caldwell found spend an average of 27 years incarcerated before being granted parole, still have a “meaningful” shot at a full life upon release in middle age, this latest bill is part of a slew of legislation Brown signed this week to reform the juvenile justice system and reduce prison populations.