This story was produced by the Hechinger Report.

The first time Hsiulien Perez attended Indiana University–Northwest, in the early 1990s, she had just graduated from high school and given birth to her first child. Her mother, an immigrant from Taiwan, and her father, from Mexico, hadn’t gone to college and couldn’t offer any guidance for navigating day-to-day campus life. When her car broke down after a few semesters, a lack of public transit meant she didn’t have any way to get to school. Instead of formally withdrawing, Perez just stopped showing up.

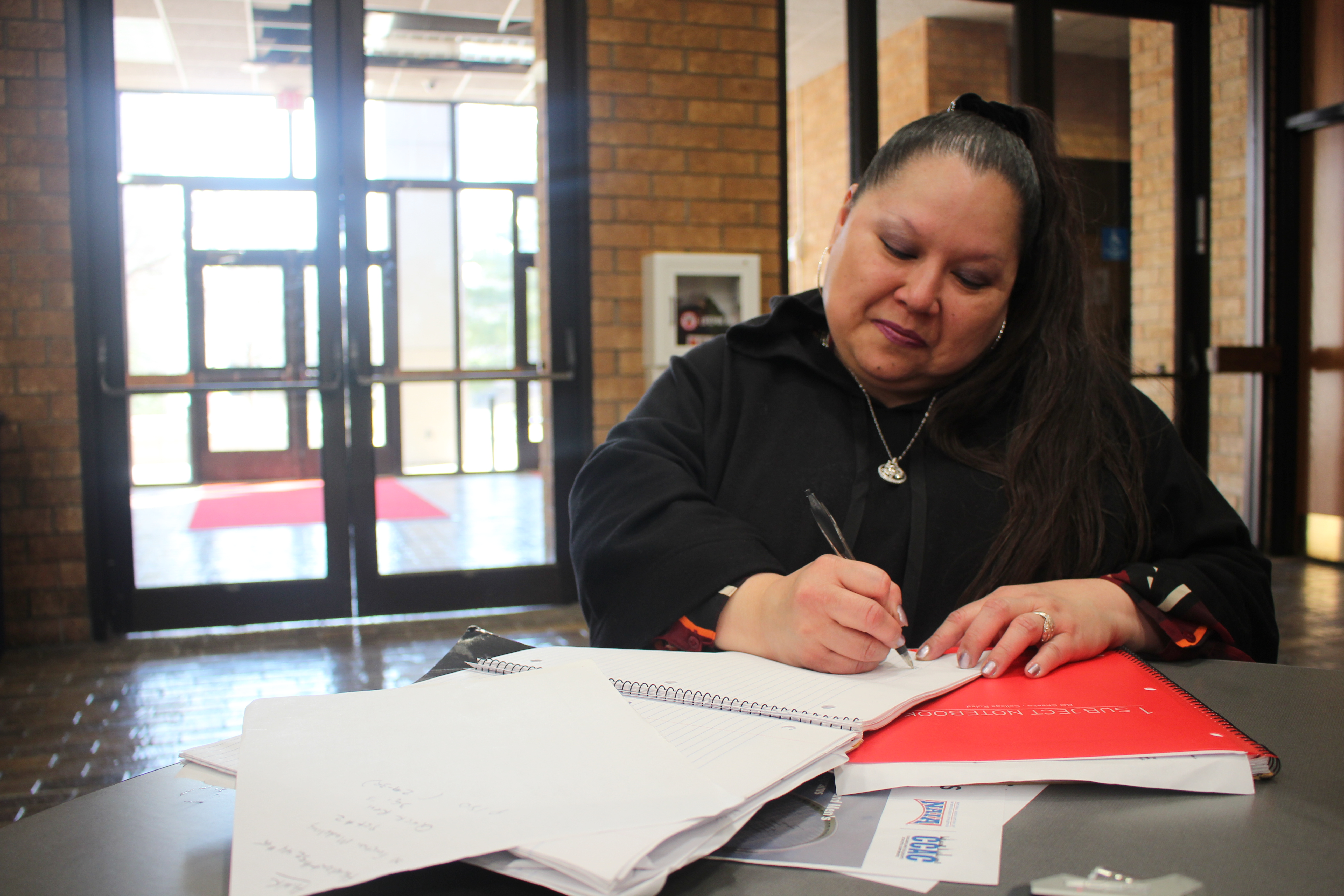

But after years working seasonal jobs sorting equipment at the local Ford plant and dealing blackjack at nearby casinos, Perez wanted to rise to a management position—and she couldn’t without a bachelor’s degree. So in 2016 she headed back to the 42-acre campus near Gary, Indiana’s dilapidated downtown to study for a degree in general studies. “I have two little ones and their dads don’t help me,” says Perez, 45. “I need stability, that’s the word.”

But the odds haven’t been with her. At IU–Northwest in 2017, Latinx students like Perez had a graduation rate of just 28 percent, while the graduation rate for white students was 35 percent. Those numbers reflect a nationwide gap: Latinx are half as likely as non-Hispanic whites to hold a bachelor’s degree, and the gulf has widened since the early 2000s.

Experts say part of the reason so few Latinx students finish college is that they are ending up at overcrowded, underfunded community colleges as well as less-selective universities like IU–Northwest. With Latinx expected to make up 28.6 percent of the population in the United States by 2060, and with well-paying jobs dwindling for workers who don’t hold bachelor’s degrees, pressure is rising on schools like IU–Northwest to tailor their services to help more of these students to and through college.

For decades, in this section of northwest Indiana, the path to the middle class didn’t necessarily route through institutions like IU–Northwest. The steel mills where Perez’s father worked paid good wages to people straight out of high school.

But the loss of many blue-collar jobs since the 1990s and the growth of the Latinx population in this outer ring of metropolitan Chicago have combined to boost Latinx enrollment at the university. From 2008 to 2017, the share of Latinx students at this commuter school of roughly 4,000 rose from 13 percent to 22 percent—the highest of any public university in the state.

Across the country, many universities are seeing similar increases. Between 2000 and 2015, the number of Latinx college students more than doubled, to three million. Their share of overall college enrollment rose between 1996 and 2016 from 8 to 19 percent, according to the United States Census Bureau.

In response, some universities are starting to cater to their growing Latinx populations. They’re adding more faculty who reflect the school’s increasing diversity, introducing cultural programming and establishing counseling and mentoring programs to help Latinx students overcome stubborn academic resource gaps.

(Photo: Aaron Cantú/ The Hechinger Report)

Although Latinx students are not monolithic, they tend to graduate from lower-performing high schools that leave them less prepared for college. Compared to black and white students who don’t identify as Latinx, they are less likely to have parents who attended college.

Closing this educational divide matters for individual students and for the U.S. economy. As manufacturing jobs are replaced by skilled-service positions, Latinx who lack training beyond high school will be increasingly stuck in low-wage and unstable jobs; the resulting lack of skilled workers could depress annual U.S. household incomes by 5 percent by 2060, according to one analysis.

Vicki Román-Lagunas, vice chancellor for academic affairs at IU–Northwest, acknowledges that the university has “a retention problem for every single student on campus” and says that it is trying to usher more students through to the finish line. She blames the high dropout rates on the fact that many students have to juggle school with full- and part-time jobs, leaving little time for academics. And given the former abundance of well-paying, blue-collar jobs in this corner of Indiana, the university is also up against a regional tradition that doesn’t necessarily place a high value on a college degree, she says.

To counteract these realities, Román-Lagunas says her staff members have been analyzing Latinx students’ data—majors, feeder high schools, and retention rates, for example—to see where they can make a difference. Over the past three years, they have introduced an induction ceremony for freshmen (like the inverse of a graduation ceremony), a redesign of introductory courses, and a handful of other initiatives. Those initiatives aren’t explicitly for Latinx, but Román-Lagunas says Latinx students will benefit.

Román-Lagunas, who joined the school two years ago from Northeastern Illinois University in Chicago, where she served as acting provost and professor of Spanish, says she is also focusing on helping the school win more federal grants to make up for gaps in state funding. One big opportunity may be on the horizon.

(Photo: Aaron Cantú/ The Hechinger Report)

Once the school’s Latinx enrollment reaches 25 percent—a milestone she says could happen as soon as next year—it will qualify as a Hispanic-Serving Institution, or HSI. The label from the federal Department of Education is meant to recognize colleges with significant Latinx populations.

It can also unlock up to $1 million in federal grants for schools, which are intended to fund recruitment and retention of Latinx.

“We are really trying to define for IU–Northwest and for Gary what a Hispanic-Serving Institution is,” Román-Lagunas says.

But just because a school qualifies as an HSI doesn’t mean it will win a grant. Last year, just 96 of the roughly 200 HSIs that applied received money, says Beatriz Ceja, division director of the Department of Education’s office of postsecondary education. Since the grant program began in 1994, the number of colleges and universities with at least a 25 percent Latinx student body has risen from 189 to roughly 500 but its budget hasn’t kept pace.

Ceja says the grants are awarded to schools that are “actively recruiting students and wanting to ensure not only that these students get accepted but that they also complete a degree.”

IU–Northwest could be doing more to serve its diversifying student body, according to some students, faculty, and higher-education experts.

The university has struggled to afford practical services that can keep students like Perez from dropping out. It closed its child care center in 2012, citing low demand. And despite a lack of regional public transit, the school has no shuttle system for students in surrounding towns, an issue the university’s chancellor, William J. Lowe, acknowledges.

And some say programs that make Latinx feel welcome on campus have dried up in recent years. Raoul Contreras, a professor who leads the Latino studies program housed in the minority studies department, notes that, in the last year, the school cut a Puerto Rican history class he taught. He attributes the cut to budget concerns—IU–Northwest was the only campus within Indiana University’s higher education system to see a decline in appropriations from FY 2017 to 2018.

A Latinx student group that Contreras advises, ALMA, has also withered, he says, with only a handful of active members now, compared to perhaps two dozen in the 1990s.

Román-Lagunas says she has noticed that “the Latino student groups used to be stronger.” She adds that the school would like to see a resurgence, and is “reaching out to students to see what we can do, whatever it is they want to do as [members of] a Latino student organization.”

Around campus, there are some signs of the university’s outreach to Latinx. Hanging on an office door in Hawthorn Hall, for example, is a pastel-colored advertisement from Student Support Services inviting Latinx students to stop by for help with academic advising, tutoring and mentoring, book and laptop loan programs, and financial literacy education.

But Debra Santiago, chief executive officer of the Washington, D.C.-based advocacy group Excelencia in Education, says universities need to go beyond that sort of passive outreach, especially for students who may be hesitant to seek out help. “We are more likely to trust peers than institutional folks, because we historically haven’t been involved or engaged [in these institutions],” she says of Latinx.

Her group instead touts programs that help students develop a sense of “familia,” like one out of California State University’s East Bay campus that places transfer students into cohorts of peers from similar backgrounds. Student cohorts take required classes together for a year and receive intensive academic and career mentoring throughout their time in college. East Bay transfer students who participated in the program were 10 percent more likely to graduate in three years than other transfer students, according to the school.

At IU–Northwest, in the absence of these kinds of programs, some Latinx students have created their own informal peer cohorts. They keep each other up to date on important deadlines and available resources.

Perez says she only learned of the school’s laptop loan program through another Latina student—after she’d already purchased a new computer. The school’s administration “doesn’t let you know” about such programs, she says on a recent weekday in Hawthorn Hall, wearing silver hoop earrings and shimmering platinum nail polish.

She says that, despite receiving emails about deadlines for scholarships and exit loan counseling, she doesn’t feel connected to the school’s core offices. “They don’t say, ‘We are offering this to Latino students and minorities.’ You don’t see that, you have to explore [on] your own.”

Finding a sense of familia can be decisive in whether students stick around. This was true for Ruby Ortiz, a senior with friendly eyes set behind macchiato-colored glasses.

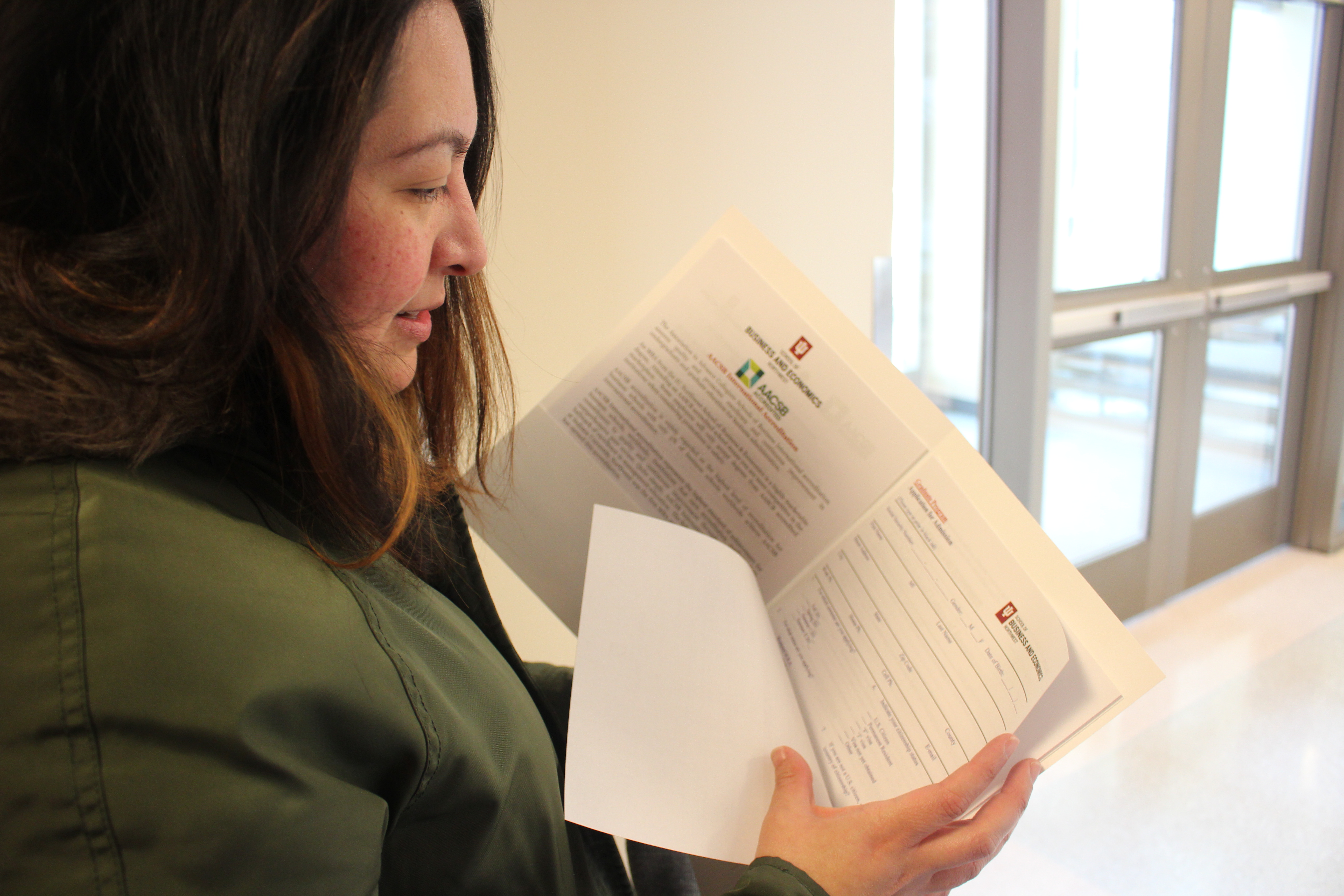

Her first year on campus, Ortiz struggled academically and had a hard time figuring out her financial aid package. She couldn’t rely on her mother, who has never attended college and was just as confused. Ortiz knew she had Pell Grant aid coming in, but didn’t know how to access it. She worked up the courage to approach two other Latina students in one of her freshman classes. They were sisters.

(Photo: Aaron Cantú/ The Hechinger Report)

“I asked [the two sisters] in class, ‘Are you Mexican?’ That’s how we became close,” says Ortiz, whose parents are both from Mexico. “They could answer my questions because they were older than me.”

The sisters had a big influence on her college career, Ortiz says. They encouraged her to switch majors from hygiene to social work. Now she’s hoping to continue at IU–Northwest for a master’s degree in the field.

Connecting with fellow Latinx students can also build solidarity and awareness of one’s social and political circumstances. And that can provide a sense of direction for Latinx students who feel isolated.

Anel Chavez, who graduated from IU–Northwest last year, says she began to understand her own life story through the lenses of race, class, and power after taking a class with Contreras and meeting other Latinx students. At a time when the political climate felt increasingly hostile to Latin American immigrants, it helped to meet with others and talk, and she even started participating in a social justice club. Chavez says her high school teachers “put it in our heads that college is for a select few, or that you go to college and move away and not that you come back and help your people.” She now sees it differently: “Part of me still wants to help my people.”

Perez hopes to join Chavez, her friend, in the labor force soon. Her years of assembly line work at Ford left her with debilitating carpal tunnel syndrome, but Perez says she wants to make it back to the company—off the assembly line, as a manager. “That’s always been my dream,” she says, “to be a supervisor there.”

Earlier this spring, it wasn’t clear when that might happen. Three years into her second stint at IU–Northwest, she’d earned enough credits to walk with other graduates at the school’s commencement in May. But a failing grade on a mid-term in a math class required for graduation threw her plans into question. After many late nights of studying and help from a professor, however, she squeaked by with a C.

Her three children, ages eight, 14, and 26, attended her graduation, along with her parents, sisters, and friends. Now Perez says she’s even considering continuing in school, for a master’s degree in labor studies, while working part-time.

Not long after the ceremony, she wrote in a text, “No matter what age, I am proud to be a first generation Mexican-Taiwanese-American graduate of Indiana University!”

This story about Latinx in higher education was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Hechinger’s newsletter.