Tropical forests inhale staggering amounts of human carbon emissions, storing the greenhouse gas in roots, bark, and wood as trees grow. Tropical forests can offset up to a fifth of all anthropogenic fossil fuel emissions. But when trees are logged, burned, or die and decompose naturally, they become a carbon source. Overall, scientists are still unsure whether tropical forests are more of a carbon sink or carbon source. A new study, published today in Science, offers some grim evidence: It finds tropical forests actually emit more carbon than they absorb.

In the past, researchers often measured the contributions of intact forests and deforested land in tropical regions to the global carbon budget. But it’s not just wholesale deforestation that can lead to carbon losses; even more subtle disturbances, like selective logging or clear cutting, can have dire effects. The traditional remote sensing technologies that researchers use to measure carbon capture across vast tropical regions may not notice these kinds of small-scale changes, but they add up over time and space. In the new study, researchers from Woods Hole Research Center and Boston University combined satellite images, laser remote sensing technology, and on-the-ground measurements gathered from tropical regions in the Americas, Asia, and Africa over 12 years, in order to account for these small-scale changes.

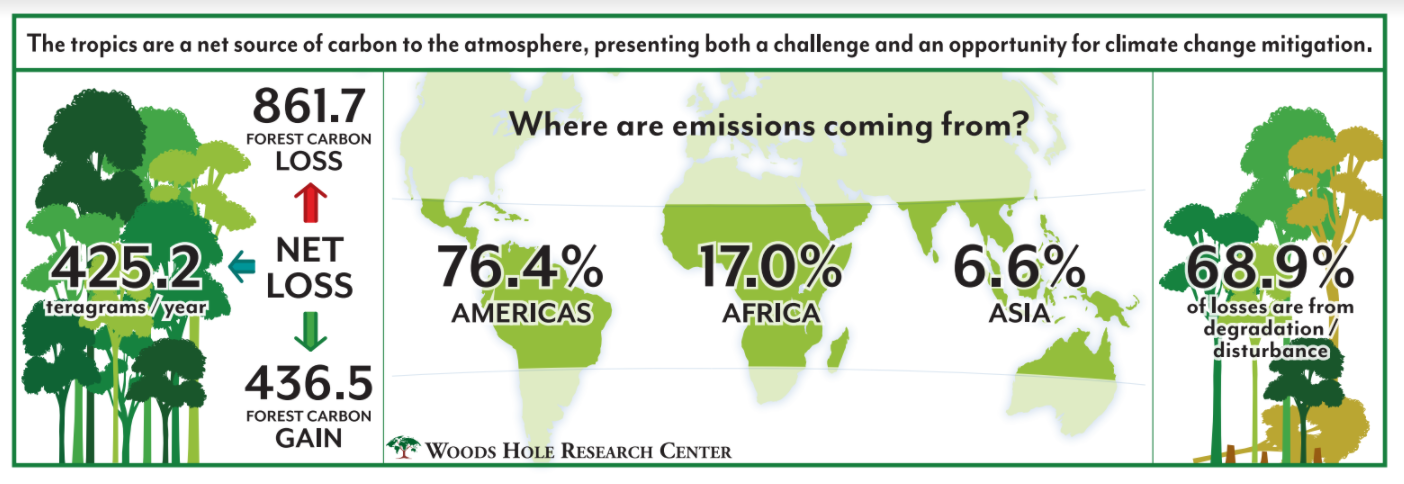

The team found that, across all three regions, tropical forests emitted 862 teragrams of carbon every year—an amount roughly equivalent to half of the United States’ yearly man-made carbon emissions—and absorbed only 425 teragrams of carbon. The majority of the loss—roughly 60 percent—came from Latin American forests, followed by tropical forests in Africa (24 percent) and then Asia (16 percent).

In the Americas and Africa, most of the loss could be chalked up to degradation due to man-made activities like logging, which means humans have plenty of opportunities to change our behavior and the fate of the forests. Governments and non-governmental organizations could even use the tools the researchers used to measure carbon losses and gains across the tropics to identify vulnerable regions.

“With this study, we have lifted the fog that has been hampering local to global efforts to take aggressive action on forests,” Alessandro Baccini, a researcher at Woods Hole and lead author on the new study, said in a statement.

“These findings provide the world with a wake-up call on forests,” he said. “If we’re to keep global temperatures from rising to dangerous levels, we need to drastically reduce emissions and greatly increase forests’ ability to absorb and store carbon. Forests are the only carbon capture and storage ‘technology’ we have in our grasp that is safe, proven, inexpensive, immediately available at scale, and capable of providing beneficial ripple effects—from regulating rainfall patterns to providing livelihoods to indigenous communities.”

Tropical forests could still be the carbon sink we need them to be if we are ever going to meet the goals set by the Paris Agreement; the trick is to stop cutting them down.