Medical tests reportedly indicate that Aaron Hernandez, the former New England Patriots tight end who killed himself in prison after being found guilty of first-degree murder in April of 2015, suffered from a “severe” case of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a degenerative brain disease, at the time of his suicide, his attorney told the Associated Press on Thursday. The results add an alarming layer to Hernandez’s sudden transformation from National Football League “golden boy” to convicted killer.

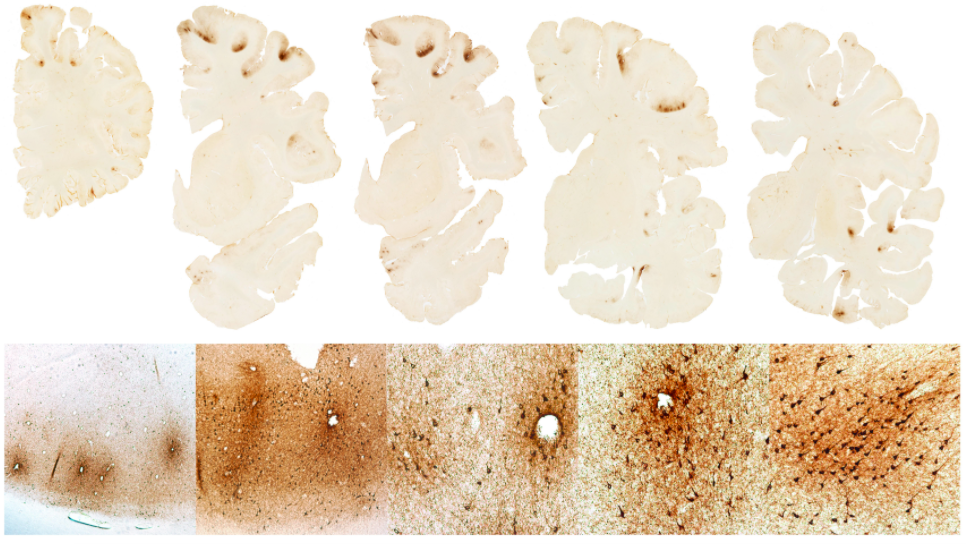

Boston University’s CTE Center chief Ann McKee concluded that Hernandez “had stage 3 of 4 of the disease, and also had early brain atrophy and large perforations in a central membrane” at the time of his death, according to the AP. In light of those results, the Hernandez family is seeking a $1 billion settlement against the NFL for leading the former football star “to believe [football] was safe” and absolving itself of responsibility for his violent actions, according to attorney Jose Baez.

The rough-and-tumble competition of the NFL has gone hand-in-hand with violence off the field for decades, from Javon Belcher’s murder-suicide to Michael Vick’s dog-fighting ring to Ray Rice’s brutal assault of his then-fiancee in an Atlantic City hotel. There’s even debate over whether the infamous double-murder associated with O.J. Simpson could have been influenced by the degenerative brain disease. But it’s only in recent years that CTE—associated with repeated head trauma that manifests in mood swings, memory loss, and erratic behavior, and usually only diagnosed through an autopsy—has been significantly linked to the streak of domestic violence and criminality that plagues the league.

The link between professional football and CTE is, despite the NFL’s intentions, now known to be an indisputable scientific fact. In 2014, research by McKee found that multiple former NFL stars with virtually no history of violent behavior “apparently [became] dangerous to their families” as they began to manifest symptoms of CTE. And in July of 2017, comprehensive research published by McKee in the Journal of the American Medical Association found evidence of CTE in all but one of 111 NFL players, a rate of 99 percent (although previous research put the CTE rate among deceased players closer to 87 percent). A blow to the head is objectively bad for the brain, whether you’re a pro athlete, a member of the armed forces, or a death row inmate. Does CTE lead to the violent tendencies of all three?

(Images: Boston University School of Medicine)

To that end, the core question posed by the Hernandez revelation isn’t about the relationship between football and criminality, but its potential efficacy as a defense. Could Hernandez, on trial for heinous crimes, have claimed not guilty by reason of mental disease or defect? Consider Benedict Omalu, the researcher credited with first diagnosing CTE years ago, and his assertion that O.J. Simpson likely suffered from the brain disease. “He is the most obvious example,” Omalu told ABC News. “He’s been hit on the head more than anyone else. Guaranteed he has CTE.”

The connection between CTE and violent behavior, through persuasive, is less solid than the connection between football and CTE. Although a 2015 analysis of law enforcement data and NFL arrests in the Journal of Criminal Justice indicates that arrest rates are lower than the national average for men between the ages of 20 and 39, FiveThirtyEight points out that professional football players are disproportionately arrested for violent crimes and experience relatively higher arrest rates than their income levels might suggest. When the Ray Rice episode renewed the debate over CTE and violent behavior, 2014 was actually on track to become the least violent year for NFL players in a decade.

Indeed, CTE is statistically less prevalent among professional football players than McKee’s much-hyped 2017 Journal of the American Medical Association study suggests. Those 110 brains weren’t randomly selected, but donated by family members who likely observed CTE symptoms during a player’s life, a self-selection that makes the results likely indicative of the upper bound Daniel Engber, who best articulated the methodological problem here in Slate:

McKee’s findings have been remarkably consistent since she began her work, even as her specimen bank grew from just a handful of former players’ brains to the large collection she has today. Meanwhile, the press coverage has been equally unchanging. In 2011, USA Today reported that McKee had found CTE in the brains of 13 of 14 former NFL players, or 93 percent; CNN followed two months later, citing 14 out of 15, which also rounds to 93 percent. A year after, a Grantland profile of “The Woman Who Would Save Football” reported that McKee had looked at tissue from 19 former players and diagnosed 18 with CTE, a rate of 95 percent. In September 2014, McKee earned a huge amount of coverage for having uncovered signs of CTE in the brains of 76 out of 79 former players, or 96 percent. In September 2015, another round of stories reported on McKee’s “new study” finding CTE in 87 of 91 former players, or 95.6 percent. And now we have the latest news, that there is evidence of CTE in 110 out of 111 former players, or 99 percent.

As the New York Times acknowledged at the time, those 110 players represent only 9 percent of the more than 1,200 professional football players who take the field each year. And, despite new reports of CTE-related evidence among more infamous pros like Hernandez, the declining violent crime rates among football players doesn’t suggest a major uptick in violence. As Engber pointed out in July, a 2008 University of Michigan study of 1,063 NFL retirees found that “young” retirees reported depressive symptoms that could indicate CTE at a “slightly higher” rate (17 percent) than the rest of the country, a rate that gradually declines with age. And although NFL retirees reported significantly higher rates of dementia or memory loss compared to the rest of the population, instances of intermittent explosive disorder (defined as “episodes of unpremeditated and uncontrollable anger”) were significantly less prevalent for retirees. CTE may be a sufficient condition for violence, but it is not clearly a necessary one.

There’s also the matter of other exogenous factors: Living a wild life on the playing field may simply translate to a wild life in the streets, brain injury or not. This is probably best indicated by the “extraordinary” domestic violence and DUI rates among football pros despite their relatively high income level identified by FiveThirtyEight. An NFL player is “prone to high-risk behavior to begin with, and risk-taking individuals tend to be more inclined towards drugs, alcohol, and aggressive behavior,” as Alison Brooks from the University of Wisconsin–Madison told the New Republic after the Ray Rice incident in 2014. “For many of these individuals, any number of additional factors might contribute to violent behavior: steroid use, drug and alcohol abuse, and underlying mental health issues.” CTE may simply exacerbate underlying problems, a trigger rather than root cause of pros propensity for violence.

At the moment, the biggest obstacle to CTE as a legal defense is that it’s diagnostically impossible: CTE can only be confirmed by a brain autopsy after death, which means the only benefit offered by a post-mortem confirmation, according to Sports Illustrated‘s Michael McCann, would come as legal protection against civil lawsuits filed by the family of a player’s victims. As such, recent CTE research has focused on using post-mortem data to diagnose the malady before death.

In terms of an actual trial, the effectiveness of CTE as a pre-mortem legal argument is dependent on testimony of expert witnesses. But perhaps the most instructive case comes out of Hernandez’s home state of Massachusetts: During his trial over the brutal 2011 slaying of his girlfriend Lauren Astley, Nathaniel Fujita claimed that the psychotic episode was triggered by CTE wrought by head injuries endured during his time as a high school football player. After hearing testimony from psychiatrists who examined Fujita, a jury found him guilty of first-degree murder, and he was sentenced to life in prison. CTE may have led men like Hernandez and Fujita on a path to kill, but, when it comes to the emerging field of CTE research, the law hasn’t caught up to the technology (and science) just yet.