In a nostalgic retrospective of President Barack Obama’s best jokes, the Washington Post‘s Emily Heil wrote in April of 2016 that Obama was the country’s “first alt-comedy president.” The former president tended to add “meta, deadpan flourish[es]” to his punchlines, Heil wrote, while his style was “defined by irony, self-awareness, and quirky topical references.”

At the time, David Litt, a speechwriter who helped shape Obama’s monologue material for the White House Correspondents’ Association Dinner, told the Post that those flourishes—the stuff that made Obama’s speeches truly funny—all came from the president. “He would make these little, small changes, but they would make such a difference, [punctuating] the joke in a way that made it work better,” Litt told Heil.

Since he left the White House in 2016, Litt’s penchant for telling self-deprecating anecdotes has not changed.

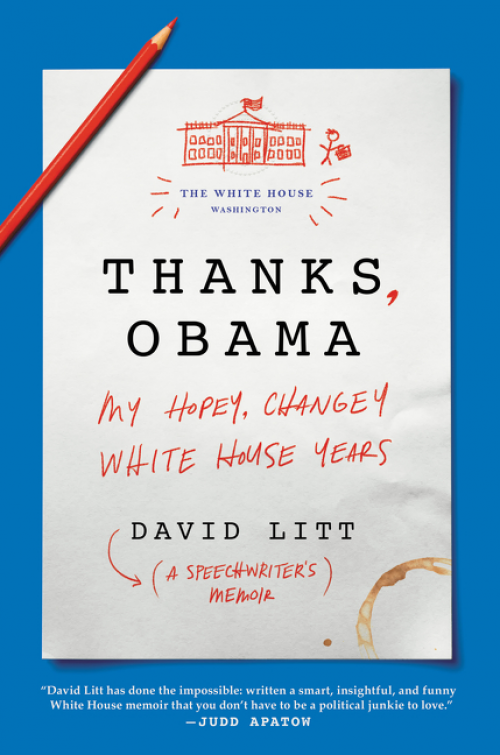

In Thanks, Obama: My Hopey Changey White House Years, an accessible and highly entertaining memoir out today via Ecco Press, Litt chronicles his life orbiting Obama, from the 2008 presidential campaign, when Litt worked as a field organizer in Ohio, to his ascent as speechwriter for a cadre of senior advisers—and, finally, for the president himself.

While it would be easy for a cynic to write off Litt’s effort as an over-earnest love letter to the former president, the book is much more than a scrapbook of Beltway gossip and Obama idolatry. Litt discusses what he wrote, to be sure—he scripted the president’s 2015 address at the NAACP’s national convention and spearheaded Obama’s iconic “anger translator” bit during that year’s White House Correspondents’ Dinner—but he’s also frank about losing hope, at times, in both American politics, and in the president he clearly adores.

Litt spoke recently with Pacific Standard to discuss the role of political comedy in Obama’s administration, and in government today.

The book is very funny but it also has these incredibly sober moments that grapple with some of the more emotional periods of Obama’s time in office. There’s a point where you talk about standing outside the White House the night the Supreme Court ruled on same-sex marriage, and how special it was for those who lived in the city.

It’s funny to think about, especially now—a lot of the coverage of the book has been about its humor, but I also did want to get moments like that in, where every so often in D.C. [there are] these sort of amazing public experiences where everyone is taking part in something that’s part of the national life together. And it happens sort of organically—and D.C. gets a bad rap, but it was a very cool moment to be here.

(Photo: HarperCollins)

One of my favorite passages in the book is in the epilogue, where you reach the conclusion that “once you reach a certain age, the world has no more parents.” I’m wondering at what point in the Obama administration you came to that realization.

I think, for me, it was a gradual process. It sort of started the first day, when I’d always assumed that people who worked in the White House are smarter and less mistake-prone than I was. And then, the moment I walked into the White House I was like, “uh oh, [we’re] the same.” And I remember very early on in a speechwriting meeting, sitting with all of the president’s speechwriters, who I’d looked up to from outside the White House. And I think it was Jon Favreau, the chief speechwriter, who was talking about a speech [we were about to write] said, “All right, so what should [the president] say?” And I was thinking, there’s not an answer here? It’s not something everybody already knows?

Even just walking through the White House in the first few months, you start to get the sense that, wait a second, these are some of the best people I will ever work with, but they’re still just people. And I think, over time, and especially around the first debate with Mitt Romney [during the 2012 presidential election cycle], which really did not go well [for Obama], I started to think that President Obama—who’s really an extraordinary person, and that is an understatement—he’s a person. And I didn’t feel like that was disappointing to me, in the end. I felt like it was liberating.

Let me put it this way: If there isn’t a perfect person who can save us, then it means that all of us have the ability to do something to solve all of the problems that we’re facing. And all of us have the responsibility to try. That’s something that I hope people will take away from the book.

That seems to be a recurring idea. Pretty early on you talk about the “Obamabot”—the staffer that is totally enamored with everything the president says and does, and can see no wrong in his actions. But partway through the book you describe a moment where you’re sitting in a speechwriting meeting and Obama walks in unexpectedly and gives staffers a pep talk. You say you realize that the president has become more human to you, and that you no longer see him as without flaws.

So I will say about that meeting—I wanted to describe a really low point, where I genuinely wasn’t sure that everything that the president had done and everything that we had done on his team was going to be enough. And, in fact, I was pretty sure it wasn’t going to be enough. And I’m happy to say I was wrong, but I did want to talk about how that felt, in part because I think that it’s pretty likely that in the future there will be young White House staffers who are trying to make their own small contribution to America.

I found one of your characterizations of Obama’s humor interesting: That he didn’t necessarily like self-deprecation, but understood that it gave him leeway in attacking his more vocal critics. Did he usually expect his speechwriters to make that trade-off in his remarks?

I think he understood pretty clearly that, when you’re the president of the United States, you’ll end up punching down unless you’re very, very careful. He didn’t believe in doing that. So whether that was throwing in a little self-deprecating humor before doing some truth-telling about some people we felt deserved it, or, sometimes, going after bullies. That’s one thing that President Obama consistently did, whether it was through a joke, or through policy, or through an off-the-cuff remark or a big speech. I think over the course of his career you see a person who really can’t stand it when people are taking advantage of the less powerful. So that was an exception. But I think he understood that, if you’re the president, and you’re trying to punch up with your humor, that’s a challenge. It’s something he was aware of.

There’s a scene from the 2012 Al Smith dinner that highlights that point, I think. You describe Obama’s reticence to aggressively roast Romney in public, and refer to this thinking as “playing the long game.” Is there ever a time for outrageous, potentially offensive comedy?

I think different political moments call for different political tones. I do think that’s something that just about every good president is capable of doing, of switching between attitudes. Because the audience is different, the moment is different. And I will say that, when it comes to a presidential speech, not a joke, I always think about these as a means, not an end. So you start with the outcome that you’re hoping to achieve and work backwards. If we had a major joke that would get a big laugh but would jeopardize something important, then we wouldn’t use it in the speech.

I talk about writing a joke [for the 2011 White House Correspondents’ Dinner] that includes Osama bin Laden in the punchline, and seeing bin Laden get cut [from the monologue], and then the next day the bin Laden raid happened. And I suddenly had that moment when I realized exactly how careful you have to be when you’re writing a president’s jokes.

Is there a joke of yours that never made it into one of Obama’s speeches that you still vociferously defend?

So … yes. It would have been for the 2015 White House Correspondents’ Dinner. The joke was: Washington just legalized marijuana and already we’re seeing the results. For example, Rand Paul just delivered a 13-hour filibuster on whether or not the Taco Bell is still open.

President Obama did not get that joke, and, to be fair, most of the people I talk to don’t think it’s particularly funny. But I’m privately convinced that it’s actually really funny, even if nobody believes me.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.