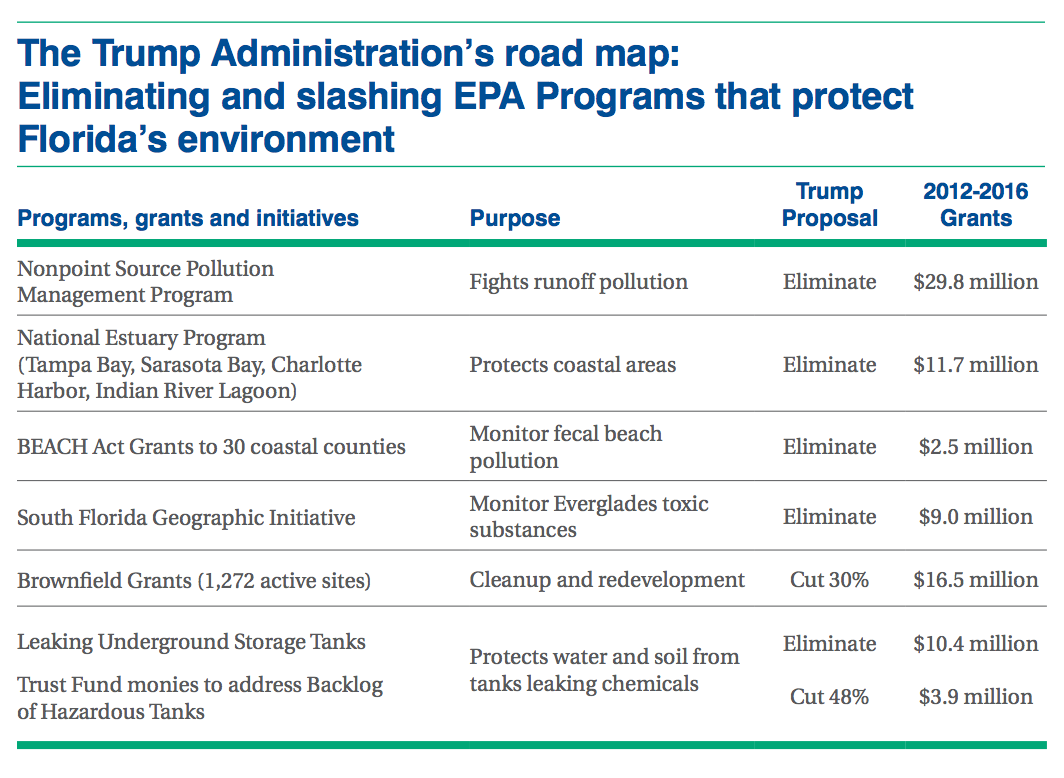

Earlier this year, President Donald Trump revealed a budget blueprint for the 2018 fiscal year that would slash the Environmental Protection Agency’s spending by roughly 30 percent, bringing the agency’s budget down to its lowest levels in more than four decades. Most of those savings come from completely eliminating dozens of programs. Despite the fact that EPA head Scott Pruitt has said programs to clean-up polluted industrial sites and hazardous waste sites—like the Superfund program—would remain a priority, Trump’s budget would cut those programs by 36 percent and 25 percent, respectively.

A new report out today from the Environmental Defense Fund catalogues just how devastating those cuts could be for the state of Florida, which has one of the highest numbers of sites listed on the Superfund National Priorities List in the nation.

(Map: Environmental Defense Fund)

Cuts to hazardous clean-up spending would be particularly harmful to minorities; 44 percent of Americans who live within a one-mile radius of Superfund sites are minorities, according to the EDF report, and in Florida in particular, research shows that cancer rates are up to 6 percent higher in counties that are home to one of the state’s 54 Superfund sites.

(Chart: Environmental Defense Fund)

Beyond impeding clean-up efforts in contaminated regions, the EPA cuts would almost certainly lead to more polluted soil, air, and water in the state, imperiling Florida’s 20 million residents and the more than 112 million tourists who visit the Sunshine State each year. The proposed budget would eliminate grants meant to monitor and reduce pollution from runoff from fertilizers and fecal pollution, both of which lead to harmful algal superblooms.

Trump’s budget would also eliminate the EPA’s South Florida Geographic Initiative, which monitors levels of toxic chemicals like mercury and phosphorus in the Everglades. (Some eight million Florida residents rely on the Everglades for their water supply.)

Of course, Trump’s proposed budget is just that: a proposal, and a statement of the administration’s priorities. In the end, it’s up to Congress to set the spending limits for various federal agencies, and right now it’s still impossible to know how many of these cuts will become law. There’s likely to be lots of last-minute deal-making in Washington before the fiscal year ends on October 1st.