What do prisoners get to read, watch, and play at Guantanamo Bay? For years, journalists who have visited the complex’s detainee library have sketched a vague and intriguing picture: The library, situated behind barbed wire in Camp Delta, contains religious, social science, and philosophy books, among those representing other disciplines, as well as DVDs and video games. Inmates are not allowed to visit, though those who have been on good behavior can have items delivered to them. Many of the books are written or translated into Arabic, though the collection has a sizable English-language section as well, and the collection has grown substantially over the past few years: In 2008, it had 5,000 volumes, and, today, it now has 35,000 volumes—that’s a 700 percent increase in the last nine years, during which time the inmate population fell 83 percent, from 242 inmates to 41.

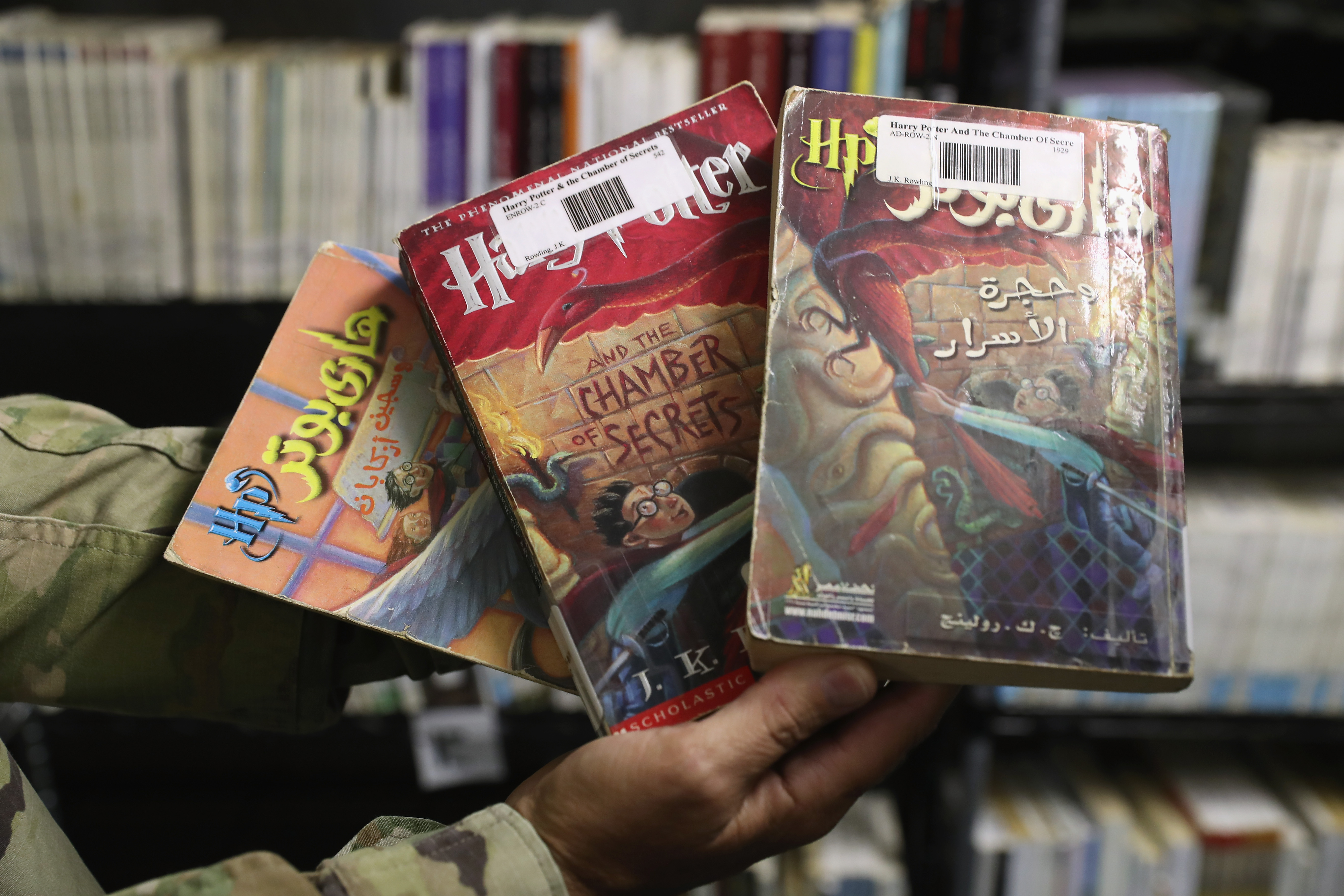

Last week, a response to a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request threw further light on the facility’s collection. On Monday, FOIA logging site Government Attic posted all 634 pages of Guantanamo’s inmate library catalog, which the United States Southern Command’s Joint Task Force-Guantanamo compiled to respond to a July 25th, 2015, request. Some early findings about the collection: Harry Potter is a clear favorite for the collections manager, as the library has versions translated into Farsi, French, German, Russian, and Spanish; inmates have no shortage of titles by conspiracy auteur Dan Brown or mystery maven Agatha Christie; and the collection has lots of DVDs about monuments.

Just how typical is this collection for a prison library? To find out, we spoke with Mary Rootes, a prison librarian who worked in private prisons for the GEO Group in Mississippi, Florida, and Georgia for five years. Most recently, she worked as a librarian for Ingram State Technical College, a state-run institution that serves the correctional population of Alabama.

What is the purpose of a prison library generally?

The first priority is the safety of the institution, and that’s the top priority of any [prison] library. We need to provide [inmates] access to information but in most of the prison libraries, there was a committee that would review materials and determine what was to be omitted, what they could not have access to. Many librarians would say that’s censorship. But in a prison, there are many things that need to be censored. [The secondary goal] was information and recreational reading.

The Guantanamo Bay library has only 41 inmates—down from 242 inmates, before Barack Obama’s presidency—and 35,000 items in the library. Is that typical for a prison that size?

That’s an enormous collection. Most prisons that I worked in were medium-sized prisons, and they had between 1,500 to 1,700 inmates at a time and our collection got up to maybe 10,000 volumes. And I found while looking at it, it had such a variety. The prisons where I worked, when I got to them, the collection was not based on what inmates wanted to read. Many of them, it was what the person who had worked there, what he or she liked to read.

(Photo: John Moore/Getty Images)

What else surprised you about the collection?

Apart from its size, they had more academic books than we had had at the private prisons. There were a lot of books about philosophy and literature: At the prisons where I worked, it was primarily popular literature. There were inmates that wanted to read history and things like that; for that, I would add to the collection. We had some literature, but it was strange: In those prisons, I was part of their education department, but it was separate at the same time. I was not able to work closely with the teacher, [the administration] just saw it as separate.

The prisons where I worked didn’t have a lot of DVDs or videos [like the Guantanamo Bay collection]. At the prisons where I worked the prisoners had access to cable. I was surprised I didn’t see any Stephen King, because he was so popular. That and James Patterson, oh man.

Were there particular titles that came up in this collection that you remember being popular in your library?

I saw Steve Berry—he was very popular—and Dan Brown. Inmates love reading that’s just escapism.

Guantanamo Bay also had video games to keep their prisoners “mentally stimulated” and humanely treated. Is that typical in your experience?

Video games? No, [prisoners where i worked] didn’t have access to any of that. They did not have iPods, but something similar to iPods, for music. In both Alabama and Georgia they’ve been working on giving them access to things that are like iPads, for educational purposes.

What were some of the most in-demand items in your collections when you worked at the prison libraries?

I would have to say James Patterson [books]. James Patterson was too cookie-cutter for some of the more sophisticated readers, but in terms of size, everybody went through James Patterson. They liked thrillers by John Grisham. And fantasy books by Robert Jordan were popular in each of the prisons I went to; they love Robert Jordan. They also loved to read Papillon. That was the book about the man that escaped [the penal colony in French Guinea].

At one time, we had the collection so that the genres were each separate and I re-catalogued them and had them dispersed because people would just congregate, and when inmates congregate, that leads to all kinds of stuff.

(Photo: John Moore/Getty Images)

In 2013, John Kelly, then a Marine general, stopped buying books and subscriptions at Guantanamo Bay to cut down on costs. Is it typical for prisons to cut into library budgets as a cost-saving measure?

We just weren’t very high priority. I would make requests and it would take forever to get anything. I felt like I had to ask because it didn’t seem like we fell very high on the list. I would get $100 a year to buy books and I had a great difficulty getting magazine subscriptions in.

Generally, what would you say about your experience as a prison librarian that might surprise some readers? What did you learn from your time working there?

The inmates generally appreciated the reading. I had much better conversations with some of the inmate trustees than I had with my co-workers. We’d talk about current issues. I try not to think about what they did. It’s important to think of them as human beings.

I feel that a library is so important in a prison. Whether it’s a private or a public prison, it seems that the employees just don’t seem to view education as [being] as important for the inmates. But they are going to be going back into the world. They’ve done terrible things, but we need to try to rehabilitate them. And education is very important in that. These people are going back into the world. We can shortchange them, but we’re all going to be paying the price when they go back into society.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.