Five years after comic book fans split the Internet over news that Anne Hathaway would play Catwoman in The Dark Knight Rises, we’re living through a fresh debate over over who will next wield the whip. The latest impetus was The Hollywood Reporter’s announcement last December that Gotham City Sirens, a comic book series that often features Gotham’s premiere cat burglar, would be adapted into a film. Priyanka Chopra, Rachel Weisz, Charlize Theron, and former Catwoman Anne Hathaway were initially put forward as potential candidates. But fans have since decoded a series of vague social media posts from rising stars Haley Bennett and Eiza Gonzalez and concluded that one may have snagged the role—fanning the inevitable flames of Reddit dissent, as some Redditors argue that both actresses are too young for Ben Affleck’s 45-year-old Caped Crusader.

To some extent, this is par for the course: Fans are always divided over casting choices for beloved comic book heroes, especially on anonymous Internet forums. But Catwoman is an especially divisive character in the publisher’s extended universe simply because she’s been reimagined so many times. Since her first appearance in 1940, Catwoman has been white, black, and Latina; she’s become a man-hating feminist stereotype and a loving wife to Batman; she’s had alternate backstories as an amnesiac stewardess, a battered wife, and a cash-strapped prostitute; and she’s been played by the quintessential performer of “Santa Baby” and by the former Princess of Genovia. Though some of her characteristics have persisted—she’s smart, mischievous but not evil, and sexually liberated, and generally wears some kind of cat get-up—Catwoman’s identity, goals, and especially her costume have transformed throughout the decades, in comics, movies, television, and video games.

(Photo: Chicago Review Press)

Why has Catwoman juggled so many identities? Tim Hanley’s excellent new history, The Many Lives of Catwoman: The Felonious History of a Feline Fatale, suggests that widespread hang-ups about women’s roles in society may be to blame. As a villain, Hanley argues, Catwoman never had to obey contemporary standards of the “good” woman, like heroines Lois Lane and the Invisible Woman—who became wives and mothers in the 1950s, and then women’s libbers in the 1970s. Nevertheless, as a consistently defiant female character, Catwoman has been celebrated or punished in each era she’s lived through, according to the prevailing social mores of the decade: She was cast as an amiable thief in the 1940s, for instance; a supervillain in the paranoid ’50s; an outcast in the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s; and an anti-heroine and feminist icon in the ’90s, 2000s, and ’10s. She’s been transformed at the hands of iconic authors too: Frank Miller demoted her to a prurient side character, whereas Tim Burton redeemed her as a whip-cracking, girl-power icon, and Genevieve Valentine gave her new dimensions as an LGBT heroine in comics.

As Hanley’s history ably shows, Catwoman has long channeled anxieties and excitement over women behaving badly. And while recent anti-heroines like Imperator Furiosa and Jessica Jones and raunchy party comedies like Rough Night and Bridesmaids might suggest America is warming up to the idea, Hanley argues that, for Selina Kyle, newer adaptations haven’t necessarily produced a more empowered character.

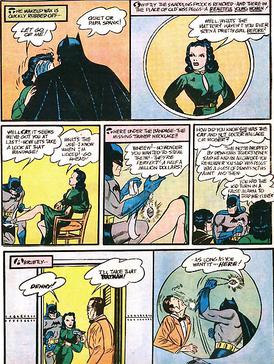

It’s a small miracle that Catwoman has survived into our era of humorless superheroes, given the ridiculousness of her first origin story. “The Cat,” as she was called in 1940’s Batman #1, was a former stewardess who had lost her memory after a plane crash; absent any knowledge of her former self, she turned to robbing people of their precious jewels to survive. When Batman first meets his feline nemesis, she’s posing as an elderly woman on a cruise ship, poised to steal a necklace worth half a million dollars. He knows she’s not who she says she is—the tipoff is that she has “nice legs.” The encounter is sexually charged in other ways as well: When he captures her, he calls himself “Papa” and threatens to spank her; later, as she attempts an escape from the ship, Batman “accidentally” bumps into Robin to prevent him from giving chase.

(Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Catwoman was, indeed, originally introduced to lend sex appeal to the comic strip. Batman had girlfriends at the time, but most were women whom he dated in order to play up his alter ego as the millionaire playboy Bruce Wayne; Catwoman, designed to be an amiable villain, provided Batman near-endless potential for flirtation with crime, and with a shapely woman (co-creator Bob Kane has said her look was inspired by Jean Harlow). Though she was ultimately a marginal villain and romantic interest, playing foil to Batman had its perks: Catwoman was envisioned “as a kind of female Batman,” as Kane wrote in his autobiography. She frequently outsmarted Batman, then charmed him into letting her escape on the rare occasions when he did catch her. And though she had to be a beautiful villainess to do it, Catwoman enjoyed speaking roles in several early Batman comics at a time when women appeared in just 4 percent of Batman panels.

Hanley argues that, in this era, Catwoman resembled a 1940s femme fatale—the contemporaneous film archetype for sexy, manipulative female characters who were often killed off after scheming against male heroes—except that Catwoman, playing against type, survived. In this way, her character “broke the tragic cycle of the femme fatale, embodying all the unique and progressive elements of these characters without the sharp lesson that wiped them away to restore male superiority,” Hanley writes.

But Catwoman’s time as a sexy, independent jewel thief was short-lived: At the start of World War II, comics heroes became model citizens, and heroes began to promote conservative American values, rather than defying them. Catwoman’s refusal to be a good woman was now less of a turn-on than a liability, and, starting in 1943, she fell in love more frequently with Batman than he with her. In one issue, she promised Batman she’d give up a life of crime if she could be with his alter-ego Bruce Wayne (who she didn’t even know was Batman); she later fell in love with Batman himself. In 1950 she even retired from her life as Catwoman and started running a pet shop. The Catwoman had become, well, a Cat Lady.

A woman acting out in comics is never allowed to do so without reprisal for long.

But at least Catwoman was still a supervillain—at this point, she had accessories like a cat-shaped cowl and a “Kitty Car”—until 1954, when psychiatrist Frederic Wertham singled out Catwoman in his bestselling 1954 anti-comics book Seduction of the Innocent. Wertham argued that Catwoman was emblematic of the comics having no “decent, attractive, successful” women, and that Catwoman’s signature whip connoted homosexual deviancy. Wertham’s charge proved a death knell for Catwoman, in an era when comics publishers had begun censoring in-house to avoid government oversight. Not long after Wertham’s screed, Catwoman disappeared for 12 years from the comics, during which time Batman got more wholesome love interests like Batwoman and reporter Vicki Vale.

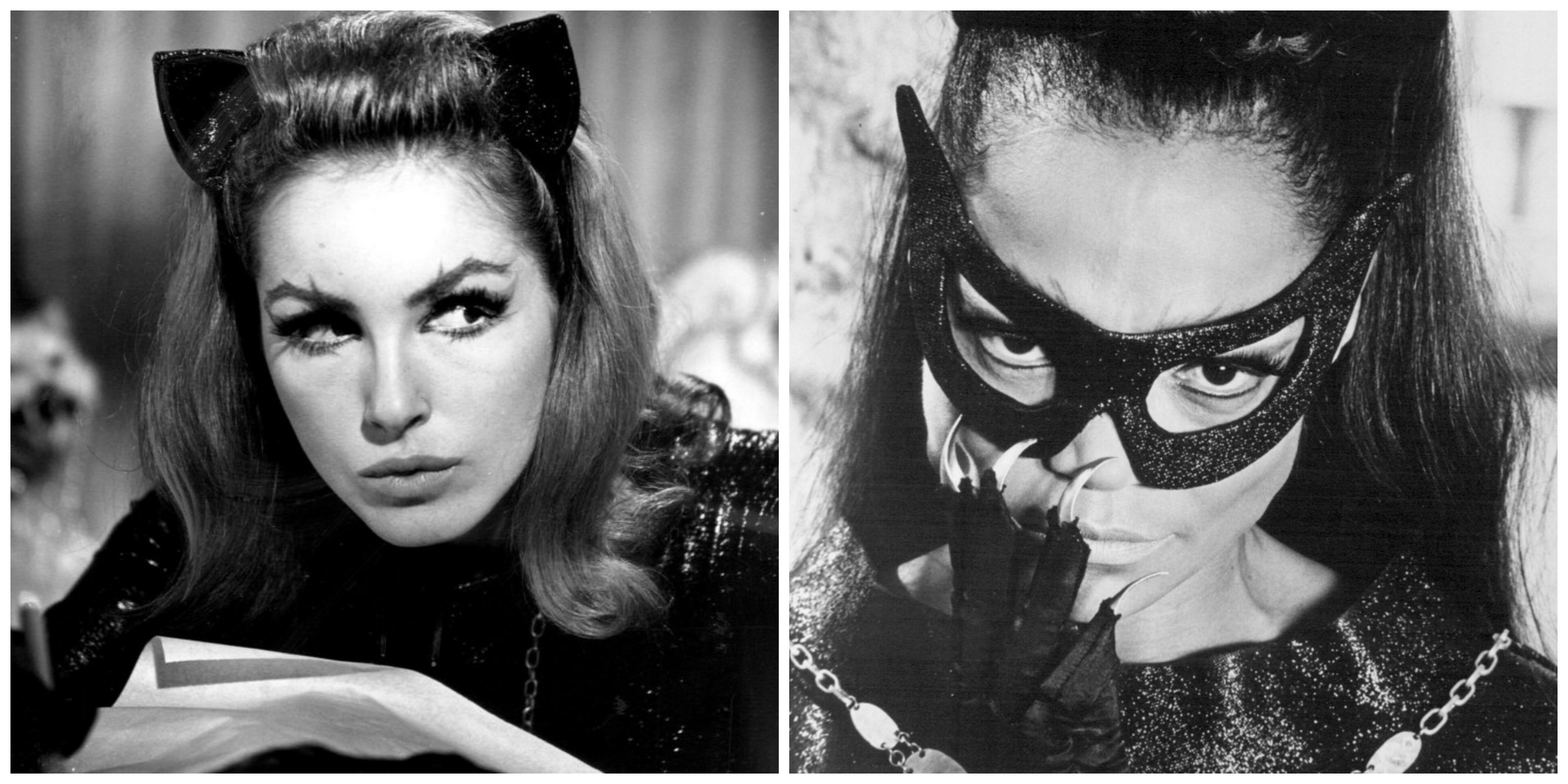

(Photo: ABC/Pacific Standard)

Today, Adam West’s 1960s television show Batman is perhaps best remembered for campy lines like “Holy atomic pile, Batman!” But Hanley argues that, for Catwoman, the show was a major comeback, restoring her reputation as a cold and effective villainess. In the two seasons she was on the show, Julie Newmar’s slinky Catwoman was a romantic interest for Batman, but she was more in lust than in love with him. In one episode, she plotted a trap that would leave him brain-dead, musing: “True, I’d have to sacrifice your intellect…. Oh, well. With a build like yours, who cares?” (Newmar, a dancer, also helped to shape Catwoman’s curvy aesthetic by moving the costume’s belt from her waist to her hips.) In the third season, singer Eartha Kitt took over the role, and while the frequency of romance subplots with Batman declined at this time (Hanley convincingly argues that interracial romance was a tad too edgy for 1960s-era ABC), she proved a commanding force in all her scenes, even giving orders to the Joker. This was radical for the time: The optics of a black woman managing a man in white greasepaint make-up “show[ed] that a black woman not only belonged in the show’s hierarchy of villains but excelled among them,” Hanley writes.

But the era of second-wave feminism wasn’t kind to Catwoman in the comics. When she returned to print in the late ’60s, her brief was not to commit crimes but instead to stalk Batgirl like a jilted lover, jealous of her ex’s new girlfriend; two years later she reappeared as a villainous, self-styled radical feminist leading a group of female convicts in a so-called “War Against the Sexes” that was really a pretense for her to steal a pearl. In the 1970s, she played an extended and humiliating role in the alternate-reality storyline “Crisis on Infinite Earths,” by marrying Batman and becoming a housewife. In the 1980s, Sin City writer and oft–accused misogynist Frank Miller rewrote Catwoman’s backstory to fashion her into a prostitute who specialized in BDSM and was entirely inspired to crime by Batman.

Hanley accounts for Catwoman’s lack of heroic vim in the ’60s and ’70s by noting DC’s financial troubles at the time, which prompted frequent editorial shake-ups and created an inconsistent Catwoman character that had no single canonical backstory, costume, or identity. Catwoman was additionally vilified during this period to make Batgirl—a Ph.D. in library science and crime fighter who feels like DC’s response to feminism’s second wave—look better by comparison. Though Hanley doesn’t linger on this point, it feels like a particularly cruel demotion for Catwoman: Pitting one woman against another in a tired virgin-versus-whore dichotomy may have made the publisher look like it was down with the second wave, but that resulted in neutering the comics’ first truly radical female character. The decision recalls DC’s similarly blockheaded decision to remove Wonder Woman’s powers in the 1970s in order to make her seem more relatable to female readers—which the female editors of Ms. magazine protested in its very first issue. DC had a bad habit of stripping its female characters of powers both literal and figurative to play to the company’s perception of the feminist movement of the day.

(Photo: Warner Bros.)

Hanley argues that Tim Burton’s 1992 film Batman Returns, on the other hand, represents the opposite kind of entertainment: a feminist movie disguised as a standard superhero sequel. Hanley makes a convincing case that Michelle Pfeiffer’s Catwoman is the real hero of the film, thanks in part to her sexually aggressive nature. In her BDSM-inspired black nylon suit, Pfeiffer makes moves on Wayne and Batman but is never defined by her attraction to them; in other words, Hanley argues, Pfeiffer’s Catwoman owns her sexuality. Hanley doesn’t address criticisms that the actress who followed Eartha Kitt as Catwoman was white and impossibly slim. Still, Returns represented a massive step forward for women since Burton’s first Batman (1989), in which Kim Basinger’s journalist Vicki Vale does less investigative reporting than romancing Bruce Wayne, and screams hysterically when the Joker kidnaps her. Pfeiffer’s Catwoman, meanwhile, can best the men in the movie—Batman included—with the elegant use of a whip and zingers like: “You poor guys. Always confusing your pistols with your privates.”

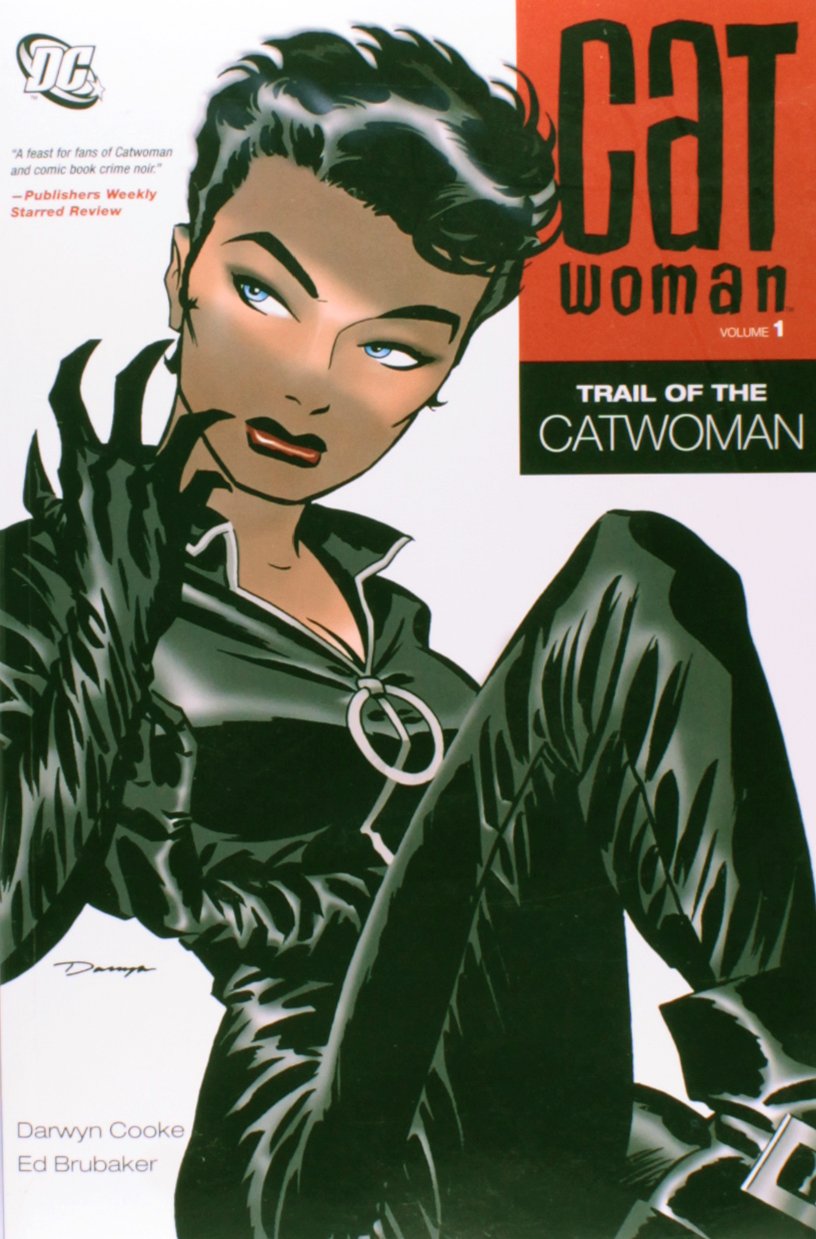

(Photo: DC Comics)

Catwoman kept pace with intersectional feminism as it began to take hold in American culture. In 1993, DC launched Catwoman’s first standalone series, and women authors wrote nearly half of the issues; one of those women writers, Bronwyn Carlton, gave Selina Kyle a Latina mother as part of her backstory. In the early 2000s, author Ed Brubaker and artist Darwyn Cooke redesigned Catwoman’s costume, giving her a pair of goggles and an athletic jumpsuit, and expanded on a sidekick that Miller had introduced named Holly Brubaker. They styled Holly as a lesbian and won a GLAAD Award for the portrayal. And who can forget the 2004 standalone Catwoman film? For its many, many, many failings, it put a woman of color at its center—and no superhero film has centered a woman of color since.

Like Catwoman’s career, Hanley’s book is episodic, arranged according to periods of the villainess’ time in print and on screen. In each chapter, he analyzes the extent to which Catwoman determines her own fate in each of her appearances. If this slightly—and necessarily—piecemeal approach offers any one take-home message, it is that a woman acting out in comics is never allowed to do so without reprisal for long.

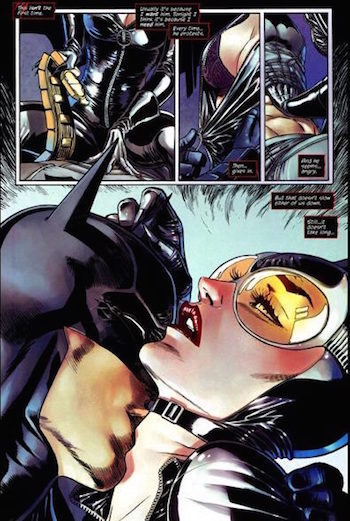

Indeed, lately, Catwoman has endured something of a rough period. The critical and commercial failure of the 2004 film became a justification for executives to stop green-lighting women-centered films, as hacked Sony emails demonstrated in 2014. In the character’s reinvention in 2011’s The New 52 series, Brubaker’s now-classic costume was zipped lower to show Kyle’s cleavage, reflecting the series’ sexed-up narratives. In Batman: Arkham City (2011), the zipper had moved down to her navel, and Catwoman was nearly universally referred to as “bitch.” The Dark Knight Rises, for all the acclaim it received upon arrival, gave Joseph Gordon-Levitt’s character John Blake an ending that hinted at a possible crime-fighting future or expensive spin-off; Anne Hathaway’s Selina Kyle ended the film enjoying a romantic lunch in Italy with Bruce Wayne, which signaled his retirement from crime-fighting but never addressed her promising criminal career. Though one female writer on The New 52—Genevieve Valentine—identified Catwoman as canonically bisexual, overall, in the 2010s, the morally oblique Catwoman has been framed as either a sex object or a romantic interest for heterosexual men.

(Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Hanley’s history vividly demonstrates that, for this female villainess, progress in representation hasn’t been a linear journey, but a periodic perk. Unfortunately, Hanley includes little in the way of big-picture analysis about how Catwoman fits into the larger context of women in comics along the way. In his introduction, Hanley establishes that she’s been exempt from some of the rules that have constrained heroines, but it hasn’t always been true that she’s transcended gendered moral judgment. Catwoman benefited from Americans’ encouragement of professional women in the interwar years, as did the women themselves; she suffered from DC’s attempt to reaffirm traditionally feminine values at the dawn of the second wave of feminism. Catwoman may be an exceptional woman in DC Comics, but she ultimately still struggles against some of the same disadvantages as her heroic compatriots.

The unequal playing field for women in comics is familiar territory for Hanley, who has written books on Lois Lane and Wonder Woman and writes a monthly column for bleedingcool.com tallying the numbers of female creators and characters at Marvel and DC. His perspective on the gender dynamics in the industry could have been useful here: Hanley doesn’t talk much about how other female protagonists were treated in the comics in the periods he covers, nor to what extent Catwoman’s female creators had decision-making power at DC, even when they had recurring bylines on the comics.

These details might have shed light on some of the more baffling parts of his book (why, for instance, in the late 2000s and early 2010s, during entertainment’s peak-antihero craze, was Catwoman such a shallow character?). Such details could have helped identify contexts that allow female villains, not mere icons of virtue, to thrive. Today, Catwoman is again out of print as a standalone comic; she’s now a side character in a Batman comic who is helping make the Dark Knight seem more human. A recent storyline showed Batman proposing to her as an expression of his vulnerability. The character is due for another reinvention: Understanding the broader story of how she got her first few empowering reboots could help DC put her on the path to a new one.