Nearly all Californians get clean, safe drinking water delivered to their homes. But, according to state data, turning on the tap is risky for more than one million people in the San Joaquin Valley, where drinking water is among the most contaminated nationwide, according to government testing. And some residents don’t even know it, as testing of private wells is not required and some water agencies fail to provide customers with required water quality reports or it’s in a language they can’t read.

Most affected are small, rural communities, which are disproportionately poor and Latino. Long-term fixes are in the works but many solutions will take years to implement—not enough funding is available for the people who need help immediately.

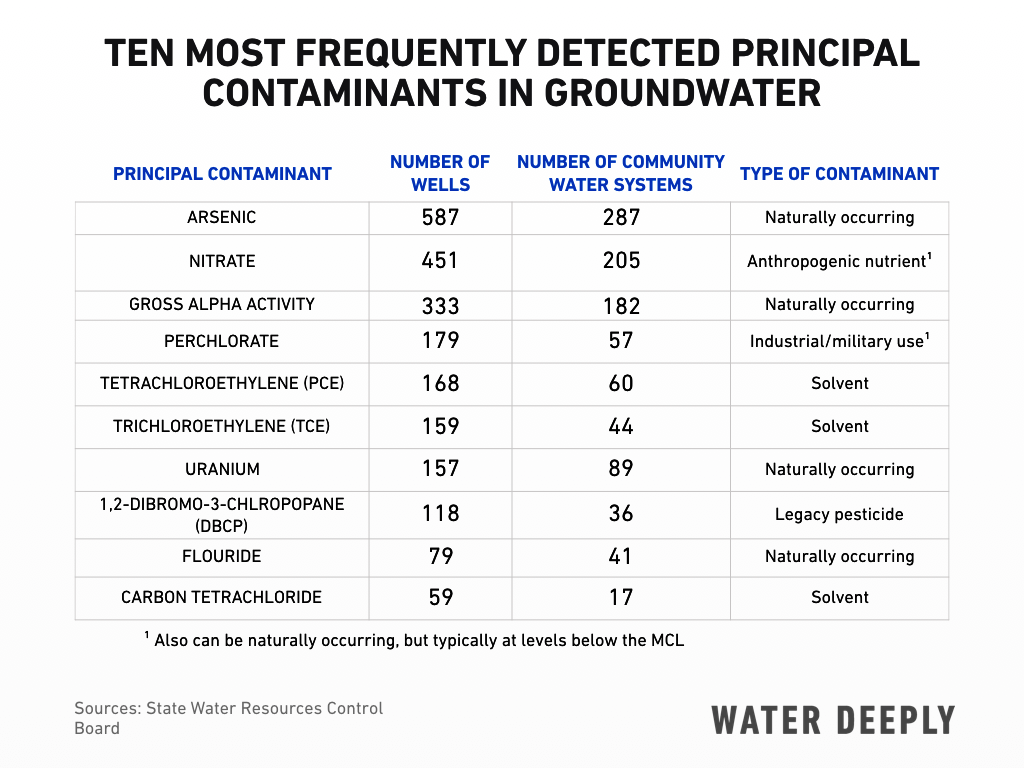

The majority of residents in the San Joaquin Valley rely on groundwater for some or all of their drinking water, and many California groundwater basins are contaminated with a mix of manmade and naturally occurring toxicants. The former include nitrate and legacy pesticides, which persist in the environment long after first introduced, and the latter include arsenic and uranium.

(Photo: Tara Lohan)

Most water suppliers can bring groundwater up to health standards by treating it or blending it with water from cleaner sources. But some communities get all their water from contaminated aquifers and can’t afford to treat it properly, which can threaten public health, according to a report by the State Water Resources Control Board. In Tulare County, for instance, contaminated groundwater is the source of drinking water for 99 percent of the population.

Nitrate is one of the state’s most widespread groundwater contaminants, according to research from the University of California–Davis, which reported that nitrate-contaminated groundwater poses public-health risks for approximately 254,000 people living in two of the biggest agricultural areas of the state: the San Joaquin Valley’s Tulare Lake Basin and the Salinas Valley. California set the drinking water standard for nitrate in 1962 and has regulated water quality since 1969.

Nitrate is an inorganic compound formed when nitrogen combines with oxygen or ozone. Low levels can occur naturally in groundwater, but high levels of nitrate in groundwater are often attributed to fertilizers, septic systems, animal feedlots, or industrial waste, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In California, the state is only just starting to address the primary source of this contaminant in the San Joaquin Valley’s groundwater: the Valley’s five million acres (two million hectares) of farmland. A study led by Thomas Harter and Jay Lund of UC–Davis found that, in the state’s main agricultural counties, 96 percent of the human-generated nitrate in groundwater came from cropland. The biggest sources were synthetic fertilizer (54 percent) and animal manure (33 percent). Fertilizer application followed by irrigation drives excess nitrate down through the soil and into aquifers.

Nitrate can be dangerous to human health, especially for infants. It limits the oxygen that red blood cells carry, a condition known as methemoglobinemia or “blue baby syndrome,” which can result in lethargy, dizziness, and death. The International Agency for Research on Cancer has also concluded that nitrates are a probable human carcinogen.

The San Joaquin Valley is particularly hard hit by nitrate: 63 percent of the state’s public water systems that report violations of health standards for the contaminant in 2015 were in the Valley. “Nitrate is the most critical, the most immediate contaminant in the San Joaquin Valley,” Harter says.

(Photo: Tara Lohan)

When Harter began studying the contaminant as a graduate student in the 1980s, his advisor called nitrate an old problem “from the 1950s.” Why has nitrate taken so long to regulate? For one thing, agriculture was exempt from water quality regulations until 2003. Moreover, it’s hard to determine the source of nitrate pollution in the Valley. “There’s an endless string of fields across the landscape,” Harter says. “It’s unclear who’s contributing how much.”

State regulators are in the second year of a program to help keep agricultural nitrate out of groundwater in the Central Valley. The idea is for farmers to track applications of fertilizer, which contains nitrate, and yields of crops, which consume nitrate as they grow. The difference between the two is the amount of leftover nitrate that can leach into groundwater.

But even if nitrate stopped seeping into groundwater completely, so much has already entered the soil that it will still be a problem for years to come, according to the UC–Davis report. “We understand the urgency—but we need science-based solutions,” says Sue McConnell, chief of the Central Valley Regional Water Quality Control Board’s Irrigated Lands Regulatory Program. “What we’re doing now will help protect future generations.”

Other major human sources of groundwater contaminants in the San Joaquin Valley include pesticides that are banned but still linger in the environment. Notably, the fumigant 1,2-Dibromo-3-Chloropropane (DBCP) was banned in California in 1977 but continues to contaminate groundwater. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, DBCP is classified as a probable carcinogen and chronic exposure to can decrease sperm counts. The San Joaquin Valley has three of the four California counties with the highest DBCP levels, which are triple that deemed to be safe by the state.

Contaminants that occur naturally are even more prevalent in San Joaquin Valley groundwater. One of the most harmful is arsenic, which can cause blindness and partial paralysis, and is linked to cancer. In 2015, 60 percent of the state’s public water systems reporting health violations for arsenic were in the Valley, and Madera County drinking water has the highest levels of arsenic statewide. Another naturally occurring toxicant found in the soil is uranium. Madera County drinking water has the state’s highest levels of uranium at more than three times the health standard.

Another source of water contamination are the 1,000 or so unlined pits in which the oil industry disposes of wastewater, which can contain toxic metals, benzene, and radioactive substances. Like California’s petroleum industry, these pits are concentrated in Kern County and more than 400 of them lack the required state permits necessary to operate, according to the state water board. Without proper management, unlined pits can threaten groundwater quality, the Central Valley Regional Water Quality Control Board reports.

(Photo: Tara Lohan)

Then there are contaminants that are not yet regulated, such as 1,2,3-Trichloropropane (1,2,3-TCP). A solvent found in industrial or hazardous waste sites, 1,2,3-TCP is recognized by California as a carcinogen. This toxicant was also added to two soil fumigants manufactured by Dow Chemical and Shell that were widely used by farmers for decades in the San Joaquin Valley. In 2016, 63 percent of California public water systems that detected this carcinogen were in the Valley.

Jonathan Nelson grew up in Bakersfield, and didn’t know he’d been drinking 1,2,3-TCP-contaminated water his whole life. He only found out when he started working as policy director at the Community Water Center, which advocates for safe drinking water in the San Joaquin Valley, and he realized his town was one that had found the contaminant in its drinking water. Now, thanks partly to his own efforts and his colleagues at the Community Water Center who have lobbied the state for 1,2,3-TCP to be regulated, state officials are expected to announce a maximum contaminant level for 1,2,3-TCP in drinking water this year.

Nelson says drinking water advocates estimate a capital funding need of up to a billion dollars, which would need to be addressed in a future water bond. Another need is an ongoing operations and maintenance fund ranging up to a few hundred million annually, which advocates hope to address through S.B. 623—a bill that has passed the state senate and is before the assembly. “California is the sixth largest economy in the world,” Nelson says. “But people lack safe drinking water in our own backyard.”

Even when drinking water contains known toxins, it can be hard to prove that any single one affects people’s health. One reason is size—impacted communities can be too small for tracking cancer rates or birth defects, says John Capitman, executive director of the Central Valley Health Policy Institute and professor of public health at California State University–Fresno.

Another obstacle: Many Valley residents face contaminants from multiple sources. People who drink polluted water can also breathe polluted air and be exposed to toxic chemicals from pesticide applications, industrial facilities, and hazardous waste landfills.

And the impact of these multiple health burdens is unknown. “We don’t know how air pollution impacts the body differently from water pollution or how multiple effects work out,” Capitman says. “That is a whole new area of science that is absent yet. How do we understand exposure over time and exposure to multiple sources of pollutants? There is huge work to be done in that area.”

This article originally appeared on Water Deeply. You can find the original here. For important news about water issues and the American West, you can sign up to the Water Deeply email list.