Five years ago, a man’s trajectory into misogynistic beliefs and extremist Web forums culminated with him killing six people and wounding 13 others in a murderous rampage near the University of California–Santa Barbara. In the hours after uploading a despairing and hateful YouTube video announcing his attack, he stabbed three of his roommates to death, unsuccessfully attempted to gain entry to a sorority house, and shot numerous bystanders as he drove around Isla Vista, California, before taking his own life.

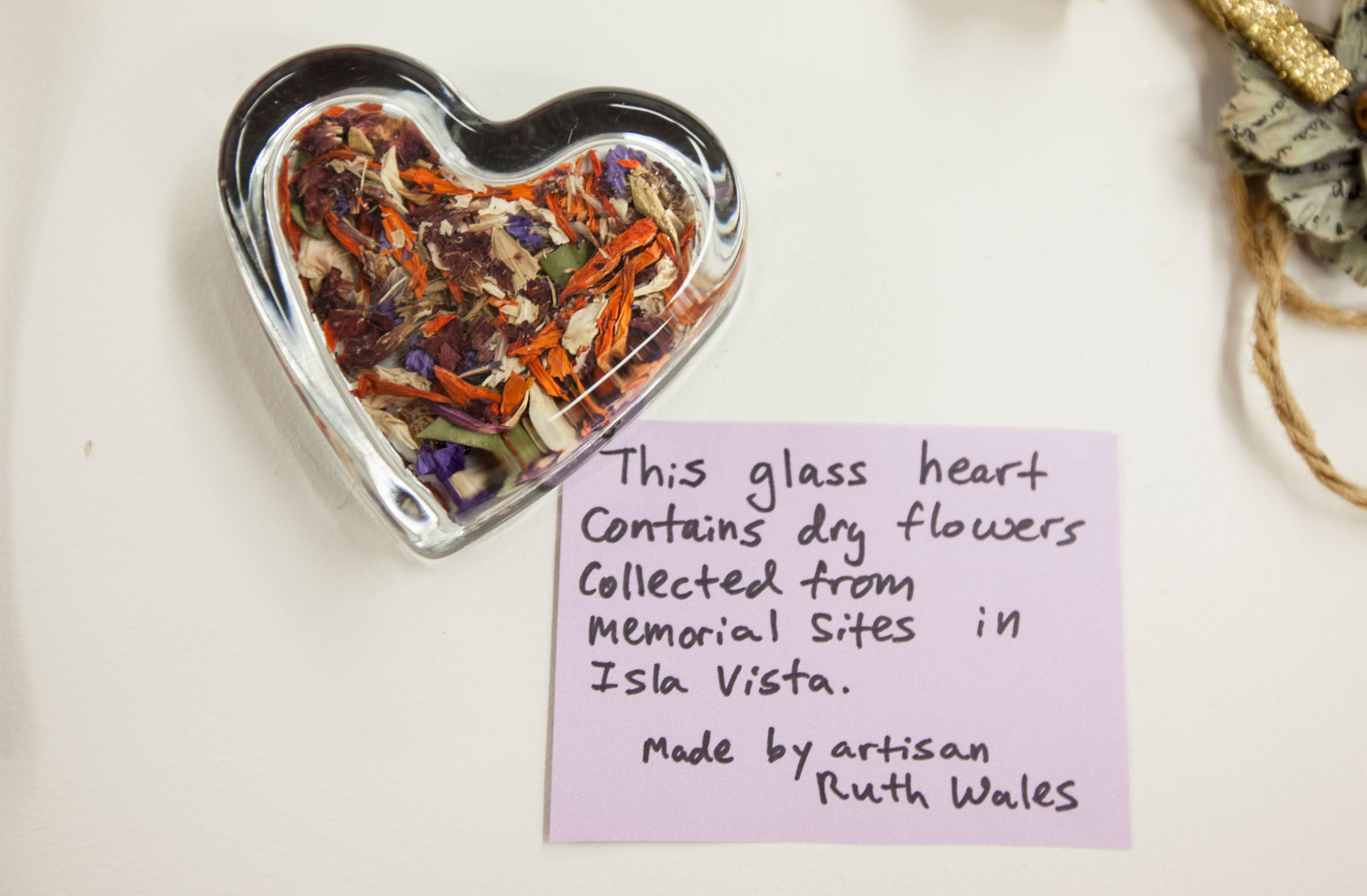

At the time, Lauren Trujillo was a sophomore at UCSB with an internship at a local library’s archives, when three of her sorority sisters were shot during the attack. In the mourning period that followed, Trujillo was asked by a former teaching assistant to join the Isla Vista Memorial Project, which was beginning to collect and preserve the mementos left at memorial sites: a postcard addressed to the National Rifle Association, a colorful bracelet of beads, a funerary message in a bottle, handwritten sticky notes left for the victims, banners of support and anger that hung around Isla Vista.

That collection eventually became a local exhibition of grief, We Remember Them: Acts of Love and Compassion in Isla Vista, which was on display at UCSB during the summer of 2015. This week—in commemoration of the attack’s fifth anniversary—the Isla Vista Memorial Project and Trujillo, who will graduate with her masters in information and library science from University of California–Los Angeles in June, have released an online archive documenting “condolence items left at spontaneous memorial sites, as well as items sent to the university in the wake of the incident that occurred.”

Pacific Standard spoke to Trujillo about the complications of making private mourning public, online archiving, her frustrations with media coverage of tragedies, and how she sees the Memorial Archive as a reclamation of her community’s narratives of grief.

Some of these memorials are deeply personal. Why do you think it’s important to publicly preserve and display them for people whose own lives might not have been affected by the attacks?

One thing that I’ve learned, especially with working with other communities—I presented at conferences with people from the 9/11 Memorial Museum, the Clark County Museum about the Las Vegas Shooting, the organizations collecting items and stories from Pulse nightclub, and the Charleston shooting—is the preservation of memorial items has to be community driven. If the community doesn’t want to see these things displayed, or feels no connection to them, or if they feel it’s inappropriate, then you respect those wishes. You can’t force an archive onto the community.

A lot of communities have dealt with it in different ways. Our community and students felt that it was important to save these items. Whereas Texas A&M—which didn’t have a mass shooting, but lost many students in the ’90s when a woodpile that they stacked up and burned in celebration of homecoming fell and and [11] students died—had huge memorials, and preserved them all. But instead of displaying them, they created a dark archive, meaning it’s all archived, but no one can access it. It just sits there. That was what the community wanted to do.

Our situation is our community felt it was important to save the items, to aid the understanding of what happened, and to start conversations about what’s next. Hopefully it can provide a space for the kind of conversations that can come from looking at pair of shoes that belonged to one of the victims, a poster that says “Media Go Home,” or a video that Joe Biden sent the university wishing the graduates of 2014 goodwill and strength.

What kind of conversations can be started by a pair of shoes?

A pair of shoes has a story. This pair belonged to Veronika, and were brought to a memorial site by one of our friends, and somebody left one of Chris‘ shoes too. Chris was a victim who was shot at IV Deli. His dad is Richard Martinez, who’s been speaking very publicly since the attack. But an empty pair of shoes is not only a metaphor of someone no longer being with us. The shoes are representative of who these people were, and that’s something that we get away from when we talk about these [kind of tragedies]—who these people were, and their stories before the shooting. They get locked in time as victims, and not as water polo players or basketball players. When the families of victims get active in the community and become speakers—people like Richard Martinez—they so clearly want to serve their kids’ stories, who they were, and the difference they made on this planet before their lives were robbed. And the media coverage often gets away from that.

Why create an online archive of these memorials, rather than keep them on display in a physical space?

We do have the physical items in store at the UCSB Special Collections library. They were donated from our organization to the library, which is great, because the university has the proper conditions to store and take care of them.

As we come to the five-year anniversary, there’s this weird situation where most of the students at UCSB were not there when it happened and don’t have a recollection of the event. So my goal with this online exhibition was to create an online space for alumni or community members that have moved on from Santa Barbara, so they can access these materials and find comfort, or resilience, or just memories.

When Las Vegas processed their collection [after the 2017 shooting], they immediately put their items online. And that was important for them, because 58 people were killed, but most of the people attending that music festival did not live in Las Vegas. So the people who were impacted and who felt a connection to it, who may have left things at the memorials—many of them were visiting Las Vegas, and don’t live there.

Virtual spaces are also important because many of these physical memorial spaces don’t become long-term memorials like the 9/11 Memorial. They are temporary, and then they’re cleaned up. In Las Vegas it was the front of a hotel; they’re not going to want a permanent memorial in front of their business.

What proportion of the initial grieving and memorial process in 2014 took place online, as opposed to in physical spaces in Isla Vista? Is any of that online grieving preserved in the archive?

In 2014, our community was grieving together in person. Isla Vista is a very small community. Everyone knows each other, or is willing to get to know each other. So healing together in person was definitely how our community dealt with it and grew, and powered through this awful situation. But in the years since (and a little bit at the time), social media—Facebook and Twitter—has been used to share stories. And that’s one thing that we didn’t preserve, and that are really hard to find now: those conversations on Twitter and Facebook.

It’s really common that when somebody passes away that their Facebook becomes a memorial page. And so, for example, Katie and Veronika’s Facebook pages are full of comments saying “Today I thought of you when I went to the beach,” and “I remember this one time, you were there.” Every time it’s their birthday, we write messages of happy birthday. I’m curious to see how long we stay in conversation with them.

But our collection is not preserving those things on social media. The parents run both of their Facebook accounts, and I think they’d prefer if it were private. But other families might not feel that way about these things—might want the public to see the conversation.

Without oversimplifying the causes behind the attack, it’s my understanding that the misogynistic and extremist online communities that the Isla Vista attacker belonged to were a component of his radicalization. In that context, do you view the online archives as a kind of political response—that by documenting the effects of the tragedy online, you’re standing in opposition to the control of the Internet by these toxic communities?

I don’t see our site or the online exhibition as political. It’s focused on healing and resilience, and showing what the community did in the aftermath of the attacks. While we included politically focused things like Not One More—the movement Richard Martinez started—we also included other people’s perspectives on the issues.

But I do know that the media focus on [the attacker] and his relationship to the incel community has been fuel for them, which is awful. And we see this trend of it through so many of these shootings: The media plays into [the attacker’s] story—over-sharing all the details. And I think that that created a spark that didn’t need to be sparked. I get that the media wanted to speak to prevalent issues, but by doing interviews with his father and asking him all these things, they sort of turned the shooter into a martyr.

If you look at the recent shooting in New Zealand, [the prime minister] decided not to mention the perpetrator whatsoever. And that is what [experts] have been saying since Columbine, but the media so often ignores that to tell the story they want to tell. Which is unfortunate.

It sounds like you, and perhaps your peers, were very frustrated with the media coverage that followed the 2014 attacks in Isla Vista.

My personal experience with the media in the wake of the attack was awful. Our sorority was told not to leave the house because there were cameras waiting outside. We couldn’t really even go to the memorial sites until after a certain hour, because they’d be there filming us.

When we went to church to honor the victims, the media was there in the pew in front of us, filming us crying in church. It was beyond uncomfortable, and unbelievable.

We got sympathy cards in the mail saying, I’m so sorry for your loss—this is ABC News, Fox News, are you interested in getting an interview, and then their business card would be attached. It was so bizarre and disingenuous. I was processing the loss of young friends and what happened to our community and then seeing these people outside that just didn’t care, and who were taking advantage of teenagers. It chipped away at my faith in media and how they’re telling our stories.

So then I wonder if you see the memorial archive as a challenge to the story of the tragedy that was told by traditional news outlets—maybe a parallel record of grief.

It’s a reclamation of our story and a rethinking of the narrative, because there was a lot of the story that was was not told from our perspective. [The memorial archive] is how the community wants to discuss and remember the stories of the people affected—who they were. And we want to talk about the strength we had, and to commemorate those things that happened during that time, which were so powerful.

For me personally, despite what happened during the attack and how we were treated by the media, when I think about how the community reacted, and remember the strength and the love that I felt from classmates, it starts to ease the the complicated feelings of all this, and replenishes faith in humanity and hope in this hopeless situation. I hope that feeling was elicited for others, that they’re remembering the positive things that came out of such an awful situation, and how community members did so much for each other in this time. So I think it is helpful for people still breathing.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.