After decades of steady growth in the prison population in the United States, the number of inmates has, in recent years, finally started to decline. The state and federal prison populations peaked in 2009 with a combined 1.6 million inmates; by 2015, the number of people in the U.S.’s jails, prisons, and parole or probation systems reached its lowest point since 1994. But, according to a new report from the Vera Institute of Justice and the MacArthur Foundation’s Safety and Justice Challenge, this downward trend doesn’t hold true for our nation’s rural jails.

The report finds that, even as populations fall in America’s prisons, the number of people housed in jails—the locally run facilities that hold individuals awaiting trial or sentenced to less than a year—has swelled from 157,000 in 1970 to more than 700,000 in 2015.

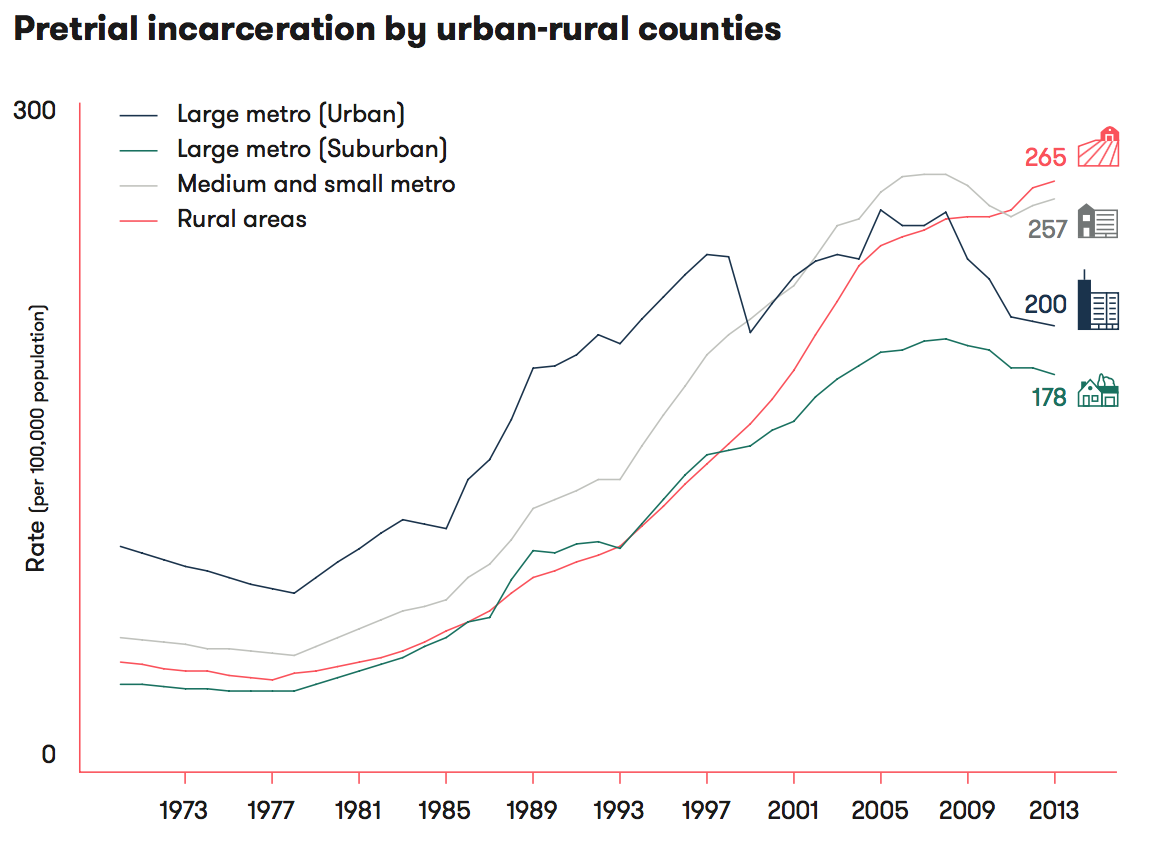

This increase was driven by small, rural counties, the report states, despite the fact that those more isolated communities have much lower crime rates than urban centers.

“Rural counties have been out of sight and out of mind in much of America. We saw this plainly in the last election,” Christian Henrichson, the research director of the Vera Institute of Justice’s Center on Sentencing and Corrections, writes in the report. “In fact, the 2,623 primarily small and rural counties that chose Donald Trump in the 2016 election have more people in their jails and a higher jail incarceration rate than the 489 counties that preferred Hillary Clinton.”

The report finds that these increases are largely due to pre-trial populations. Nationwide, the number of people awaiting trial behind bars was five times higher in 2013 than 1970. Mirroring prison population trends, the number of pre-trial detainees has begun to fall in prisons over the last decade, but the pre-trial population continues to climb in county jails, where the majority (61 percent) of detainees have yet to be convicted.

Most pre-trial detainees are behind bars simply because they can’t afford to post bail. While the bail system ostensibly exists to ensure that defendants show up in court, there is little evidence bail increases defendants’ rate of appearance. Worse yet, pre-trial detention can increase the chances that someone commits another crime in the future; as Jared Keller wrote last year in Pacific Standard, pre-trial detention “creates a carceral system where offenses perpetuate offenses, leading to a permanent underclass of people forever bound to the criminal justice system simply because of their inability to pay.” The Department of Justice itself has called the American bail system unconstitutional. And yet pre-trial populations continue to increase.

While there is little research on rural correctional systems, the new report outlines some hypotheses around what may be driving increases in jail populations. A lack of resources compared to urban areas almost certainly slows down the judicial process, leaving more and more people languishing behind bars as they await trial. Whereas Manhattan’s arraignment courts, for example, are open every day until 1 a.m., rural courts typically follow regular business hours—if they’re open at all; judges in rural areas often cover multiple districts, and thus can only convene proceedings in any one area a few times a month.

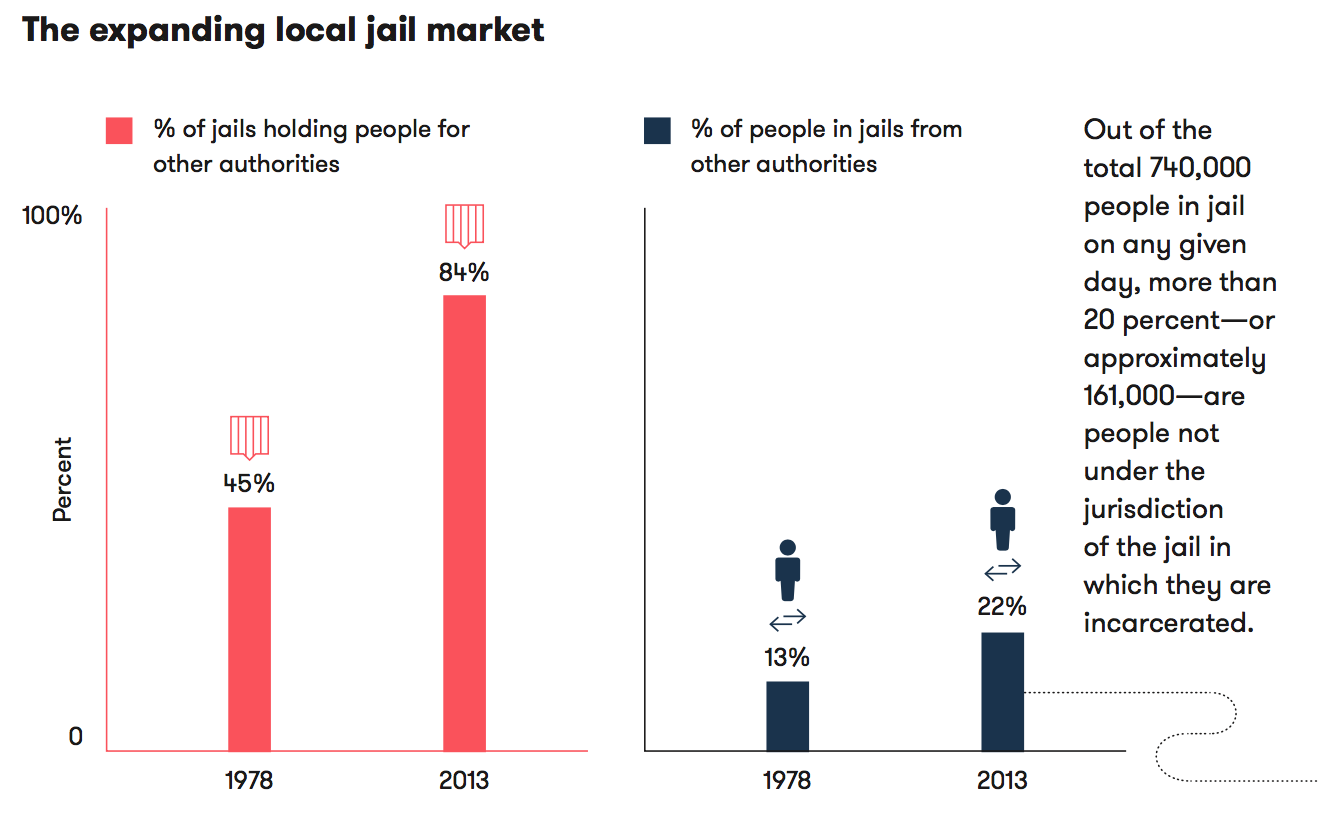

Another reason for increasing jail populations may be what the report calls the “expanding jail-bed market.” Today, 84 percent of U.S. counties hold prisoners for other jails, prisons, or federal agencies such as Immigration and Customs Enforcement. The rate at which rural jails took in inmates for other facilities and agencies increased by 888 percent between 1978 and 2013. These increases were largest in the South and West, where jails acquired large numbers of inmates to help alleviate overcrowding in state prisons.

These inmate overflows are a source of revenue for county jails. Prisons and federal agencies pay upwards of $169 per person to house excess inmates in jails. For some counties in states like Kentucky, Louisiana, and Oklahoma, these per-diem payments are the only thing keeping the facilities solvent. Some jails have even expanded to meet the demand, adding more beds than local needs alone would require.

But the report indicates those extra beds might, in fact, increase jails’ propensity for pre-trial detention. In Grant County, Kentucky, for example, the use of pre-trial detention increased fourfold after the number of jail beds went up from 28 to 300 in the 1990s, according to the report. These expansions can backfire in other ways as well: If state or federal agencies no longer need the jail beds, local taxpayers may wind up footing the bill for the unnecessary expansions.

But for now, at least, the gamble may be worth it; as immigration enforcement ramps up under the Trump administration, demand for jail beds is only expected to increase.