As the president and the White House have been careening from one scandal to the next, Republicans in the Senate have continued to hold discussions on how to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act. In fact, Senators Susan Collins and Bill Cassidy (who co-sponsored a particularly intriguing ACA replacement bill earlier this year) are reportedly also leading bipartisan talks on ACA reform with centrist Democrats like Joe Manchin, Heidi Heitkamp, and Joe Donnelly.

A new report from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a liberal think tank, confirms just what’s at stake in these conversations for a swath of the country that played an awfully big role in getting President Donald Trump elected: rural America. The Affordable Care Act, as it turns out, helped a lot of people in rural areas. For starters, the CBPP report explains, there’s the Medicaid expansions:

Nearly 1.7 million rural Americans have newly gained coverage through the Medicaid expansion. In at least eight expansion states, more than one-third of expansion enrollees live in rural areas: Alaska, Arkansas, Iowa, Kentucky, Montana, New Hampshire, New Mexico, and West Virginia. Moreover, in expansion states overall, rural residents make up a larger share of expansion enrollees than they do of these states’ combined population.

Rural populations also benefited hugely from the ACA’s premium subsidies—over 1.6 million rural Americans got coverage through HealthCare.gov.

As the chart to the left, from the CBPP report, demonstrates, the overall uninsured rate among rural residents declined dramatically after the ACA went into effect, with the biggest drops occurring in Medicaid-expansion states.

All of this is to say, if the American Health Care Act as it’s currently written becomes law (which is unlikely), rural America is in for a world of hurt.

The design of the premium subsidies in the AHCA (they’re flat and are not tied to the cost of insurance in a given area) means that people in high-cost areas (which are disproportionately rural) will receive dramatically smaller premium subsidies than they would have under the ACA.

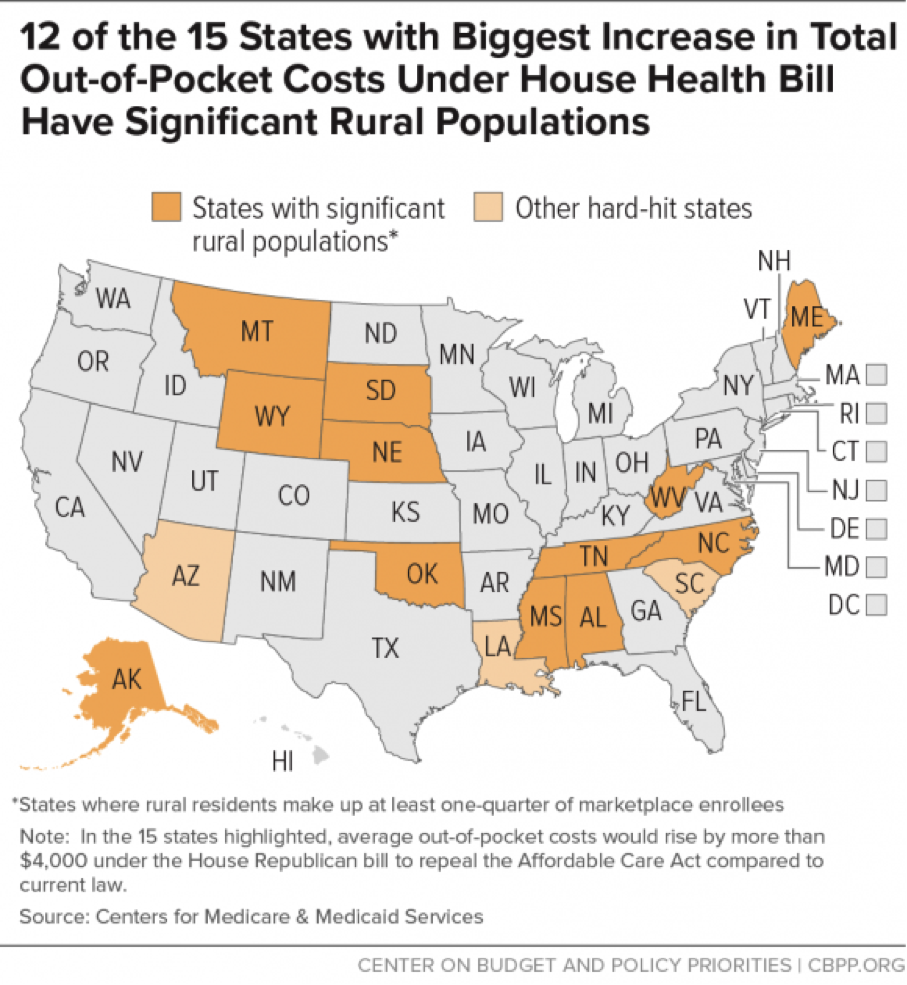

The map below, also from the report, shows the 15 hardest-hit states with respect to rising out-of-pocket costs. Twelve of those states have large rural populations:

But the smaller premium credits aren’t the only disproportionately harmful aspects of the AHCA for rural areas. In addition to potentially reversing coverage gains, the rollback of the Medicaid expansion could seriously jeopardize the financial solvency of rural hospitals, many of which struggle financially and benefited from increases in the percentages of their patients with health insurance. While hospitals serving low-income patients saw financial improvements, no matter their location, after the ACA went into effect, rural hospitals saw larger gains in Medicaid revenues and operating margins than hospitals in more populous areas.

Rural Americans will be particularly vulnerable if states start choosing to opt out of the ACA’s community rating and essential health benefit requirements for a simple reason: Broadly speaking, the residents of those states exhibit poorer health outcomes and so are more likely to benefit from those regulations. Consider, for example, the opioid epidemic that has so devastated many rural communities. Under the ACA, private insurers were required to cover substance use disorder treatment; many addicts also received treatment through Medicaid. But many health-care experts believe insurance companies in “opt-out” states would eventually stop offering plans covering substance use disorder treatment, leaving even insured addicts with few treatment options.

Was this the kind of change rural Americans were hoping for?