Oil and gas drilling in the United States is probably not the main cause of a global spike in heat-trapping methane in the atmosphere since 2007. In fact, methane emissions in the U.S. didn’t increase much at all between 2000 and 2013, according to a new study from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration that analyzed methane levels in air samples collected by NOAA aircraft around the country.

Atmospheric researchers say accurately measuring methane as required under the Paris climate agreement remains challenging and requires more frequent, regular sampling, as well as more satellite observations and international scientific cooperation.

The latest findings contrast with a study from just last year that suggested U.S. methane emissions from oil and gas production had been increasing at a rate of 20 percent annually. New analyses of methane’s chemical signatures suggest the spike in global methane readings since 2007 comes from agriculture and other organic sources mainly in the tropics, rather than from oil and gas production. Global warming is speeding up the metabolism of microbes that produce methane as they digest dead plants.

Cutting methane emissions is a cost-effective way for countries to cut greenhouse gas pollution in the short-term, while working on long-term goals to limit CO2.

Wildfire emissions are also a factor, and, in the last few years, scientists have identified freshwater reservoirs as big methane sources; changing water levels flood large areas of vegetation, which in turn produce methane and other greenhouse gases as they decompose. (Scientists can distinguish these sources of methane emissions by studying the ratios of various isotopes associated with different sources.)

The level of methane emissions from oil and gas production in the U.S. has implications for the Paris climate agreement’s target of limiting global warming to less than two degrees Celsius, as well as for the nation’s energy policies, which during the Trump administration are expected to favor continued use of fossil fuels, including natural gas. Domestic fracking and oil drilling may not be the main cause of the recent sharp increase in global methane levels, but, overall, they’re still a significant source.

NOAA scientist Lori Bruhwiler, who led the international team of researchers in the new study, says they couldn’t find any evidence of a surge in methane from U.S. oil and gas. Pinpointing emission sources is important in the context of short-term climate goals.

“The Paris Agreement asks us to look at emissions every five years. This study shows we need to measure much more frequently. If we want to keep close tabs on emissions within a five-year period, we have to invest in more sampling,” Bruhwiler says.

Under President Barack Obama, the U.S. was one of very few countries in the world to announce a goal for limiting methane from oil and gas, aggressively shooting for a 40 to 45 percent reduction from 2012 levels by 2025. If all the world’s major methane-emitting countries implemented similar goals for the next 20 years, it would result in cutting emissions equivalent to shutting down all coal-burning power plants in India and the European Union, according to an analysis by the Natural Resources Defense Council. But the Trump administration is moving in the opposite direction by trying to end efforts to track, report, and cap methane emissions.

The new study, published March 24th in the journal Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, is one of the latest and most sophisticated attempts to measure methane sources precisely. Knowing where it’s coming from is the first step in controlling it.

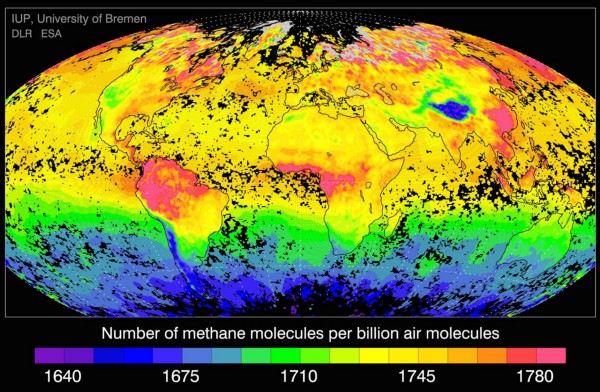

It’s hard to track methane because it comes from so many sources. It also mixes well with other gases in the atmosphere and is easily transported across continents and oceans.

Because the world is already close to busting the greenhouse gas budget to cap global warming, the estimated 29 million metric tons of methane generated by U.S. oil and gas production matter a lot. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, methane makes up about 11 percent of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions.

Measurements taken from planes, satellites, and on the ground near oil and gas facilities show that methane hot-spots are associated with natural gas production. In August of 2016, NASA released a study about the methane hot-spot in the southwestern U.S. near the Four Corners area. The agency’s analysis was able to identify and measure more than 250 individual sources of methane, finding that about 25 of those sources were emitting about half the total methane in the region.

Findings like those suggest that it might be possible to control methane emissions from fossil fuel processing. But it’s also clear from the massive Aliso Canyon leak in California, first discovered in October of 2015, that there are chances of disastrous leaks from large natural gas facilities. The Environmental Defense Fund estimated that the amount of methane leaked at Aliso Canyon had the same 20-year climate impact as burning nearly a billion gallons of gasoline.

Small leaks can also add up. In 2015, engineers and atmospheric researchers found up to 15 billion cubic feet of natural gas, worth some $90 million, may be escaping from leaky pipes in the Boston area.

Since methane is so powerful and fast-acting, it’s a major climate problem. Cutting methane emissions can be a cost-effective way for countries to cut greenhouse gas pollution in the short-term, while working on long-term goals to limit CO2.