In honor of International Day of Forests, a look at the trees that need our help the most.

By Bob Berwyn

Hail coats the ground in a stand of ancient bristlecone pines in the Mt. Goliath Natural Area, part of the Arapaho National Forest, about 40 miles west of Denver, Colorado. (Photo: Bob Berwyn)

Twisted, lightning-scarred and windswept, North America’s ancient bristlecone pines have seen as much climate change as any living organism on Earth. The oldest of the giants, growing in the remote White Mountains of eastern California, sprouted from seed more than 5,000 years ago, about the same time recorded history began with Sumerian culture. After persisting and co-existing with humanity for all that time, it’s not clear how much longer bristlecone pines will be able to survive. Despite their longevity, they appear to be among the tree species most vulnerable to extinction.

There aren’t that many bristlecone pines to begin with, and global warming is further squeezing those that have survived. Bristlecones only grow in a narrow elevation band near the treeline. As temperatures increase, they are likely to be pushed off the mountain tops. At the same time, warmer conditions have enabled tree-killing bark beetles to spread upward into their high mountain realm.

Even the beech forests of Europe, in a historically cool and moist climate, are susceptible to the effects of global warming,

according to University of Stirling researchers

. (Photo: Bob Berwyn)

Bristlecones aren’t the only species that will be hurt by the build-up of greenhouse gas pollution. There are clear signs that forests all over the world are feeling the heat of climate change. Scientists with Australia National University recently documented that the world’s oldest and biggest trees are dying in disproportionate numbers. According to a 2014 United States Geological Survey study, the biggest and oldest trees are the ones that sequester the most carbon.

Trees may be one of our last best hopes to limit global warming, a fact that’s worth remembering today as the United Nations celebrates the International Day of Forests. U.S. forests offset about 11 percent of carbon emissions in 2015 (the most recent year with data), according to the Environmental Protection Agency. Globally, as much as 45 percent of the carbon stored on land is tied up in forests, according to NASA. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says that good forest conservation and intensive planting of new forests could be one of the most effective tools to remove heat-trapping CO2 from the atmosphere.

Dylan Berwyn enjoys a view across thousands of acres of forest from atop a centuries-old Douglas fir in Dillon, Colorado. Nearby trees of the same species, 300 years old, have helped climate scientists track changes in climate during the past centuries. The view across Dillon Reservoir encompasses Peak 1 in the Tenmile Range, where entire mountainsides of lodgepole pines were wiped out by swarms of mountain pine beetles multiplying in an ever-warmer climate. (Photos: Bob Berwyn)

There are simple steps everyday citizens can take to help combat, at least to some degree, the negative effects of climate change.Urban forests are an important part of climate mitigation, and many cities offer the opportunity to participate in programs like Arbor Day (April 28th), when community tree planting is fostered. University extension services are active in promoting forestry and tree planting in nearly every state, and the U.S. Forest Service also has plenty of opportunities for volunteers to get involved.

With money and resources depleting, scientists around the world are increasingly turning to citizens for help in monitoring forests. In Austria, for example, forest managers are asking citizens for help identify trees that may have a genetic resistance to a pathogenic fungus that is on the verge of wiping out economically important ash forests. Those finds may help re-establish ash trees for the future.

From fast-growing Florida bamboo, a viable source of renewable resources, to ancient oaks in Tierra del Fuego, forests are critical to the global environment. (Photos: Bob Berwyn)

A shoreline grove of mangroves near Belize City. (Photo: Bob Berwyn)

We mostly think of forests as land-based, but along tropical and subtropical shorelines worldwide there are huge swaths of mangroves, which are increasingly seen as key areas for storing carbon. University of Maryland scientists estimated in a recent paper that mangrove forests capture and store as much as 34 million metric tons of carbon annually, about equal to the carbon emitted by 26 million passenger cars in a year.

The often sympbiotic relationship of trees and fungi is on display, with

mycorrhizzal species of mushrooms whose underground mycelium intertwine with tree roots, protecting them from pathogens and enabling a crucial nutrient exchange. Many tree species don’t grow well or at all if their complementary fungi are not present, and there is some concern in Colorado that climate change and the pine beetle epidemic have combined to

. (Photos: Bob Berwyn)

Left: Tiny cup lichen of the Cladonia family grow on a stump. The lichen are a primary food source for forest grazers like deer and caribo. In northern boreal forests, the lichens are economically important for indigenous people like the Sami. Some species contain antibiotic compounds that can be extracted for a cream.

(Photo: Bob Berwyn)

| Right: A pine warbler takes shelter from the rain in a Colorado aspen grove. Forests are home to about

80 percent of the planet’s terrestrial biodiversity

, including vast numbers of birds.

(Photo: Bob Berwyn)

Stands of spruce encased in frozen fog in the Snake River valley of Summit County, Colorado. Forests are key parts of the global water cycle. Their root systems attenuate runoff and pull moisture from the earth, transpiring it back into the sky. Scientists now know that, as they breathe, they also generate tiny particles of aerosols that serve as seeds for clouds and precipitation in the atmosphere.

(Photo: Bob Berwyn)

Scientists are increasingly sounding warnings of a global forest health crisis. Some scientists say bark beetles are on the rise in Europe. Other research suggests that harmful tree-killing fungi could proliferate in a warming world, and one very recent study says forests worldwide are increasingly facing a dire threat from drought.

A pair of Douglas fir trees seem to dance with each other near Ute Pass, in the Colorado Rocky Mountains, while a dead fir in the same area stands as a monumental testament to the wonder of trees.

(Photos: Bob Berwyn)

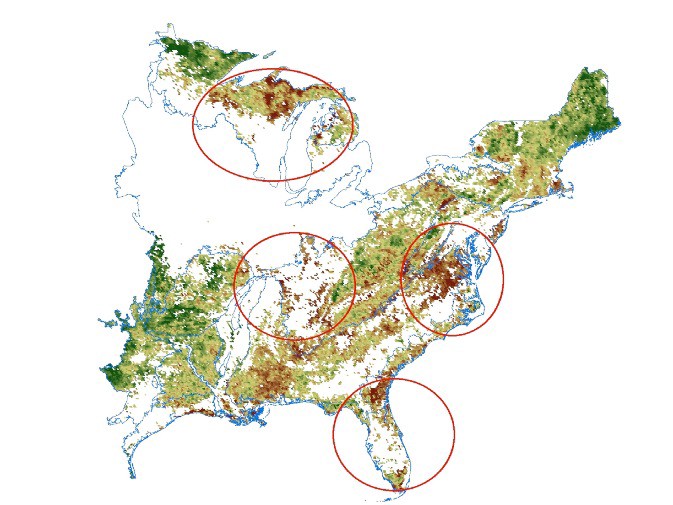

Armed with satellite data, NASA researchers say that warmer temperatures and changes in precipitation have resulted in a significant decline in forest canopy cover in the U.S. The changes were most striking in the mid-Atlantic region, where the researchers estimate that 40 percent of forests have been affected.

Trends in forest canopy green cover over the Eastern United States from 2000 to 2010 derived from NASA MODIS satellite sensor data. Green shades indicate a positive trend of increasing growing season green cover, whereas brown shades indicate a negative trend of decreasing growing season green cover. Four forest sub-regions of interest are outlined in red, north to south as: Great Lakes, Southern Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic, and southeastern Coastal Plain.

(Image: NASA)

Clockwise from top left: A healthy spruce forest landscape near Vail, Colorado; nearly every mature spruce has been killed by spruce beetle in this drainage on the Rio Grande National Forest. The spruce beetles have spread across three million acres in the past five years and the infestation shows no signs of slowing down; near Frisco, Colorado, stands of red and dead lodgepole pines show the effect of climate change, with more dead and dying trees visible in mountainside forests near Ouray, Colorado.

(Photos: Bob Berwyn)

Huge tracts of lodgepole pines on the White River National Forest in Colorado were killed by mountain pine beetles in the early 2000s during a time when average temperatures increased markedly and there was a sustained absence of winter cold snaps, which during previous outbreaks had served to check the population of the insects. In this Summit County scene, dead forests are visible as reddish areas on the flanks of the mountains above Dillon Reservoir. (Photo: Bob Berwyn)

Triggered by warming temperatures and a sharp drought in 2002, mountain pine beetles wiped out nearly four million acres of trees in Colorado and Wyoming in a span of only 10 years, the largest such outbreak that researchers could identify going back thousands of years to when the glaciers of the last ice age retreated and forests started to colonize the Rocky Mountains.

The sudden forest death in the heart of the Rockies is a warning sign for other forests, and time is short. The pine beetles kept multiplying because warmer temperatures speed up their metabolism. Longer summers mean they now breed twice a year instead of just once. And there have been no cold snaps severe enough to kill the beetle larvae for several decades. More of them survive the winter, so they have a head start on breeding the following summer.

It was a landscape-level change so vast and fast that people in the region suddenly felt a direct effect from climate change, and that effect will linger for future generations, as global warming limits forest regrowth in areas near Colorado cities, whose residents need those forests to maintain healthy drinking water supplies, as well as for recreation.

There are secondary effects from the beetle-kill, including big changes in the snow melts and water runs off the mountains. Winter and spring floods have become more common. Without trees to drink up the water (remember, we’re talking about four million acres of dead forest), streams also flowed higher later in the season than ever previously recorded. And, in beetle-killed areas that burned, sediment runoff led to huge challenges for maintaining water quality.

There’s also a good chance the big expanses of dead forest can change weather on a local scale, according to climate researchers who tracked changes in thunderstorm activity in Africa. They found that deforestation on the slopes of Kilimanjaro had a distinct effect on precipitation, and large-scale forest die-offs in other regions could have similar consequences, scientists warn.

In the age of global warming, with record CO2 levels in the atmosphere, it may be hard to see the forest for all the trees. But every tree counts—just one mature oak or pine can absorb 48 pounds of carbon each year. A massive effort to protect forests and plant more trees is one of the ways society can protect itself from a worst-case climate scenario.

The jury still appears to be out on how climate change will affect California’s giant coastal redwoods, like the 200-foot specimen in Muir Woods, near Sausalito, but fire researchers say that Florida’s oak-palmetto scrub forests (right) are definitely at risk from increasing temperatures.

(Photos: Bob Berwyn)