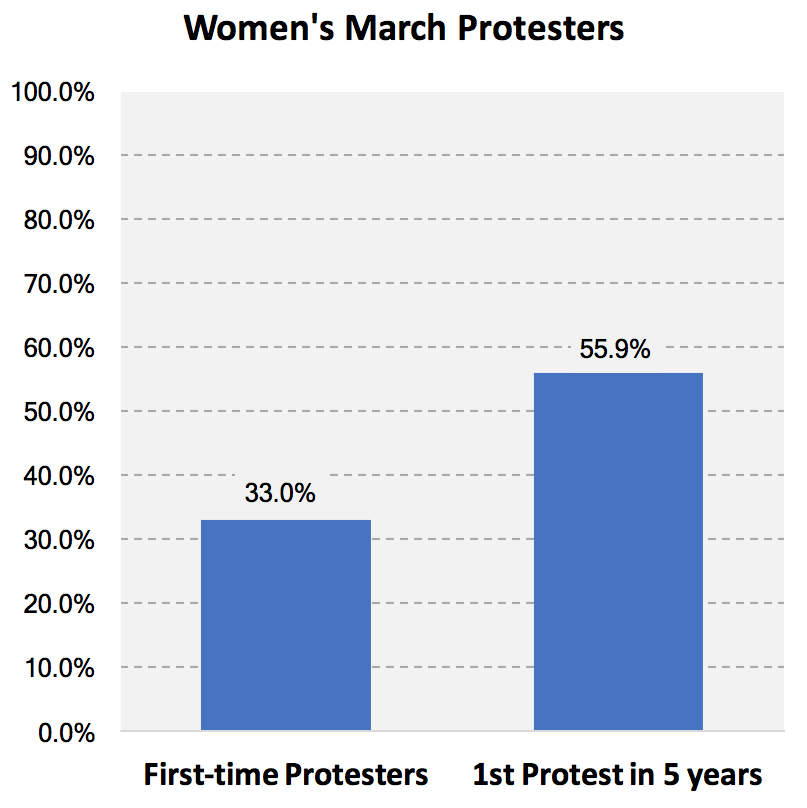

One-third of the participants reported that the Women’s March on Washington was their first time participating in a protest ever.

By Dawn M. Dow, Dana R. Fisher & Rashawn Ray

Protesters walk during the Women’s March on Washington, with the U.S. Capitol in the background, on January 21st, 2017. (Photo: Mario Tama/Getty Images)

Waves of pink knitted hats and protest signs packed the streets of Washington, D.C., on January 21st, 2017, just one day after President Donald Trump’s inauguration drew average crowds. The Women’s March of 2017 was the largest protest in recent history, bringing together over 500,000 people in D.C.—the location of the flagship march—and over 2.9 million people nationwide. Protesters came from near and far to protect a diverse set of rights that are threatened by the incoming administration.

Perhaps the Women’s March can be understood as a partial response to President Barack Obama’s declaration in his farewell address that the most important office in a democracy is “citizen,” and, thus, citizens must work to improve our society, not just when there is an election or when their own narrow interests are at stake. The march was an example of what this kind of democracy looks like. Originally proposed on social media, the idea for the march took off and a groundswell of support emerged from independent individuals and those associated with organizations. Despite this level of support, many have speculated about who attended the march, whether they voted, the goals of protesters, and their level of civic engagement. Some have discounted the protesters as only forwarding the perspectives and issues of white women and eschewing those of other groups such as people of color and/or members of the LGBTQ community.

Combating this new era of “alternative facts,” a research team led by Dana R. Fisher, Dawn M. Dow, and Rashawn Ray from the University of Maryland–College Park provides data-supported facts about participants at the Women’s March. Teams of two surveyed participants throughout the march to understand who was protesting and why. In total, 527 people completed the survey (representing a 92.5 percent response rate).

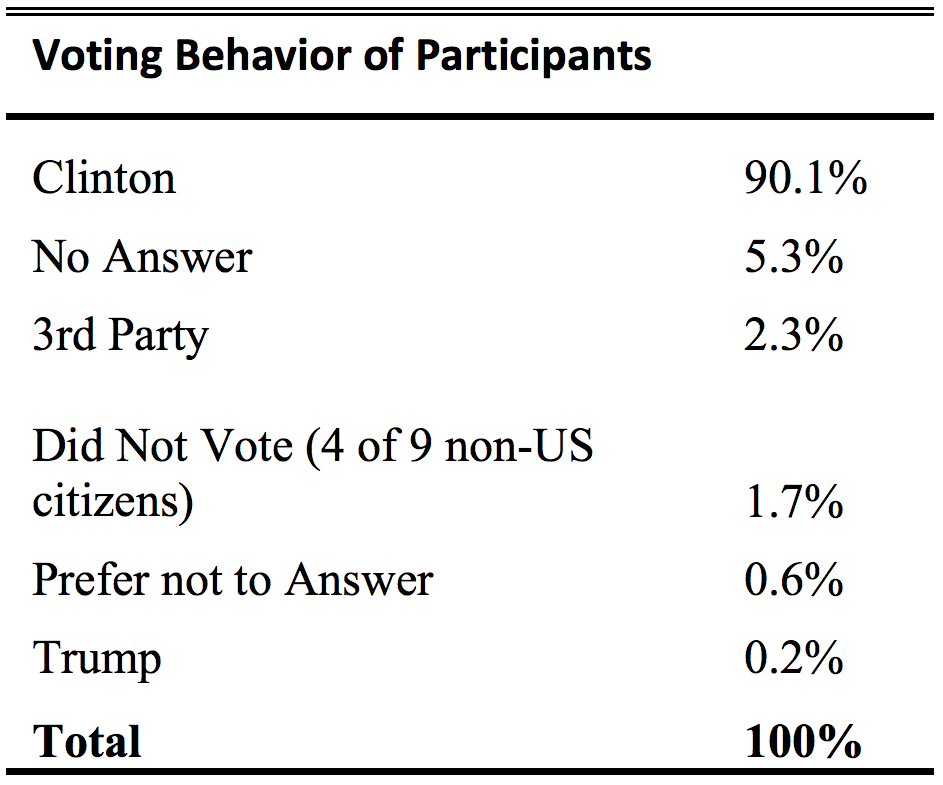

Far from using protesting as a substitute for voting, as a recent tweet from Trump suggested, initial findings from this project show that the protesters at the Women’s March voted, and overwhelmingly for Hillary Clinton. Among respondents, 90.1 percent reported voting for Clinton, 2.3 percent voted for a third-party candidate, and 0.2 percent (one person) voted for Trump. Among the 1.7 percent who explicitly said they did not vote, nearly half were non-United States citizens who are not eligible to do so.

Our findings also suggest that the Women’s March has potentially lit the political fires of a new generation of activists and reactivated the political activism of others. Indeed, one-third of the participants reported that the Women’s March was their first time participating in a protest ever. For over half of the participants (55.9 percent), the March was their first protest in five years (including those who had never participated before).

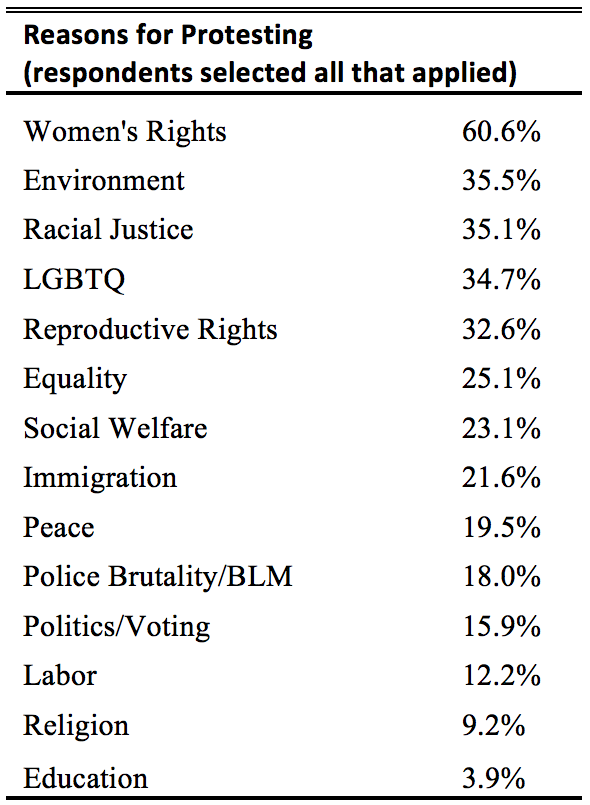

Respondents were also asked to identify the issues that motivated them to protest. Our data suggests protesters were unified by a range of distinct and overlapping priorities. Given the name of the march, it is not surprising that 60.6 percent of respondents cited women’s rights as a motivation for protesting. However, other social issues were also at the forefront of protesters’ minds. Nearly tied for second place, protesters cited the environment (35.5 percent), racial justice (35.1 percent), LGBTQ rights (34.7 percent), and reproductive rights (32.7 percent) as motivations to attend. Other political issues were also well represented including equality (25.1 percent), social welfare (23.1 percent), and immigration (21.6 percent). Indeed, rather than representing a narrow set of interests, protesters identified multiple and diverse motivations for participating.

Historically, protests focus on one social issue such as equal pay, climate change, voting rights, or same-sex marriage. The Women’s March was different in that its protesters were seemingly engaged in intersectional activism—a version of activism that is sensitive to how race, class, gender, and sexuality complicate inequality. Perhaps the Women’s March is distinct in this way because protesters were not just motivated by concrete issues, but they were also motivated by a desire to protect and reassert a vision of America that embraces diversity and inclusion as a strength rather than a threat. This vision of America is increasingly under attack by the Trump administration. It remains to be seen how the energy from the march will translate into change locally across the country, but recent protests suggest that citizens stand ready to protect their rights and the rights of others.

This story originally appeared on Sociological Images, a Pacific Standard partner site, as “This Is What Democracy Looks Like!”