Despite the ceaseless march of mass extinction, some species are still making a comeback.

By Jimmy Tobias

Grey wolf pups in Jackson County in southwestern Oregon. OR7, originally from the Imnaha wolf pack of northeastern Oregon, is believed to be the pup’s father pending DNA samples. (Photo: Public Domain)

In the last three weeks alone, we learned that the world has recently lost roughly 40 percent of its giraffe population and that scientists now consider the species vulnerable to extinction. We learned that 20 of the 72 shark and ray species that live in the Mediterranean Sea are critically endangered due to overfishing. The International Union for Conservation of Nature, meanwhile, added 13 previously unrecognized bird species to its list of extinct animals. And the New York Review of Books published an essay reminding us that “46 common land-bird species in North America have lost half or more of their populations — a net loss of 1.5 billion breeding birds — since 1970.”

For those who are paying attention, the mass extinction crisis — a slow drip of scandalous news about the annihilation of living organisms — can be numbing. It’s hard to wrap one’s head, much less one’s heart, around the scope of the catastrophe. Numbness, though, is not what this moment requires. Hopeful stories help cut through the anesthetizing fog of loss, and California wildlife officials just offered us a good one. It’s the story of a local victory that matters.

On December 6th, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife released its final conservation plan for the gray wolves that are slowly but surely re-establishing themselves in the state. The return of these magnificent predators is the result of visionary long-term conservation work, and California’s new plan is a sure sign that wolves will be accepted and protected within its borders.

“This is historic wolf habitat so we are not going to try to push them out,” says Jordan Traverso, a spokesperson for the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, or CDFW. “It is an exciting story because [the wolves] have returned after almost 100 years” of absence.

OR7 photographed in Jackson County, Oregon, in May 2014. (Photo: Public Domain)

Wolves were extirpated from California in 1924, when the state’s last-known individual was trapped and killed in the mountainous north. Californians didn’t see the species again until 2011, the year a lone wolf named OR7 ventured into the state from Oregon. OR7 didn’t stay, but, last summer, the CDFW announced that two adult wolves and five pups had taken up residence in Siskiyou County. The Shasta pack, as it is known, has since been joined by a second breeding pair that is living in Lassen County. Wildlife officials believe all nine of these animals are likely descended from the wolves that the United States Fish and Wildlife Service famously reintroduced to the Rocky Mountains in the mid-1990s.

Ever since OR7 set his paws on California soil, state authorities have been preparing for a more robust wolf presence in the state. Beginning in 2012, CDFW convened a working group made up of ranching interests, big game hunters, and environmentalists to develop a conservation plan for the predators. After dozens of meetings between stakeholders and a thorough public scoping process, the plan was finalized this month. According to Pamela Flick, a California-based staffer with Defenders of Wildlife, it “could very well be the best state wolf conservation plan that is on the books anywhere in the United States.”

“The [CDFW] plan is a welcome mat for wolves,” Flick adds. “It is saying: Come to California, we have a plan to conserve your species as you return to the landscape.”

Among other things, the plan puts forward proactive and non-lethal methods for preventing conflicts between livestock grazers and wolves. It describes the legal status of the species, which is protected under both federal and state endangered species statutes. It also identifies key habitat restoration initiatives and lays out an implementation strategy that will help the new wolf population thrive.

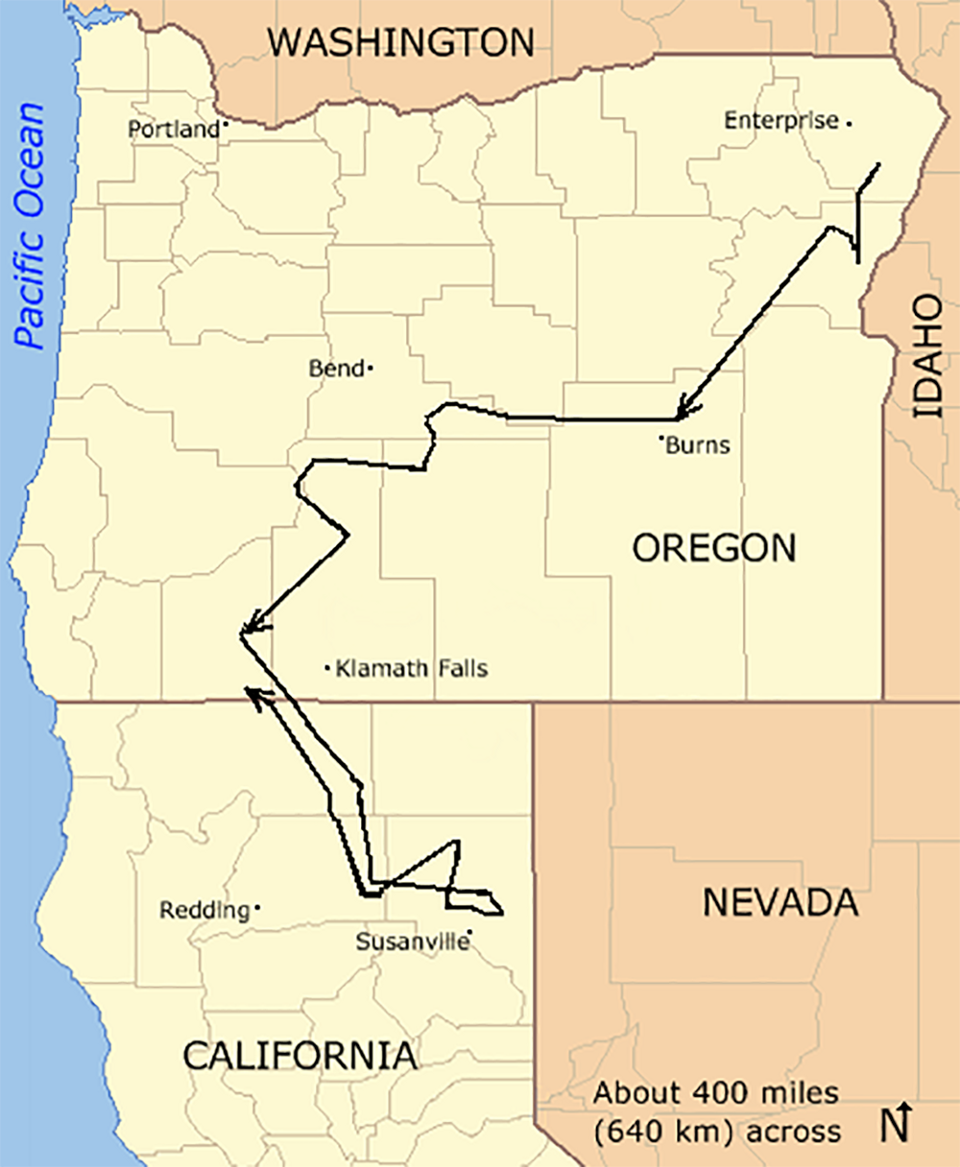

Approximate route of OR7 between September of 2011 and March of 2012. (Map: Finetooth/Orygun/Ruhrfisch/Wikimedia Commons)

And though none of the various stakeholders got everything they wanted in the plan, its collaborative nature helped avoid the political strife that so often surrounds wolf conservation and management.

“I am very appreciative of the process that the department went through in crafting that plan,” says Kirk Wilbur, government affairs director for the California Cattlemen’s Association. “It was very inclusive and even when [CDFW] came down on a side of an issue that we disagreed with we still felt that our voice was being heard.”

The return of the wolf to California reminds us that some wildlife losses need not be permanent. As long as they survive somewhere, as long as we’re willing to help bring them home or at least leave them alone, wild creaturescan make a comeback.

In her beautifully useful book, Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities, Rebecca Solnit writes that the restoration of species, whether wolves in the West or salmon in the Columbia River or bison on the Great Plains, contributes to “a future with room in it for some kind of wildness.” As one of the most conservation-averse administrations in history prepares to take power, as extinction casualties mount, that wild future needs our unrelenting commitment come what may.