Since the election of President Donald Trump, there’s been a lot of talk about how demographic changes, and the prospect of racial equality, have left his strongest supporters fearful of losing “their” America—which they see as, by rights, a largely white nation.

Yet commentators have paid less attention to the fact that many white American liberals harbor some of these same racial fears: a fear of not being part of the majority, and a fear of losing the privileges they were born with.

Fundamentally racist ideals are not the exclusive province of the right. A Reuters poll during the 2016 election found that over 30 percent of Trump voters believed black people to be less intelligent than white people. But the same poll found that over 20 percent of Hillary Clinton voters felt the same way.

Racism can be found across the political spectrum, and there is a long history of white liberals preaching equality while being reluctant to fully embrace efforts to make society more equal in ways that might discomfit them even a little. People born with privilege and power are often squeamish about giving any of it away.

Joe Feagin, distinguished professor in sociology at Texas A&M University, says that white liberals are “good on certain racial issues” but often don’t put a lot of action behind their words, or don’t go as far as they could to make racial equality a reality.

Feagin recounts a story about President Lyndon B. Johnson that illustrates his point. Johnson was responsible for getting three major civil rights laws passed during his presidency but was still leery of fully embracing the fight for equality.

During the 1968 presidential campaign, while Johnson was still in the race, he created what was called the Kerner Commission to investigate why black Americans were rioting in cities around the country. In the end, the commission concluded that poverty and white racism were the causes. Upon seeing the results of his own commission, Johnson backed away from its report and even aspersed its findings.

“That was the only commission in U.S. history which used language about white racism being the problem with race in this country,” Feagin says. “Johnson saw the report and knew it was political dynamite during his 1968 run for president and backed off and attacked his own commission.”

When it came down to it, Johnson prioritized the delicate feelings of white Americans over the needs of black Americans. He chose to appease white voters rather than confront the monumental problem of systemic racism.

This isn’t ancient history, though. Many modern politicians have a history of failing to support racial equality.

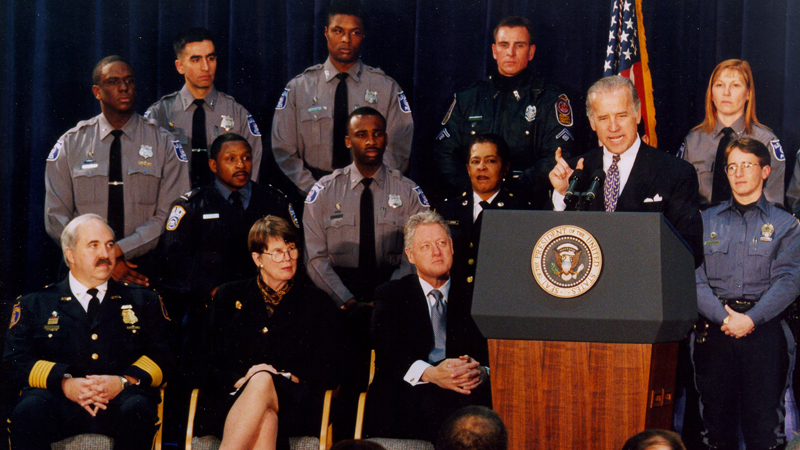

Former Vice President Joe Biden—now a presidential candidate for 2020—fought against racial integration efforts in the 1970s. Between 1973 and 1975, Biden regularly voted for proposals that aimed to prevent school districts from busing white and black students to different neighborhoods to create schools that were more equally mixed.

“[Biden] claimed he was in support of school integration, though he was anti-busing,” says Jason Sokol, an associate professor of history at the University of New Hampshire. “He opposed the means that would achieve the end of school integration.” Sokol says Biden did so because he feared losing the support of white Democrats, who largely opposed these desegregation proposals.

In the 1990s, the Clinton administration helped pass a crime bill that many critics argue disproportionately targeted people of color and contributed to America’s ongoing mass incarceration problem. Clinton signed the law at least in part to appeal to white voters afraid of minorities. Critics have also argued that the welfare reforms passed during the Clinton years were similarly based on the era’s racist sentiments, and have disproportionately harmed people of color. (This historical baggage inevitably became something 2016 presidential candidate Clinton had to address during her campaign, and she eventually said that parts of the crime bill had been “a mistake.”)

(Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Over the past half-century, liberals have fought for racial equality and inclusivity on some occasions while standing in its way on others. Feagin argues that the reason for this apparent inconsistency is that white liberals often prefer to address racial inequality at a slow pace, in an effort to maintain something fairly close to the comfortable status quo.

Further, Feagin says, many liberals often only want to address racism when they see a personal benefit to doing so.

“Once people get wealth and privilege, at least a majority of them don’t want to give it up unless they can see a good reason for it,” Feagin says. “The ‘good’ reason has to include their own self-interests.”

Feagin points out that in the 1950s and early ’60s, while the U.S. was in the midst of both the Cold War and the Jim Crow era, Soviets often used racial strife in the States for their international propaganda efforts. He recounts that when dogs were biting demonstrators in Birmingham, Alabama, in the summer of 1963, the Soviet Union “made thousands of photos [of the incidents] available across the planet.” Essentially, the racial struggles in the South were giving the U.S. government a bad image internationally. In response, Feagin says, the moderate to the liberal wing of the white male elite started to turn against segregation.

“The U.S. State Department, which had been fairly conservative, started issuing memos to the Supreme Court supporting school desegregation and supporting ending racial segregation in the South,” Feagin says.

This style of treating racial justice as a political rather than moral calculation is still in vogue today. Feagin says that contemporary white Democratic candidates will often push for policies that will increase racial equality, but only so far as white moderates and white conservatives will let them. He says such politicians often attempt to weigh what voters of color want against what white people currently think is an acceptable amount of change in the power balance.

“There’s a fair amount of support right now for going ahead with a federal commission to study reparations for black Americans, but it’s one thing to appoint a commission, and it’s another thing to actually support legislation and work for it,” Feagin says. He adds that, in the 2020 campaign, white candidates will likely dance around certain racial-justice issues that white Americans see as radical.

White Americans on the left and right often fear full racial equality and demographic change because of an implicit desire to maintain their present advantages.

(Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

“On some level, we all want to belong to groups that confer advantage and give us a sense of stability and certainty; this seems to be part of human nature,” says Eric Knowles, associate professor of psychology at New York University. “And, in fact, studies suggest that white Americans from across the political spectrum may feel threatened by the prospect of becoming a minority.”

Christopher Parker, professor of political science at the University of Washington, says that, while conservative whites are more sensitive to a perceived loss of power, many liberals also worry about it. “Insights from behavioral economics suggest that most people, regardless of political orientation, are sensitive to perceived losses,” Parker says.

In polls, you’ll find that white Americans of all backgrounds often voice concerns about possibly being discriminated against if they are no longer part of the ethnic majority. This concern would suggest that white Americans are aware on some level of how oppressive the white majority has been against people of color.

Yet Feagin says his research has not found that people of color actually have any desire for the kind of retribution that white Americans so fear.

“When we conceive of ethnic ‘others’ as a monolithic bloc, we tend to develop almost paranoiac theories about their intentions,” Knowles says.

There is also evidence that white Americans who oppose things like affirmative action are often against it not merely out of self-interest, but also because they’re concerned with protecting the interests of other whites.

“Many white liberals might support affirmative action in the abstract, but worry that such programs contradict their own sense of meritocracy and might harm their own children’s chances of getting into a good college,” says Lily Geismer, associate professor of history at Claremont McKenna College.

This fear gets to the core of the hypocrisy of many white liberals. In the abstract, white liberals will say they want equality, but when things get specific, they’re sometimes worried about losing what they’ve been handed, and especially about being treated as badly as minorities in America have been treated in the past.

Elijah Anderson, professor of sociology and African-American studies at Yale University, says that people on the left and people on the right often share the same fears when it comes to racial equality and demographic changes.

“It’s a human issue,” Anderson says. “It’s not a political issue whether you feel the fear; it’s a political issue when you try to think about doing something about it.”

In a piece for Vox last year, Anderson pointed out that white people of all backgrounds often feel uncomfortable with seeing people of color in “white spaces,” whether they realize it or not, from neighborhoods to business settings. We may have pushed desegregation in our laws, but it’s clear many white Americans still haven’t fully embraced a desegregated society in their minds.

While many Trump supporters and other white conservatives who hold similar ideals will explicitly oppose efforts to make society more racially equal and inclusive, many white liberals show more implicit biases that can harm efforts to achieve these goals. This does not mean that both sides are equally guilty when it comes to stalling such efforts, but it means that many of the people ostensibly fighting for anti-racist policies have some introspection to do. An ally is only as useful as their investment in the cause.

Pacific Standard’s Ideas section is your destination for idea-driven features, voracious culture coverage, sharp opinion, and enlightening conversation. Help us shape our ongoing coverage by responding to a short reader survey.