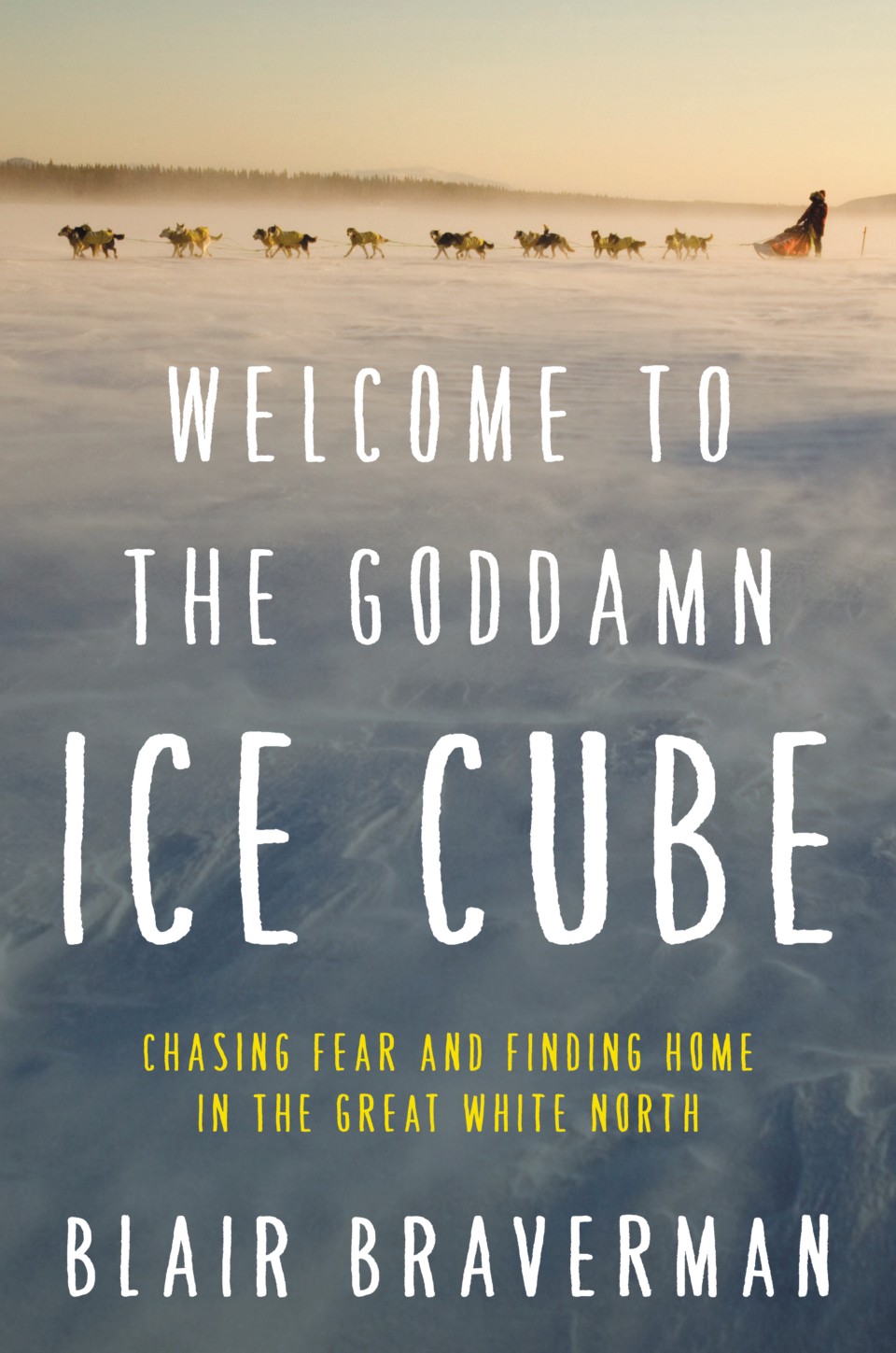

In July, Blair Braverman released Welcome to the Goddamn Ice Cube, a memoir/ethnography hybrid about her travels around the Arctic in her late teens and early 20s. Set in what many consider harsh settings—a glacier in Alaska and a tiny village 200 miles above the Arctic Circle in Norway—the book traces Braverman’s experience as a young woman living alone in two very different communities, both of them dominated by men.

I’ve known Braverman since 2007. She was actually a student in one of my writing classes at Colby College in Waterville, Maine. Recently, she returned to campus to give a reading of Welcome to the Goddamn Ice Cube and speak with students. During her visit, we sat down and talked about some of the issues of writing stories set in Northern landscapes.

So we have these artificial neutrals when we think about writing the American experience, and they are generally white and male, an endless number of adventure stories that are simply accepted as not being redundant. What’s your experience been like, pushing into this territory?

There are things that are considered neutral in the American literary world that are not actually neutral; we’ve just agreed upon them, or had them forced upon us. The Arctic isn’t neutral. Anything set there is going to be “about” landscape or environment or culture in a way that’s not true for stories set in Boston. And that’s the same thing if you’re a writer of color or disabled or in any way not white, male, straight, Christian — your writing is automatically that many degrees away from what we’ve agreed is mainstream. A book by a woman about her experiences is going to be “about” gender in a way that a man’s book is not considered to be about gender even though that’s always there.

There starts to be filters about how much of it can become popular or be published at once. If you’re sending out a book that takes place in the Arctic—a book about science, for example—but there has recently been a book set in Anchorage, publishers are going to say “hey we did an Alaska book,” even though the books have absolutely nothing to do with each other beyond that landscape in the background.

Or, “we did an Alaska book by a woman last year….”

Exactly. The more “ticks” you have on that checklist, the less room there is for you to have a story that seems like it might overlap in the market with someone else’s.

But there’s endless room for Alaska or Arctic adventure narratives by men, as we see with Barry Lopez, John McPhee, Joe McGuinness, Seth Kantner, Nick Jans, James Campbell, and so on.

I don’t know if it’s endless, but there’s definitely more space for it, because white men writing about the Arctic are only one degree away from that neutral. But if you have, say, an older Jewish woman of color writing about the same adventure, it’s going to be an outsider narrative and assumed to have a limited audience based on the author’s own demographics. Or else it’s the exception that proves the rule. Eli Clare comes to mind as a writer who straddles multiple subcategories. He’s disabled, queer, trans, rural, and writes about the environment. He’s brilliant, but the literary world doesn’t know what to do with him.

Maybe one of the issues is that people have this idea of the Arctic as being clean and pure, and when women write about it, we’re talking about some of the harsh realities, like violence, poverty, and sexism.

It’s an ideal of purity, because people have never been there. Part of that, I think, is deep racism, associations with whiteness. Also, the Arctic doesn’t have many bugs.

(Photo: HarperCollins Publishers)

You first went to Alaska as a teenager, and lived on a glacier for two summers. How did that impact your sense of self?

Nobody—human or animal—is supposed to live on a glacier. There was this real insecurity, people trying to prove they had a right to be there, that they were tough or worthy or competent enough to belong. As a teenager coming into a community of older men, it didn’t occur to me that their insecurities could rival my own. I was failing at a rigged game, and I tried to prove myself in ways that weren’t healthy, mainly by ignoring my body.

You say in your book that when you look back and break it down, it was one long competition.

Yeah and if you’re insecure about your ability to belong in a place, you improve your own status by finding someone who belongs there less than you and continually insult and denigrate and diminish them, which is exactly what happened.

That reflects my experience as someone who’s from there. It’s such an identity; people from outside want that identity so badly, to be someone who can make it in Alaska.

And I’m at the bottom because I’m a teenage girl from California, even though I knew a fair amount about dogsledding. There were all these demographic reasons I was alone, and I started dating someone who was not good for me.

You did it for survival.

And that’s something you, Elisabeth, understand viscerally, being from Alaska. But it is not necessarily intuitive to people who haven’t been in a situation like that. Even when that relationship turned violent, it was still an alliance. He had a mean streak and that seemed to get him pretty far.

Sounds like the alpha male type.

Oh, I hate that term….

Why?

I just think it’s this patriarchal fantasy projected onto animals, and then we use it as pseudoscience to justify human behavior. It’s a bullshit excuse for power-hungry bullies. Dogs know better than that, but we don’t.

That geographic isolation—and, in turn, that loneliness—is partly why domestic violence in rural Alaska remains such a huge issue.

Yeah, it can feel safer to handle violence from one person than from the world at large.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.