Google is the latest technology company to drop the longstanding wall between anonymous online advertising tracking and user’s names.

By Julia Angwin

(Photo: Scott Barbour/Getty Images)

When Google bought the advertising network DoubleClick in 2007, Google founder Sergey Brin said that privacy would be the company’s “number one priority when we contemplate new kinds of advertising products.”

And, for nearly a decade, Google did, in fact, keep DoubleClick’s massive database of Web-browsing records separate by default from the names and other personally identifiable information Google has collected from Gmail and its other login accounts.

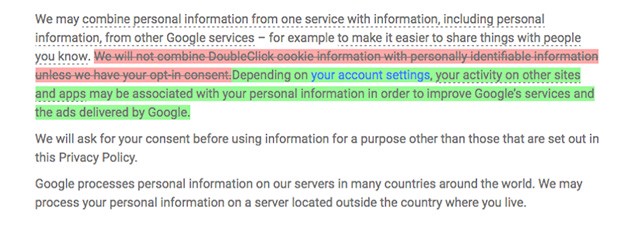

But this summer, Google quietly erased that last privacy line in the sand — literally crossing out the lines in its privacy policy that promised to keep the two pots of data separate by default. In its place, Google substituted new language that says browsing habits “may be” combined with what the company learns from the use Gmail and other tools.

The change is enabled by default for new Google accounts. Existing users were prompted to opt-in to the change this summer.

The practical result of the change is that the DoubleClick advertisements that follow people around on the Web may now be customized to them based on your name and other information Google knows about you. It also means that Google could now, if it wished to, build a complete portrait of a user by name, based on everything they write in email, every website they visit, and the searches they conduct.

The move is a sea change for Google and a further blow to the online ad industry’s longstanding contention that Web tracking is mostly anonymous. In recent years, Facebook, offline data brokers, and others have increasingly sought to combine their troves of Web tracking data with people’s real names. But, until this summer, Google held the line.

“The fact that DoubleClick data wasn’t being regularly connected to personally identifiable information was a really significant last stand,” said Paul Ohm, faculty director of the Center on Privacy and Technology at Georgetown Law.

“It was a border wall between being watched everywhere and maintaining a tiny semblance of privacy,” he said. “That wall has just fallen.”

Google spokeswoman Andrea Faville emailed a statement describing Google’s change in privacy policy as an update to adjust to the “smartphone revolution”

“We updated our ads system, and the associated user controls, to match the way people use Google today: across many different devices,” Faville wrote. She added that the change “is 100% optional—if users do not opt-in to these changes, their Google experience will remain unchanged.”

Existing Google users were prompted to opt-into the new tracking this summer through a request with titles such as “Some new features for your Google account.”

The “new features” received little scrutiny at the time. Wired wrote that it “gives you more granular control over how ads work across devices.” In a personal technology column, the New York Times also described the change as “new controls for the types of advertisements you see around the web.”

Connecting Web browsing habits to personally identifiable information has long been controversial.

Privacy advocates raised a ruckus in 1999 when DoubleClick purchased a data broker that assembled people’s names, addresses, and offline interests. The merger could have allowed DoubleClick to combine its Web browsing information with people’s names. After an investigation by the Federal Trade Commission, DoubleClick sold the broker at a loss.

In response to the controversy, the nascent online advertising industry formed the Network Advertising Initiative in 2000 to establish ethical codes. The industry promised to provide consumers with notice when their data was being collected, and options to opt out.

Most online ad tracking remained essentially anonymous for some time after that. When Google bought DoubleClick in 2007, for instance, the company’s privacy policy stated: “DoubleClick’s ad-serving technology will be targeted based only on the non-personally-identifiable information.”

In 2012, Google changed its privacy policy to allow it to share data about users between different Google services — such as Gmail and search. But it kept data from DoubleClick — whose tracking technology is enabled on half of the top one million websites — separate.

But the era of social networking has ushered in a new wave of identifiable tracking, in which services such as Facebook and Twitter have been able to track logged-in users when they shared an item from another website.

Two years ago, Facebook announced that it would track its users by name across the Internet when they visit websites containing Facebook buttons such as “Share” and “Like” — even when users don’t click on the button. (Here’s how you can opt out of the targeted ads generated by that tracking.)

Offline data brokers also started to merge their mailing lists with online shoppers. “The marriage of online and offline is the ad targeting of the last 10 years on steroids,” said Scott Howe, chief executive of broker firm Acxiom.

To opt-out of Google’s identified tracking, visit the Activity controls on Google’s My Account page, and uncheck the box next to “Include Chrome browsing history and activity from websites and apps that use Google services.” You can also delete past activity from your account.

This story originally appeared on ProPublica as “Google Has Quietly Dropped Ban on Personally Identifiable Web Tracking” and is re-published here under a Creative Commons license.