How jail practices are killing people going through opioid withdrawals.

By Jeremy Galloway

(Photo: Peter Macdiarmid/Getty Images)

The overdose crisis has touched almost every corner of the United States. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, over 47,000 people died from overdoses in 2014, most from opioids like heroin, hydrocodone, OxyContin, morphine, and fentanyl.

These deaths are usually preventable with access to naloxone and education about overdose prevention and harm reduction. Most states have passed naloxone access and 911 medical amnesty laws in recent years. But that’s only the first step, and there are critical gaps in implementing those laws on the ground.

One of the widest gaps is in our corrections system. People are dying from overdoses in significant numbers shortly after they’re released, we know that. But they’re also dying within weeks of being arrested.

There’s a commonly held notion that withdrawal from opioids is a miserable experience, but not fatal. Once, when I was homeless and reached out for help, a treatment hotline told me I didn’t qualify for a bed in a detox program because “heroin withdrawal won’t kill you.” I was in jail within two weeks.

Fortunately it didn’t kill me. But recent incidents at jails across the country demonstrate that opioid withdrawal, and the related symptoms, can be deadly. With proper medical care and access to evidence-based treatment, however, it needn’t be.

Dying for Help

Since 2015 there have been at least four prominent cases of people dying in jails from opioid withdrawal symptoms. Some symptoms, like anxiety, runny nose, muscle aches, or insomnia, can be minor. More severe symptoms include vomiting and profuse diarrhea, leading to dehydration, and, in extreme cases, convulsions, seizures, and delirium. In a closed setting with limited access to medical care, inadequate nutrition, and crowded, unhygienic conditions — as is the case in many county jails — this can yield potentially fatal results.

In March 2015, 18-year-old Victoria “Tori” Herr died in a Pennsylvania jail after being arrested on drug charges. According to several inmates, Tori was denied medical aid. Her mother told local news: “She was basically sentenced to death before she even saw the judge.” Her family started a Facebook group which now has almost 5,000 members.

In June 2015, 32-year-old David Stojcevski, a Detroit man enrolled in a medication-assisted treatment (MAT) program, died while serving a 30-day sentence for careless driving. His family has filed a lawsuit, citing an “excruciatingly painful and slow” death from “acute withdrawal from chronic benzodiazepine, methadone and opiate medications” and the incident is being investigated by the Federal Bureau of Investigations.

In September 2015, 23-year-old Krista Deluca died in a California jail cell from what the Santa Cruz county coroner described as “severe heroin withdrawal symptoms.”

In January of this year, Kellsie Green, 24, died in an Anchorage, Alaska, jail during heroin withdrawal. Her father says: “You go to bed at night and pray that your child will be arrested and taken care of. You hope this will be a second chance, not a death warrant.” The Alaska Correctional Officers Association blamed the situation on jail medical staff — claiming that they refused to treat inmates or disagreed with assessments of corrections officers, and saying she should have been “in a hospital bed, not a prison cell.”

Chronic pain patients are denied opioid medications in most U.S. correctional facilities. And people with substance-use disorders (SUDs) are widely considered to have a health condition, which often requires medical treatment, but are almost universally denied care, which groups like the American Civil Liberties Union consider a violation of the Eighth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

The Federal Bureau of Prisons has detoxification guidelines for withdrawal, which describe a protocol of librium (a mild sedative) and clonidine (a blood pressure medication), with regular checks by medical staff. Most U.S. inmates, though, enter county jails, which aren’t subject to federal guidelines.

One county jail in Florida and jails in Rhode Island, Baltimore City, Seattle, and Philadelphia, provide MAT to inmates, but most jail and prison officials don’t view treatment — including maintaining MAT for patients like Stojcevski — as their responsibility. Yet continuity of treatment and access to medication for people with opioid-use disorders are critical both for post-incarceration success and to give inmates the best chance of staying alive.

Benefits of Continued Treatment During Incarceration

Studies overwhelmingly associate proper medical care and continued access to MAT with positive post-release outcomes.

A 2009 study published in the Journal of Psychoactive Drugs confirmed that opioid-dependent inmates who were denied MAT or other medical care not only suffered unnecessarily, they engaged in “a variety of unhealthy behaviors designed to relieve withdrawal symptoms,” created unhealthy and uncomfortable conditions for fellow inmates, and were less receptive to MAT upon release. The study confirms the need to either provide supervised medical detoxification or MAT for these inmates.

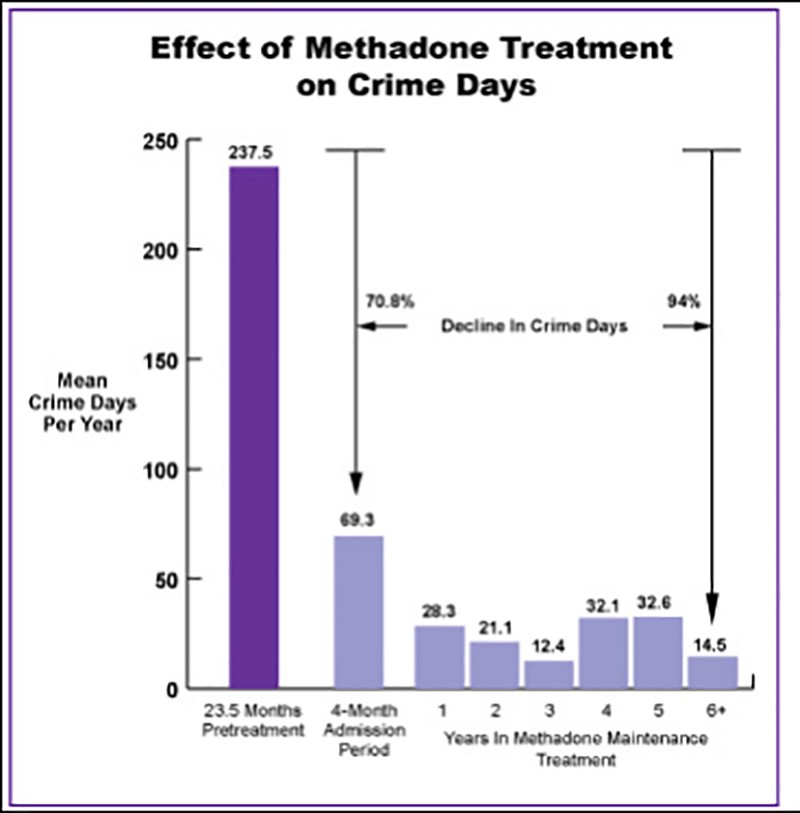

The reduction in crime days for people undergoing long-term methadone maintenance treatment. (Photo: NIDA International Program)

A 2015 study of Rhode Island inmates in MAT programs showed that inmates maintained on methadone during incarceration were “more than twice as likely than forced-withdrawal participants to return to a community methadone clinic within one month of release.”

A long-term (1985–2012) Australian cohort study published in 2014, with over 16,000 subjects, followed inmates with a history of MAT as they entered and left prison. The study revealed that the “lowest post-mortality was among those continuously retained on [MAT].” It also showed the highest risk of death occurred in the group that received no MAT. The study’s data models showed a 75 percent reduced risk of death after exposure to MAT programs within the first four weeks of release.

Data from the same study showed that, in the first four weeks of incarceration, those maintained on medication were 94 percent less likely to die from all causes, while long-term results showed the same population was 75 percent less likely to die over a longer period, resulting in an overall 87 percent lower likelihood of death for medicated inmates.

Numerous other studies (here, here, here, and here) associate MAT with reductions in mortality, illicit substance use, property crime, recidivism, and health problems like HIV and hepatitis C.

Releasing Inmates With No Safety Net

Many people with SUDs already face obstacles navigating daily life, like maintaining a job, stable housing, education, and vital relationships with family and friends. Formerly incarcerated people face all of these obstacles upon release, and others, too.

A condition know as Post Incarceration Syndrome (PICS) is associated with many people released from jail or prison. Researchers have suggested this condition be included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders as a subtype of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

A 2013 study published in the International Journal of Law and Psychiatry showed that, in addition to PTSD, formerly incarcerated people exhibited “institutionalized personality traits resulting from incarceration; social-sensory deprivation syndrome and temporal and social alienation.” Added to external difficulties, such as finding steady employment and housing, and restoring relationships, PICS can create a perfect storm of harmful conditions, which might contribute to relapse. Terence Gorksi, a pioneer in addiction studies, specifically indicates “reactive substance-use disorders” as an element of PICS.

Jails and prisons fail to maintain inmates who enter the system on MAT, deny them opportunities to obtain MAT during incarceration, and release them without the resources they need to survive and recover. Naloxone is a lifesaving rescue medication that can reverse overdoses from heroin and other opioids, but nearly every jail or rehab sends at-risk people home without it.

Encouragingly, New York established a pilot program in 2014 to train inmates to use naloxone and, upon completion, leave with a naloxone rescue kit. In 2015 , the Durham County Detention Facility became the first jail in the Southeast (a region with one of the nation’s highest overdose death rates) to provide naloxone to released inmates.

But these are exceptions. Even in areas where third parties equip jails with naloxone for released inmates, it often goes unused.

Missed Opportunities

Correctional institutions, which ostensibly exist to protect us, serve as a key contact point for at-risk populations. When they fail to equip inmates with survival tools, educate them about harm reduction and overdose prevention, or provide critical re-entry services, they’re complicit in the cycle of recidivism, continued suffering from substance use and PICS, and the wave of drug-related deaths in the U.S.

Jails and prisons have a unique opportunity to serve people in need of treatment and divert them from harmful behaviors. But right now, almost every step they take reinforces an incarcerated person’s reasons for using substances.

A drug-related jail or prison term shouldn’t carry a death risk. And rather existing merely to punish, the corrections system should provide incarcerated people with the tools they need to re-integrate into society and live healthy, productive lives.

This story originally appeared in The Influence, a Pacific Standard partner site that covers the spectrum of human relationships with drugs. Follow The Influence on Facebook and on Twitter.