The storm is Florida’s first hurricane in nearly 11 years, and forecasts are looking dire for the Northeast too.

By Eric Holthaus

Hurricane Hermine gathering strength in the Gulf of Mexico just west of Florida on September 1, 2016. (Photo: NOAA/Getty Images)

After a long journey across the Atlantic that began as a swirl of clouds off West Africa on August 17th, Hurricane Hermine is now just hours away from a historic landfall in Florida.

Over the past 24 hours, Hurricane Hermine has rapidly intensified and, as of midday Thursday, has officially reached hurricane status, including sustained winds of greater than 74 miles per hour. Florida Governor Rick Scott has declared a state of emergency, and several local communities in Hermine’s path have begun mandatory evacuations.

Hurricane Hermine is expected to hit Florida later tonight or early Friday — the first hurricane landfall there in a record-setting 3,965 days, a period that has coincided with massive statewide population growth and an increase in coastal vulnerability. As Andrew Freedman wrote today in Mashable, “Florida’s luck has run out.”

The highest resolution weather model we have: 3km HRRR over the next 18hrs:#Hermine pic.twitter.com/yT08bU6KzD

— Eric Holthaus (@EricHolthaus) September 1, 2016

What’s more important than Hermine’s title, though, is the wide range of expected impacts that are now imminent for a stretch of Florida coastline that is especially vulnerable. Hurricane-hunter aircraft from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the Air Force Reserve have been tracking the storm continuously for days, and over the last several hours have documented a broadening of the storm’s size and a notable increase in the storm’s organization — clues that the storm will continue to strengthen until landfall. Hermine is now a fairly large hurricane, which means it packs a heftier punch than a typical Category 1 storm.

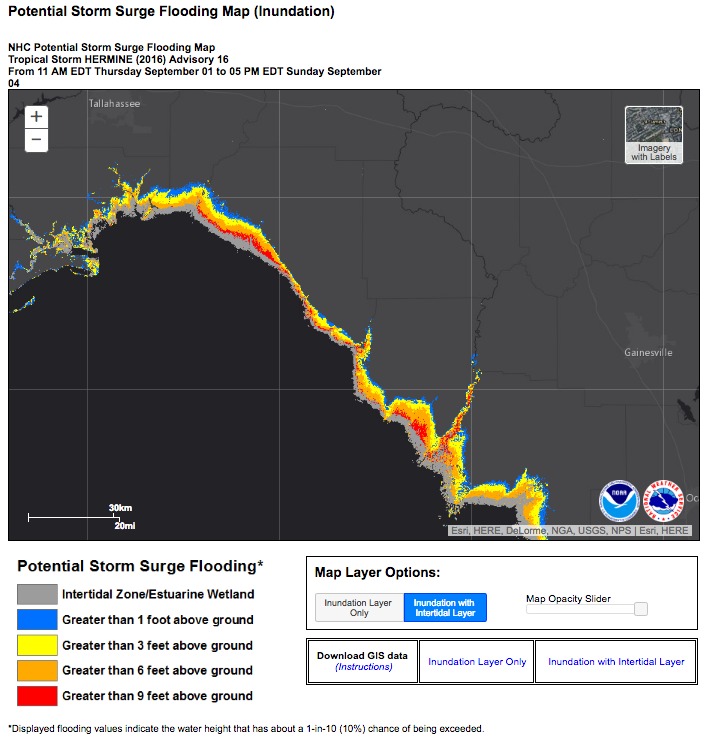

During the day on Thursday, the National Hurricane Center expanded its suite of coastal warnings and watches further south to include the Tampa Bay area, noting that a “life-threatening” storm surge is predicted within the next 12 to 24 hours between roughly Apalachicola, in the Panhandle, to Tampa, the second-largest metro area in the state with a population of more than four million. The highest risk of coastal flooding lies in the area between Alligator Point, south of Tallahassee, to Keaton Beach, in the Big Bend region, where the combination of the concave shape of the coastline and a very shallow-sloping offshore shelf may enhance the hurricane’s flooding impact.

Even though we think of Florida as hurricane-prone, most people who live there are probably out of practice when it comes to preparing for a disaster like this.

In a worst-case scenario, estimated at a 10 percent chance of high tide matching up with peak hurricane-related surge, Hermine could push water levels to more than nine feet above ground in this region — enough to wash away coastal homes when combined with powerful 15-foot waves. By some estimates, this is among the most vulnerable sections of coastline in the United States to storm surges.

(Image: National Weather Service)

In addition to potentially severe coastal flooding, the entire region of northwest Florida is expected to get five to 10 inches of rain in the next 24 hours, with isolated areas receiving as much as 20 inches. That intensity, at the top end, is roughly on par with the peak day of the catastrophic rains that plagued Louisiana last month.

Florida’s current hurricane-free streak is nearly 1,800 days longer than the previous record-long Florida hurricane drought, and, historically, hurricanes have hit the state once every year or two, not once a decade. For the specific stretch of Florida coastline that Hermine is targeting, it’s been even longer: Since 1950, there have been only four hurricanes to pass within 50 miles of Tallahassee, the booming state capital, and the last (Earl, in 1998) was nearly 20 years ago. Since then, the Tallahassee metro area has grown from about 300,000 to about 375,000, an increase of 25 percent. The Tampa Bay metro has added about a million people in the same time frame.

This is all to say that, even though we think of Florida as hurricane-prone, most people who live there are probably out of practice when it comes to preparing for a disaster like this.

Latest (12Z) Euro still has #Hermine at or near hurricane status for 5 days off NJ/NYC/Long Island next week. pic.twitter.com/vAYSwf2evX

— Eric Holthaus (@EricHolthaus) September 1, 2016

And the latest weather models show that Hermine won’t fizzle once it hits Florida. The National Weather Service predicts very heavy rains along Hermine’s anticipated path through southern Georgia and the Carolinas. At that point, things start to get even more interesting: Hermine could transition into an even larger and more powerful ocean storm that could plague the Northeast for most of next week.

If you live in New Jersey, New York City, or Long Island, you’ll want to watch Hermine especially closely. The latest forecasts show Hermine stalling off the New Jersey shore, and bringing a potentially major storm surge ashore for up to five days in a row, starting on Sunday. If that scenario begins to look even more likely by Friday, Hermine will be a big deal for folks in the Northeast, very quickly.

(Image: National Weather Service)

As with every weather event in the current era, Hermine also has a climate change connection. Sea levels in northwest Florida have risen by about a foot in the last 50 to 100 years, thanks mostly to global warming — and that rise will add to Hermine’s flooding potential. The Southeast U.S., as a whole, has seen a 27 percent increase in the amount of rain during the most intense weather events over the past 60 years, as warmer temperatures are able to hold more water vapor. Meanwhile, even if experts are calling it “luck” that Florida went more than a decade without hurricane landfall, that aberration itself fits the profile of climate change: In general, climate scientists who focus on hurricanes expect slightly fewer storms, but warn that the ones that do form will be more powerful.