In her new book, Autumn Whitefield-Madrano argues that we’d be better off with a more inclusive way of discussing — and experiencing — beauty.

By Jennifer R. Bernstein

(Photo: Michelangelo Carrieri/Flickr)

If writing about music is like dancing about architecture, then what is the function of writing about beauty? Does beauty not exist to be observed, celebrated, memorialized?

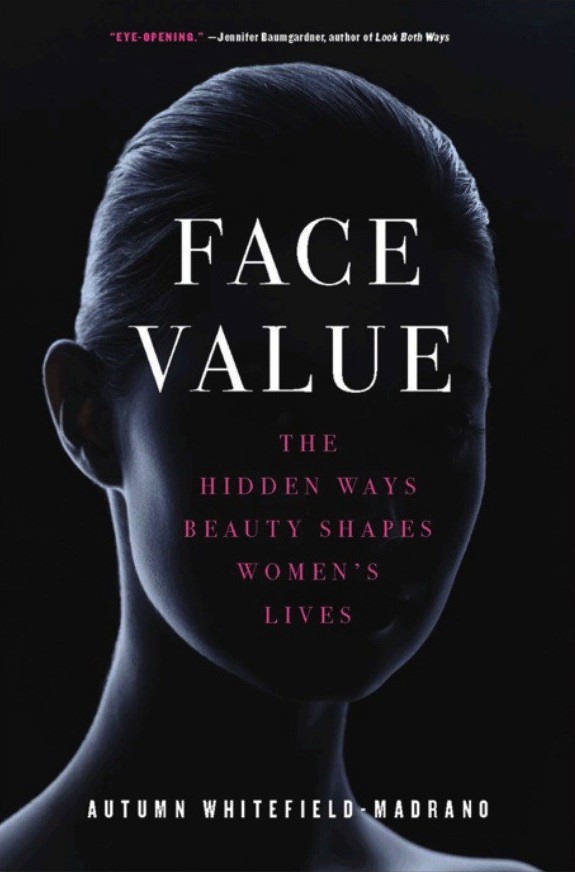

The answer, argued persuasively by Autumn Whitefield-Madrano in her new book, Face Value: The Hidden Ways Beauty Shapes Women’s Lives, is both simple and paradoxical: We talk about beauty too much, and we don’t talk about it enough.

More specifically, Whitefield-Madrano argues that, when we talk about beauty in the modern era, we tend to do so in largely reductive, unhelpful ways. From ancient civilizations to the present, we’ve found ourselves obsessed by beauty, in thrall to its power and to those who wield it. Beauty colors our relationships with one another and with ourselves in ways we have only begun to explore — and so we have an imperative to talk about it, to tell stories about beauty that reflect our experiences and that undermine wrong-headed conventional wisdom. But it is also true that we often scapegoat beauty in order to avoid touching upon deeper matters. We say, “I feel unattractive today,” when really we mean, “I’m worried about how work will go today” — or “You look lovely” when we mean, “I am drawn to your kindness.” In our appearance-obsessed world, it’s no surprise that beauty talk has become a universal stand-in for discussions of what ails us, and what brings us joy.

Whitefield-Madrano has spent the past decade writing about beauty with nuance, humor, and erudition, on her long-running blog The Beheld, and in Salon, Jezebel, the Guardian, and elsewhere. If contradiction lives at the heart of beauty, then Whitefield-Madrano, a lifelong reader of teenage beauty magazines who also has a solid grounding in second-wave feminism, is well poised to untangle its knots.She weaves together practical wisdom and academic theory in order to help readers — particularly, though not exclusively, women — navigate the ins and outs of contemporary beauty culture, which has grown exponentially in breadth and complexity even within the last decade.

Whitefield-Madrano casts a skeptical gaze on all totalizing ideologies of beauty, avoiding prescription and condemnation, instead paying close attention to the particulars of women’s experiences across race, sexuality, and gender expression.

Face Value, a themed meditation on beauty in contemporary life, delivers on the promise of Whitefield-Madrano’s previous work. It is smart, even-handed, and personal, the last of which I mean as pure praise: The author makes no bones about having lived her life wrapped up in the theory and practice of beauty culture, often drawing on anecdotes and conversations to illustrate her ideas. We realize, as we read, that for Whitefield-Madrano to refrain from implicating herself would do a disservice to her subject; for beauty is personal, and we should not try to deceive each other that when we talk about it, we are not also talking about ourselves.

Beauty is a bit of a discursive minefield—like sex or class—and demands a sensitive, agile approach to do it justice, especially as beauty culture is still largely the purview of women, who have already endured so much at the hands of the beauty industry, media, and a certain strain of separatist feminism that excommunicates women who shave their legs and wear make-up (good feminists, this line of thinking goes, should shun these burdens of patriarchy-enforced femininity). Whitefield-Madrano casts a skeptical gaze on all totalizing ideologies of beauty, avoiding prescription and condemnation, instead paying close attention to the particulars of women’s experiences across race, sexuality, and gender expression.

Beauty is a teeming nest of contradictions. It is both compulsory — we must engage in a measure of personal beauty work in order to observe social norms — and expressive, a form of play that makes visible our notions of who we are or could be, allowing us to try on and cast off identities as easily as the swipe of a smudge brush. It is both objective — we generally agree on, for instance, who is the most beautiful person in the room, or on the idea that symmetry is important to beauty — and subjective, widely variable based on relationship with the beauty object, perceptions of “inner beauty,” as well as culturally defined beauty ideals, specific to region, era, and class. Whitefield-Madrano seeks not to resolve these contradictions — which are, for the most part, insoluble — but to inhabit them, as a means of perpetual re-negotiation with beauty culture. She frames our relationship with beauty not as “something we must overcome,” but rather as “a powerful portal to a stronger relationship with the world,” a bundle of threads that can lead us toward a better understanding of how we relate to ourselves and each other. If we learn to live with the tensions intrinsic to a beauty-soaked womanhood, then we can let go of guilt and shame around our own desire to feel and be seen as beautiful, and re-purpose the vast reserves of energy presently devoted to these emotions toward more productive, nourishing uses of our time.

Face Value: The Hidden Ways Beauty Shapes Women’s Lives. (Photo: Simon & Schuster)

The book reaches its peaks when it approaches surprising, even heretical conclusions on a subject. The chapter “The Prettiest Girl in the Room” explores the manifold ways beauty mediates relationships between women: how, for instance, the insider-language of beauty can bond us together (like when we implicitly know the difference between foundation and concealer), but also aid in policing of each other’s bodies (like when we snicker at someone’s “cankles”). By teasing out the ways that beauty language encodes social relations, Whitefield-Madrano heightens our consciousness of how judgments about appearance shape every one of our interactions.

But here, as elsewhere, beauty also always points beyond itself. Whitefield-Madrano probes the root causes of beauty-centered friction between women, and finds that appearances can be deceiving. In the case of beauty envy, for instance, she suggests that, when we envy someone’s looks, it isn’t primarily her beauty we covet. Her appearance functions as a surrogate for what we’re really after: her charisma, or intellect, or confidence. And these feelings of longing for some facet of another woman usually contain tendrils of longing for, well, her. “Jealousy,” Whitefield-Madrano writes, “will be little more than fleeting unless it’s paired with fascination — and where there’s fascination, more often than not, there’s something resembling affection.” When we zoom in on ostensibly negative emotions like jealousy and competitiveness, we often find grains of affinity and desire, which point the way to a collective, rather than divisive, beauty culture. If we are honest with ourselves about why we envy other women, we find that the reasons have more to do with our similarities, our shared struggles and goals, than our differences. After all, we tend to envy those who most resemble us, because they offer a realistic vision of who we could be if we were just a little taller, a little sexier, a little smarter. Acknowledging the element of admiration in jealousy may help us let go of the animus.

Whitefield-Madrano does not shy from such observations, even when they challenge powerful ideological currents: The revelation that we can look at a beautiful woman and feel something other than resentment and self-hatred still rocks feminist boats, even a quarter-century after the publication of The Beauty Myth, Naomi Wolf’s book on the physical and psychological harm women suffer under the influence of ubiquitous, unattainable beauty ideals. These ideals, espoused by the fashion and beauty industries, have established an “iron maiden,” a standard of perfection that punishes women who fail to achieve it — which is all of us.

The Beauty Myth became an instant classic because women recognized the truths in its portrait of a punitive, appearance-obsessed society. But it was never the whole truth. In 1991, iconoclastic intellectual Camille Paglia gave a speech at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where she famously said: “We should not have to apologize for reveling in beauty. Beauty is an eternal human value. It was not a trick invented by nasty men in a room someplace on Madison Avenue.” Paglia argued that feminism, like any liberal political ideology, cannot account for visual pleasure because beauty — by its nature anarchic, irrational, wild — defies liberalism’s quaint Enlightenment faith in reason and good behavior. But this species of pleasure exists nonetheless. When confronted with a beautiful woman, Paglia says, she does not feel despondence at her own ordinary looks, but delight in a specimen touching the heights of human loveliness.

A woman’s appearance can function as a surrogate for what we’re really after: her charisma, or intellect, or confidence.

Whitefield-Madrano proposes a sort of synthesis of the Wolf-Paglia dialectic, with an eye toward advancing beauty talk beyond its either-or terms. Yes, she agrees, beauty culture restricts women’s self-presentations, encroaches upon their daily thoughts, and taxes their wallets (her emphasis on the literal cost of beauty provides a refreshingly materialist alternative to narratives around oppression and empowerment). But are women losing it quite as badly as Wolf would have us believe? No, Whitefield-Madrano ultimately concludes. Beauty media, ever savvy to trends among their consumer base, have incorporated the feminist critique of the image into their own advertising strategy. Think of the Dove “Real Beauty” campaign, which featured white-undied women of a broader range of shapes and colors than one usually sees in beauty ads — though still no larger than, say, a size 14, and therefore firmly within norms of gender presentation. Marketing like Dove’s seems, on the surface, to represent an unequivocal improvement over one-note magazine covers boasting slim, airbrushed, white women. Who wouldn’t be relieved at the implication that her body, perhaps a bit fuller in places than she’d like, can represent its own beauty ideal, crow’s feet and all?

But in sussing out the salutary or harmful effects of these campaigns, Whitefield-Madrano goes deeper than just representation; she also considers evidence from behavioral science. Researchers, she writes, have studied the effect of beauty media on women — in particular, the kind of rhetoric that feeds women a story about their appearance-related insecurities in order either to sell a product, or to educate women on the perils of low self-esteem. It turns out that merely drawing attention to how unhappy we supposedly are about our looks … makes us more unhappy about our looks. At baseline, most women consider themselves average-looking. But when they are made to feel ashamed that they don’t find themselves stunning, their self-image tends to plummet. As Whitefield-Madrano puts it, “Thinking of your looks as average does not constitute a self-esteem crisis. What might generate a self-esteem crisis? Thinking of yourself as average when you’re getting the message that it’s sort of pathetic that you don’t think of yourself as beautiful.” (Emphasis original.) Research suggests, in fact, that, in order to protect ourselves from this negative influence, we might be better off not consuming any media that focuses on beauty, regardless of its message. Here our author offers us a third option that typifies her refusal of dichotomies: we need neither stage a rebellion against beauty media, nor swallow it wholesale. We can, in an act of self-preservation, wash our hands of it entirely.

The complexities of the Dove campaign speak poignantly to the difficulties, both personal and political, of navigating the beauty system in which we are all conscripted to labor. In trying to resist this system’s corrosive effects on women’s inner and outer lives, do we work within existing structures and institutions, carving out nooks of joy and play, or do we abandon them entirely for something better? What would that something look like? Could we ever arrive at a world beyond beauty? Should we want to? Like any good book of criticism, Face Value pokes at these questions, while granting the reader generous space to answer them herself, in whatever ways and at whatever pace make sense for her. It offers only a parting of the veil, an opening of possibility for further experiment and exploration, while assuring women that our experiences around beauty are important and valid. This is a brand of beauty feminism to rally behind.

||