What could we possibly learn about the mechanics of elections this year?

By Seth Masket

Hillary Clinton speaks during a campaign event at Ernst Community Cultural Center at Northern Virginia Community College on July 14, 2016. (Photo: Alex Wong/Getty Images)

A presidential election offers something special for political scientists and other election observers: a whole new data point. Those data points help paint a picture of the mechanics of elections, and there are interesting stories behind each one. But this year’s is likely to be less than worthless.

Of course, election observers have plenty of data to work with already. Researchers have detailed records of literally thousands of national and regional elections in the United States and around the world. But for American political observers, presidential elections take on a special significance, and we just don’t have that many to work with. By rough consensus, we’ve decided that the relevant presidential elections for understanding modern election dynamics are those that have occurred since World War II, given the rise of mass media, the president’s role in managing the economy, and our detailed public opinion records since that time. That’s only 17 data points.

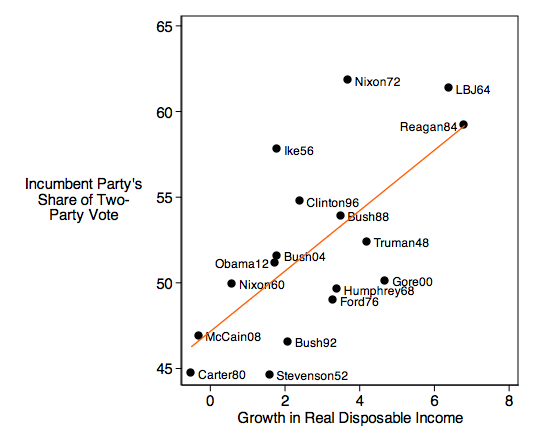

Those few data points can still tell us an important story. Below, for example, is a pretty standard depiction of the relationship between economic growth in the year before an election and the vote for the incumbent presidential party. (The points are labeled for the nominee of the party currently in control of the White House.)

Yes, there are points above and below the trend line, but the trend is still pretty obvious: voters reward the president’s party when the economy is doing well, and they punish it when the economy is doing poorly. This finding is consistent with those of many electoral studies from around the globe, and it’s actually quite comforting. Despite all the noise in presidential campaigns, all the competing media voices, all the spending by campaigns to pull voters away from their preferences, voters overall make their decisions based on something important — the economy — and they hold politicians accountable for its performance. Presidents are incentivized to do what they can to help businesses grow and help people find jobs.

And the individual data points are valuable as well. The fact that Hubert Humphrey and Adlai Stevenson underperformed the economy in 1968 and 1952, respectively, suggests that voters don’t like our involvement in long and bloody wars like those in Vietnam and Korea. Richard Nixon’s over-performance in 1972 gives us a hint that voters like moderates and turn away from perceived extremists like George McGovern.

But, for the most part, all these models make the assumption that both major parties are doing roughly the same thing and are pretty well matched. They’re raising and spending similar amounts of money, they’ve nominated competent candidates who can reasonably articulate party goals while appealing to non-partisans, they’re similarly skilled in identifying undecided voters and marketing to them, etc.

This does not describe 2016.

The rollout of Republican vice presidential nominee Mike Pence, including stories that Donald Trump tried to get out of naming Pence at the last minute, was merely the latest piece of evidence that the Trump campaign is one of the worst run presidential campaigns in modern political history. This is not to suggest it’s easy to run a presidential campaign; it’s fantastically difficult. But leaders in both parties have developed expertise in doing this, and the Trump team has either failed to recruit veteran Republican operatives or has ignored their counsel.

The Trump campaign is one of the worst run presidential campaigns in modern political history.

Relatedly, the Trump campaign has raised staggeringly little money thus far for a presidential campaign. It’s possible they can overcome this shortfall, and it’s also possible it doesn’t matter — many people seem to think they’ve seen Trump advertisements even when they haven’t, and Trump has an uncanny ability to get on television without paying for it. But at least in terms the campaign’s ability to raise money and spend it on communications, the Trump team is just not remotely in Hillary Clinton’s league.

And, finally, there’s the matter of candidate behavior. Trump has seemingly gone out of his way to alienate large swathes of voters, something presidential candidates are typically skilled in avoiding. He is by far the most despised major party presidential nominee in the history of polling.

All of these things are contributing to the fact that Clinton is beating Trump in the polls, despite a number of scholarly estimates suggesting that Republicans should have a modest advantage this year.

So let’s say that the election ends up following current polling, and Clinton wins by five points. Let’s further say that, were the candidates evenly matched, Clinton would have lost by one. So why would she over-perform by six points? In some ways, it would be great for scholars to have an election in which one team campaigned as usual but the other simply chose not to — it would give us some idea as to how much campaign activities actually matter. But would Clinton’s over-performance mean that the campaign mattered that much? Would it mean that campaigns don’t actually matter that much, but insulting women, Mexicans, and Muslims has large negative consequences on the vote? Would it mean that the Republican Party has become too ideologically extreme in recent years, or that Trump didn’t adhere enough to those extreme stances? Or maybe it’s just rank incompetence that’s at fault, with Trump spending resources on states that aren’t really in play?

Campaigns are inherently multivariate affairs, with lots of different influences going on at the same time. And some outcomes will simply have some random aspect to them. But this year’s election seems particularly confounding. A Trump loss would be over-determined. There won’t be, or shouldn’t be, any pundit in mid-November beginning a sentence with “Trump would have won if he’d just….” His loss would have hundreds of causes, and researchers would sadly learn little from it.

||