Behind the Bernie Sanders-inspired expansion of Hillary Clinton’s health-care platform.

By Dwyer Gunn

(Photo: Justin Saglio/AFP/Getty Images)

On Saturday, Hillary Clinton announced an expansion of her health-care platform, as part of a deal to finally secure Bernie Sanders’ endorsement this week. While she stopped short of embracing the single-payer system that Sanders championed throughout his campaign, Clinton reiterated her support for the “public option,” saying she’d allow Americans 55 and older to buy into Medicare. Clinton also vowed to double funding for community health centers, which serve low-income patients in under-served areas.

Technically, Clinton’s support for these ideas isn’t actually new. She’s discussed Medicare buy-in before and is a long-time supporter of community health centers. Clinton supported the inclusion of the “public option,” a government-run health insurance plan that would compete with private insurers and offer an alternative to Americans without employer-provided health insurance, in an early draft of the Affordable Care Act (it was cut from the final legislation in the face of opposition from both Republicans and Joe Lieberman). She included it in her health-care platform back in February, as a more politically feasible alternative to Sanders’ single-payer plan. Taken as a whole, Clinton’s platform is an obvious nod to both the importance of the health-care issue to Democratic voters and to the need for continued reform, especially in the face of the ongoing coverage gap and rising premiums.

Clinton’s re-voiced support for the public option is also particularly salient in light of concerns about competition in health-care exchanges as some large insurers pull out. In fact, on Monday, the Journal of the American Medical Association published an article written by President Barack Obama (which marks the first time the journal has published an article by a sitting president) on the ACA, in which he also called for a public option.

“Now, based on experience with the ACA, I think Congress should revisit a public plan to compete alongside private insurers in areas of the country where competition is limited,” Obama wrote. “Adding a public plan in such areas would strengthen the Marketplace approach, giving consumers more affordable options while also creating savings for the federal government.”

A true health-care revolution will require Americans to confront our conviction that more health care is better health care.

As Obama notes, the public option would benefit markets with limited competition, but economists actually disagree about its effects on overall health-care spending and health-care costs. Back in 2009, public option advocates argued that a large government-run insurance plan would help keep costs down (much as Medicare does today), and the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office estimated that a government-run insurer would have lower administrative costs and charge lower premiums—and, perhaps most importantly, would reduce the federal budget deficit.

Other economists point out that government-run insurers actually haven’t done a very good job of reducing unnecessary medical procedures and expenditures (one of the main drivers of runaway health-care spending) and contend that the public option would drive private insurers out of business and ultimately reduce the supply of medical providers. In other words, a public option solves some of the health-care challenges we’re currently facing, but a true health-care revolution will require Americans to confront our conviction that more health care is better health care.

Interestingly, Clinton’s proposal to essentially double federal funding for community health centers (to $40 billion over the next years) might actually be the first step in a true health-care revolution. Community health centers, of which Sanders is a passionate advocate, are universally acknowledged to provide excellent care to highly vulnerable populations, in an extremely cost-efficient manner. A brief published last year by the Kaiser Family Foundation laid out the benefits of community health centers. For starters, they serve exactly the kinds of patients that other providers often turn away (they don’t refuse care to anyone) or struggle to connect with.

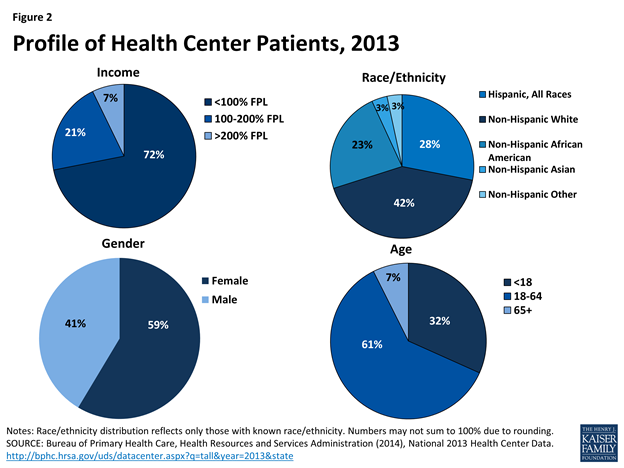

(Charts: Kaiser Family Foundation)

The chart at left illustrates the demographics of community health center patients.

Last year, according to Dan Hawkins of the National Association of Community Health Centers, 1,400 community health center organizations provided care to 22 million people at nearly 10,000 sites in all 50 states. And that care goes beyond check-ups and vaccines —community health centers provide patients with a range of wrap-around services, including nutrition counseling, housing assistance, skills training, free legal aid, transportation assistance, translation services, and outreach.

Numerous studies have confirmed that community health centers provide excellent care. They reduce infant mortality rates, reduce mortality rates for older Americans, reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health outcomes, and more successfully deliver preventative care to high-risk patient populations than non-community health center providers. Their ability to erase deeply entrenched racial health disparities is particularly impressive.

In a paper published in 2001 in the International Journal of Health Services, the researchers found that “while racial/ethnic disparities in health persist nationally, these disparities do not exist within community health centers, safety-net providers with an explicit mission to serve vulnerable populations.” And they provide that care at a discount to any other type of provider (private physicians, hospitals, etc.). The Clinton campaign’s briefing estimates that community health centers save the health-care system over $49 billion each year.

They’re also administered in a truly revolutionary way. “The most important feature that differentiates health centers from pretty much every other provider of care is that each and every health center has a board of directors, a policy board, a majority of whose members must be active, registered patients of the health centers,” Hawkins says. “It ensures the centers are responsive to the needs of the people and the community they serve. When they find out there’s a problem, they will look for a partner and a way to solve it.”

Peter Shin, a professor at George Washington University and the lead author of last year’s Kaiser brief, points out that an investment in community health centers also doubles as an investment in economically distressed communities. The centers often serve as a crucial employer and economic force in the economically distressed communities they serve. The Department of Health and Human Services reports that health centers employed 157,000 full-time workers in poor communities in 2013, and the NACHC estimates that health centers create an additional 112,000 local jobs.

“Bringing $40 billion into these communities is something that politicians should really brag about,” Shin says. “Health centers tend to anchor the community, both in terms of the economy and health services.”

||