In April of 2014, on a flat, dry stretch of western Kenya, Loice Ocholla described to me the ways that foreign non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have tried but failed to change her impoverished homeland. She recalled one project that distributed livestock in her neighborhood for families to raise and sell. “They give just one goat, and if it dies that is not their concern,” says Ocholla, a 26-year-old teacher and mother of two. She says that NGO has long since disappeared. Ocholla’s neighbor, Caroline Ogutu, a mother of five who farms maize and millet, likened the top-down aid projects she has seen here as “someone telling you, ‘You must buy a table’ — but you already have a table, and you don’t need a table.”

A few years back, one NGO decided to do things differently. It began by handing out cash transfers of approximately $1,000 — close to Kenya’s average annual income of $966 right before the program launched in 2011 — to each family, with no strings attached. The handouts were no wild attempt at foreign philanthropy. Rather, they were the calculated byproduct of a scientific experiment that found unconditional cash transfers to be incredibly effective at improving the livelihoods of families living in western Kenya’s Siaya County.

Farmers I met who had received the cash showed me new tin roofs over their homes, pigs they were raising, electrical inverters they use to charge up neighbors’ phones for a fee — all purchased with cash from GiveDirectly. But unlike many aid interventions, the evidence that this worked is not merely anecdotal; not just some photograph of a smiling family on the charity’s website. Rather, it comes from a rigorous study of the program, which compared nearly 500 of the families that received cash to nearly 500 that did not. The study found that those receiving cash saw their assets increase 58 percent over the course of a year. By comparing families that had received the cash to families that had not, the study was able to prove that recipients fared far better than non-recipients, and that the handouts themselves — not chance — are what spurred their improvement.

The idea that simply handing out cash could effectively alleviate poverty once seemed ludicrous—until scientists began proving that it works.

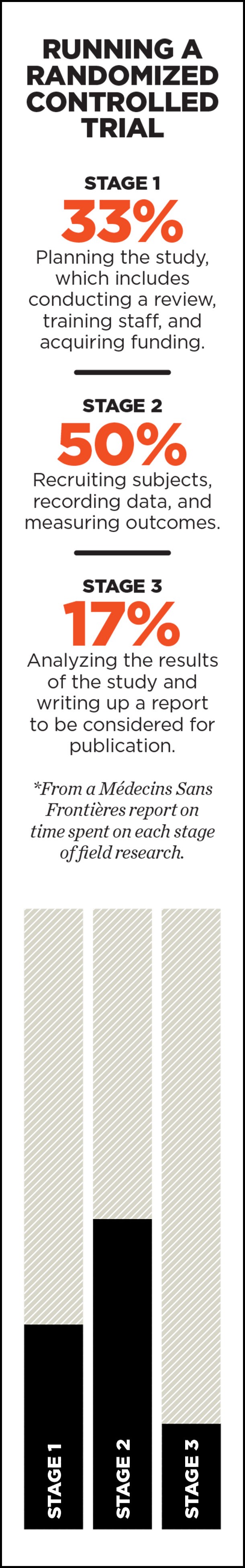

Called a randomized controlled trial (RCT), this type of study is little more than a real-world manifestation of a school science project. Students learn how to test a hypothesis using a control group; drug corporations use the same methods to test new pharmaceuticals, as do advertising agencies looking to evaluate the effectiveness of a television spot.

As the name implies, RCTs use a control group that allows researchers to answer a question so rarely asked in the aid industry: Yes, this intervention seems to have worked — but might people’s situations have improved even without it? In science, it’s what’s known as the counterfactual.

Then there’s the randomness factor. In an RCT, people suffering from poverty, poor health, or other ailments are randomly assigned to the control group or one of the treatment groups. The randomness solves the problem of individual choice — what if those who chose to participate in a given aid intervention were already the go-getters in their community, self-selecting in a way that would taint results?

The RCT has become a sort of gold standard for testing interventions, but only recently has it made serious inroads into development aid, a field known for justifying its existence using anecdotal, often emotionally charged success stories rather than data.

For too long, “accountability” in the aid industry has meant nothing more than ensuring that a donor’s money was spent the way an agency said it would be. Rarely did organizations examine whether their spending achieved a positive impact (improved access to water, for example), much less one that stood the test of time (meaning the well didn’t dry up).

But recently, many aid organizations, including the International Rescue Committee, a New York humanitarian aid group specializing in refugee assistance, have used RCTs to, among other things, evaluate methods for nudging parents in Liberia toward more effective parenting techniques and to create highly effective community savings-and-loan programs to combat poverty in Burundi. It’s easy to see why charities are attracted to RCTs: They can make an aid agency’s work more efficient and generate solid evidence of progress to show funders.

As organizations continue to conduct more of them, RCTs are disproving many myths upon which we’ve designed development aid for years, not least of which is our longtime preference for projects over cash. If the data shows, as the RCT of GiveDirectly’s Kenya program did, that it’s most effective to hand a family $1,000 with no strings attached, then that’s precisely what we should do.

RCTs are no cure-all; rather, they are the best tool we have to identify a whole range of cures that might, collectively, do the trick. RCTs can direct us toward the lowest hanging fruit— and then show us the most efficient way to pluck them from the tree.

Proponents of RCTs, who sometimes refer to themselves as randomistas, believe that the sort of anecdotal appeals that we used to rely on when deciding where to donate our money—the needy, wide-eyed child photographed at an orphanage, or the smiling mother who received access to a water well dug by a foreign charity— simply aren’t enough. If the overarching criticism of development aid is that there is too little actual evidence that it works—well, they say, it’s time for more evidence, of the scientific and quantitative kind.

If the randomistas are correct, the newly scientific approach to aid may usher in a sort of enlightenment—an era of unprecedented accountability that will produce new areas of knowledge that philanthropists can use to accomplish goals they’ve always aspired to. If the randomistas are wrong, it will be because their methods prove expensive and non-transferable.

Critics argue that the findings of an RCT conducted in one place aren’t necessarily applicable in another. If true, this would require replicating RCTs far and wide, which could make them too expensive to be feasible. Others worry a wealth of scientific evidence alone won’t cure the deep ailments of the aid industry. Aid agencies and NGOs, they argue, might prefer to stick with the aid interventions they know rather than adopt the ones they don’t.

There’s also the argument that most philanthropy is motivated by self-serving or irrational means — that donors don’t tend to base their giving on evidence and reason in the first place. Still others object to the ethics of selecting one group of people to receive a treatment while another does not.

Among this last cohort is Paul Farmer, the Harvard Medical School professor who founded Partners in Health, a highly respected NGO built upon Farmer’s ideology that the poor people of the world ought not just have efficient care, but world-class care. Farmer’s ethical gripe with RCTs is this: If we test the efficacy of unproven treatments, that means we’re temporarily giving treatments that we aren’t yet sure work. There are two problems with this logic. First, by following it, we’ll never test new programs and therefore we’ll never learn what actually works. Second, the alternative Farmer is offering is to go ahead treating people in ways that haven’t been vetted by the most rigorous standards — precisely the thing he proclaims to be rallying against.

Randomistas don’t go into people’s homes and steal their mosquito nets at night. They simply offer them to people who don’t yet have them.

A related concern is that a control group will be denied a treatment that’s believed to work, but it’s not the case that RCTs are taking away treatments. Randomistas don’t go into people’s homes and steal their mosquito nets at night. They simply offer them to people who don’t yet have them.

But randomistas face the challenge of buy-in. Identifying a solution to a problem doesn’t guarantee we will succeed at implementing it. For decades, RCTs have proven the effectiveness of vaccinating children against measles, and conclusively disproven the myth that vaccinations cause autism. But that hasn’t stopped some parents from ignoring the science and refusing to vaccinate their children.

Behavioral economists in support of the randomista movement, though, say RCTs may yet overcome this sort of resistance. Many RCTs don’t merely identify ideal treatments, but actually test the best ways to persuade people to participate. Studies have found, for example, that the number of organ donors skyrockets when, instead of asking someone registering for a new driver’s license whether they would like to opt in, you make them a donor by default and give them the option to opt out — an option few people take. But can this sort of nudge theory work as effectively when it comes to more complicated problems, such as the suffering that occurs when an authoritarian government prevents food aid from reaching its political or ethnic minorities, or the reluctance of well-to-do nations to open their doors to more refugees? The randomista movement is unlikely to fix the political environment in which aid operates.

RCTs can, at the very least, help us eliminate aid programs that are wasteful or ineffective; they can guide us in directing our money toward methods proven to work. Take cash transfers, like the GiveDirectly program in Kenya: Columbia University professor Christopher Blattman conducted an RCT on a similar government program in Uganda that found that “the program increases business assets by 57 percent, work hours by 17 percent, and earnings by 38 percent.”

Cash transfers are now being implemented widely, for the benefit of Afghan families and Syrian refugees, and from post-earthquake Haiti to New York City, where one organization gave away $8,700 each to thousands of poor families. In that experiment, “a randomized evaluation showed that self-employment went up and hunger and extreme hardship went down,” in Blattman’s words. There are many proposals to scale cash-transfer programs in humanitarian aid, and some have even advocated using them to provide direct dividends from resource-rich developing-world governments to their citizens (imagine if you earned money on every barrel of oil produced by ExxonMobil).

Cash transfers embody precisely the sort of thing that a data-driven approach to aid can uncover: new, even unthinkable alternatives to helping the poor. The idea that simply handing out cash could effectively alleviate poverty once seemed ludicrous — until scientists began proving that it works.

For too long, aid to the developing world — a multibillion-dollar industry with the intention of transforming the lives of the world’s poorest people — has been exempt from the scientific scrutiny with which we approach far less important tasks. Think of RCTs as a method for identifying the little ideas that, if scaled up, might actually get the job done.