We rely on parents to teach their sons not to rape, but there’s no good reason to believe they know how.

By Malcolm Harris

(Photo: Santiago Arciniegas/Flickr)

I’m sure Brock Turner’s parents thought they were protecting him when they begged Judge Aaron Persky to spare him from the full consequences of his conviction for sexual assault. The letters from his mom and dad may have kept Turner out of jail for more than a few months, but they also have helped make him the poster-boy for coddled rapists everywhere. Between his father Dan, who worried about his son’s vanished ability to enjoy ribeye steaks, and his mother Carleen, who lamented that she no longer had the inspiration to decorate their house, there’s no indication that the Turner family felt any compassion for the woman who was assaulted. It’s clear they bought his pat story about a drunken hook-up gone bad. At least that’s what they’re saying in public.

Given the horrors of the American penal system, it’s hard to blame any parent for trying to keep their child clear of its walls. “Look at him,” Carleen wrote to Judge Persky, “He won’t survive it … Stanford boy, college kid, college athlete—all the publicity…. This would be a death sentence for him.” She’s not wrong to be afraid, even if her prison-movie nightmares have a racist tinge — being an unpublicized teenager didn’t make jail any more survivable for Kalief Browder. Incarceration isn’t redemptive or educational, and a good parent plays every card they have to hold onto their child. But where is the line between support and complicity, between being a good parent and a bad person?

I asked parenting expert Rosalind Wiseman (most famous for her book Queen Bees and Wannabes, which became the movie Mean Girls — her latest book Masterminds and Wingmenis about raising boys) about the Brock Turner case. How far should parents go to protect their sons from the consequences of their hurtful actions?

If you’re an adult, American society and the law itself have changed their minds about generally accepted levels of sexual coercion during your lifetime.

Wiseman sees this question come up most frequently in academic settings, and she’s not sympathetic to parents who try to keep their kids in school after they’ve harmed another student. “These parents fight administrators on expulsion, and the only thing that happens if that kid stays in school is he is empowered to keep doing it,” she says. “You really are in a situation as the parent of deciding: ‘I have a responsibility to raise my child to be a decent human being who does not make other people miserable and is not a threat. That is more important than his attendance at this school.’”

One of the things that’s so appalling about the Turner letters is that it’s obvious the parents would rather have a happy rapist Olympian for a son than direct the moral rehabilitation he so clearly needs. That attitude is a violation of the implicit agreement society has with individual parents not to raise predators.

Parents of a convicted rapist have already failed, insofar as successful parenting involves not raising a rapist. There’s more than enough blame to go around, but parents are considered uniquely responsible for their children’s moral development. They’re supposed to teach their boys not to rape. That might sound obvious, but then the meaning of that duty, and of rape, has shifted over time. When Donald Trump’s lawyer answered a 1989 allegation from Trump’s ex-wife Ivanka with “You can’t rape your spouse,” he was wrong, but only by five years. (By 1984, spousal rape was recognized as illegal in New York.) If you’re an adult, American society and the law itself have changed their minds about generally accepted levels of sexual coercion during your lifetime.

These questions aren’t theoretical for Wiseman; she reminds me that she has two sons, ages 13 and 15. “I’ve heard of a lot more and seen a lot more dads saying that they’re going to talk to their sons about sexual assault,” she says, “and that’s a really important step. I just don’t know what they’re saying.” It’s not enough to have a conversation; it’s the content of the conversation that really matters.

A pamphlet printed by the Department of Education in 1984 called “Where Do I Start? A Parents’ Guide for Talking to Teens About Acquaintance Rape” pointed to generational gaps as a stumbling block: “Sexual assault is a relatively new topic of discussion in our society. We can’t just fall back on what our parents told us.” It’s a noble sentiment, and one of the instructions from the pamphlet that holds up. Not everything in there does.

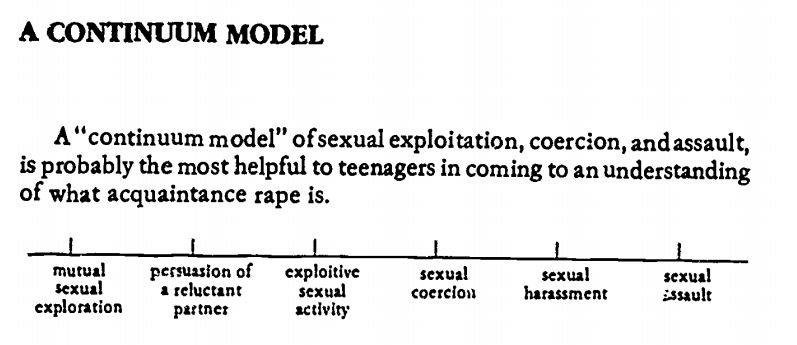

The idea of acquaintance rape or date rape was — as the pamphlet says — relatively new in 1984. To make sense of it, authors Py Bateman and Gayle Stringer suggest a “‘continuum model’ of sexual exploration, coercion, and assault.” They number behavior one to six, from mutual sexual exploration (1) to sexual assault (6). Persuading a reluctant partner (2) is considered copacetic as long as you’re nice about it, while catcalling (5) is worse than coercion without physical violence (4). At the time, the line for unlawful behavior seems to have been somewhere around five and a half. “Exploitative sexual activity” (3) includes boys lying to girls and girls “trading sexual favors for presents or dates.” The pamphlet also begs the question: “How can girls make judgments about possibly vulnerable situations like drinking?” Today, consent educators encourage us to question these kind of assumptions; is there any amount of wine that makes a women’s book club an exceptionally “vulnerable situation”? Drinking isn’t the problem.

(Photo: Where Do I Start?)

There’s a certain danger to telling American men to talk to their sons about rape and assuming they have the knowledge or understanding to do it well. “When we think about men talking to boys,” Wiseman says, “you really do need to challenge the nature and quality of that conversation. If it’s pathologizing women, demonizing women, or using the tropes of manipulation or emotional reactivity, where women don’t know what they want or change their minds the next day, then that reinforces the problem.” The pamphlet from 1984 — which presumably represents some of the most progressive mainstream thinking of the time — traffics in these misogynist stereotypes, with the idea of persuading women into sex framed as normal and probably necessary. Except, that is, when girls are deploying their own set of exploitative tricks, like trading sex for dates.

American fathers born in the 1970s and ’80s, if they even received an explicit talking-to about rape, probably got some variation on the ’84 pamphlet; most likely a significantly worse version, considering the pamphlet was written by experts. Our understanding of the social causes of sexual assault have changed too; we probably wouldn’t encourage teenage boys to persuade unwilling girls into sex in 2016. Dads may well have a lot to learn — and unlearn — about consent themselves.

Leaving it to parents, then, isn’t good enough. We can’t expect every mother and father to have trained themselves on the latest in consent thinking, especially since many of them haven’t had to navigate consent with a new partner in decades. I don’t think schools are a good environment for it either; students associate school with compliance. Teaching students about consent in a place where they have to ask to use the bathroom sends mixed messages. Perhaps it would be better to approach sexual assault as a challenge of community-level education.

Just because parents have reproduced doesn’t mean they know how to teach their kids about sexual assault. Some of them are, unfortunately, clueless. “Many parents lack the self-awareness to recognize how ineffective they sound,” Wiseman says. “If dads are saying stupid shit like, ‘What about your mother, what about your sister, respect women,’ and not taking it further, that’s not going to work.” On the other hand, if individual moms and dads are exceptionally insightful or understanding, there’s no reason why only their children should benefit. It made me wonder: Why not have “the conversation” as a mediated group? Why not at the clique-level? The nuclear family as an institution has a terrible history when it comes to sexual assault; we don’t need to reproduce its problems, and as a society we can’t afford to rely on the households that are emotionally worst equipped.

In the 1990s, when I was a kid, there was a major effort to educate Americans about the environment. It wasn’t just a question of telling parents to talk to their children about recycling; kids were deputized to take action in their homes and in their communities. In her book Doing Their Share to Save the Planet, Donna Lee King tells stories of kids patrolling parental electricity use and organizing neighborhood clean-ups, a phenomenon I remember well. The environmental message proved too simplistic, but it’s an interesting model for involving children in social change, and social change is what we need when it comes to preventing sexual assault. Some parents might not like the idea of a son or daughter who returns an unwanted hug with a lecture on bodily autonomy, but the world would be better off.

||