In her new book, Death in Ten Minutes: The Forgotten Life of Radical Suffragette Kitty Marion, historian Fern Riddell reconstructs the life of militant suffragette and birth-control activist Kitty Marion. The book is an eye-opening account of the women’s suffrage movement in England and America as told through the personal history of this key member, whom Riddell argues the movement has intentionally forgotten. Despite this erasure, Riddell makes the forceful case that Marion’s voice is “critical to our understanding of the suffragettes, violence, sex, and the complex history of birth control in both the United States and the United Kingdom.” For modern readers, Riddell’s exploration of the sanitization of the suffragette story offers important context for the rise of the #MeToo movement and the persistence of sexism in today’s world.

Marion was born in Germany to an abusive father and a mother who died when Marion was young. She moved to England, where she found a happy home as a performer at music halls famous for their liberal sexual culture. Before long, Marion was haunted by an experience with a male talent agent (whom she calls “Mr. Dreck,” or “Mr. Trash”), who attempted to extract sexual concessions in exchange for employment, as was (and has stubbornly remained) the status quo in the industry. Refusing to accept this as the necessary price for advancement, Marion vowed to never marry or place her livelihood under the control of any man. Instead, Marion continued to find performance work without a male agent and joined the Women’s Social and Political Union, a growing organization of women demanding the right to vote, through which Marion began to sell the suffragette newspaper Votes for Women on the streets of London.

A major part of the suffragettes’ strategy, as Riddell details at length, involved a carefully plotted regime of “unwomanly” destructive violence—not to kill people but to prompt terror, so that the English public might fear for its safety until women were awarded the right to vote. Marion herself spearheaded many attacks and was sent to prison several times, where she and other incarcerated suffragettes went on hunger strikes and underwent horrifying force-feeding procedures before being released for ill health. Riddell laments that the mainstream British feminist narrative has filtered out much of the violent elements from suffragette history, and that the British authorities didn’t really take seriously these women’s acts of terror at the time. Even when WSPU members like Marion were making bombs or burning down homes, male commentators diagnosed the suffragettes’ declaration of war as the banal result of a “lack of social excitement,” according to the analysis in one 1913 news article. (Like sexual abuse in the performance industry, the belief that women aren’t capable of the same physical or mental toughness as men has unfortunately stood the test of time. In practice, women were seen as unfit to serve in combat in the U.S. military until 2015, and men still make up nearly 90 percent of law enforcement officers. Male sports also remain significantly more popular than female sports.)

Marion later moved to New York, where she joined Margaret Sanger’s growing organization fighting to make birth control information and contraceptives widely available (the group would later rename itself as Planned Parenthood). Here, Marion was able to fight for her deeply held belief that women’s freedom should encompass sexual freedom. While working in the music halls, Marion had seen many of her friends enjoying healthy, consensual sexual relationships. As a result, and despite her experience with Mr. Dreck, she rejected the common British feminist view that sex could only ever be used as abuse against women. This difference in beliefs placed Kitty at odds with leaders of the suffragette movement, including Christabel Pankhurst, a WSPU founder, who advocated that women avoid sex with men altogether.

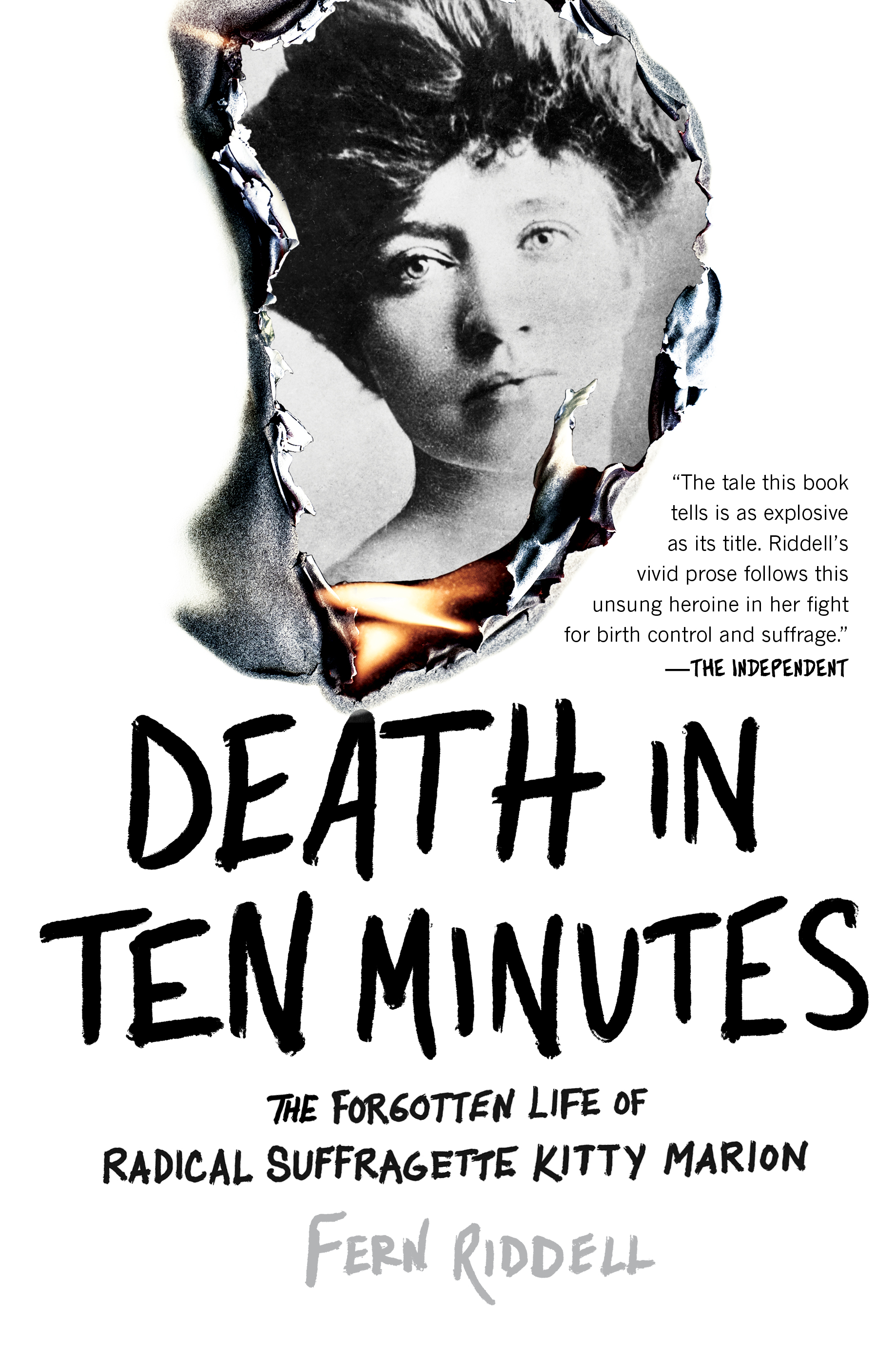

(Photo: Hodder & Stoughton)

By the end of Marion’s life, Riddell writes, a small group of leaders at the WSPU were constructing a vision of how they wanted the “Suffragette Spirit” to be remembered: “[A] noble heroine whose purity and morality were the reason men had come to their senses and awarded women the vote became the idolized cultural memory of the fighters of the WSPU.” This small group of women leaders compiled many of the documents, memoirs, and memorabilia that now sit in the Suffragette Fellowship Collection at the Museum of London, which has served as a basis for much of the current scholarship on women’s suffrage. At the same time, when this revisionist group decided to filter out inconvenient stories about suffragettes’ radical militant tactics and their support for birth control (including omitting Marion’s entire autobiography), they minimized or obscured the true and full account of women’s passionate struggle for equality—and helped to entrench the stereotype that women could or should only ever be docile and passive.

At the end of the book, Riddell discusses the sexual assault allegations against Harvey Weinstein, raised by actresses who had needed to remain in his good favor if they wanted to get work. As Riddell notes, these events illustrate how little has changed over the past century within a larger culture of male sexual manipulation, and especially within show business. The #MeToo movement in the digital age has given women a platform to raise their voices and know they will be heard and validated, and has prompted important conversations about the meaning of consent. While that’s empowering, it also terrifies me to see a seemingly endless string of friends, acquaintances, and strangers come forward to say that they, too, have been sexually assaulted, harassed, or otherwise mistreated. Even the president of the U.S. has been accused of serial sexual misconduct.

As a woman coming of age in this era when people are opening up about sexual abuse more than ever before, it’s tempting to think that I live in a largely progressive society that is listening to survivors and finally punishing (some) perpetrators of traumatic, manipulative attacks against women. On top of that, women in the U.S. have had the right to vote for nearly 100 years, and birth control is now widely accessible. Yet the wage gap persists, and I still hear stories from my female friends about women who make less money than their male colleagues with the exact same qualifications and experience, or who have to field questions at job interviews about how having a baby will one day affect their ability to conduct scientific research, or who have been publicly ridiculed and fired for having a consensual sexual encounter with a male superior.

Winning the right to vote was monumental, but when feminist historians ignore the dramatic lengths women went to in pursuit of their rights, that abridged history supports a traditionalist concept of womanhood that ultimately slows women’s progress toward being treated as equal members of society, even in 2019. Death in Ten Minutes is an insightful and important read because it gives an unrestricted account of how women forcibly demanded their right to vote; it’s especially important in holding accountable certain leaders of the women’s suffrage movement for the damage they did—not just to physical property, but to the ongoing fight for women’s rights.

Pacific Standard’s Ideas section is your destination for idea-driven features, voracious culture coverage, sharp opinion, and enlightening conversation. Help us shape our ongoing coverage by responding to a short reader survey.