For many non-heterosexual people, gay bars help us find our way. They are often the most accessible safe spaces available.

By Lisa Wade

A woman lights a candle during a candlelight vigil for the victims of the Pulse Nightclub shooting in Orlando, Florida, at Oxford St. on June 13, 2016, in Sydney, Australia. (Photo: Daniel Munoz/Getty Images)

Sunday, I woke up to the news “that someone had shot up a gay club in Orlando and there were many injured and killed.” I then went about my morning getting ready to go to a gay family picnic celebration. There would be a jumping castle and lots of games and fun stations set-up for kids to play. The news hadn’t sunk in yet, and I didn’t look for details. There was some talk at the event and a couple folks said they were glad this celebration was taking place at a (and this is my description) “gated” park and that reservations were required to attend. I like to think the reservations were so those organizing the event would know how many to plan for … but now I wonder. Here in New Orleans we still have closed family Facebook groups and operate by rules some of y’all might think are from the days in which social tolerance was much lower.

My initial thought regarding the shooting at Pulse in Orlando was that this was a hate crime planned for Pride. The social psychologist in me guessed some perceived threat had likely led to this event and, indeed, the detail about Omar Mateen’s fury over seeing two men kissing was reported early. It was only after I had returned home that I started to learn the details and that the death toll was rising.

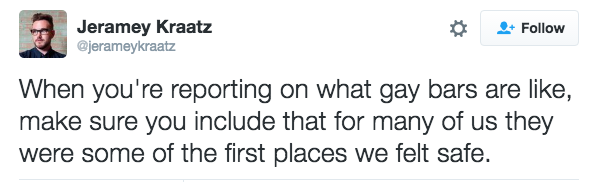

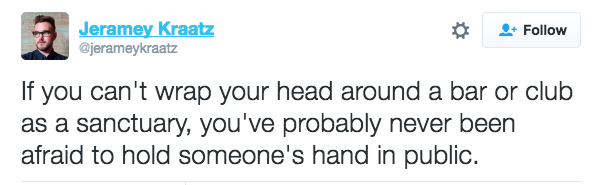

There are so many angles and lessons to learn from this event, but I felt compelled to share my opinions on the symbolic importance of the gay bar to myself and the gay community, spurred by these two tweets from Jeramey Kraatz:

Growing up a sexual minority means you were most likely raised by the majority script. This means you likely weren’t taught the skills or coping mechanisms to deal with your sexuality and most definitely homophobia. You live in fear that those you love the most may not understand. Moreover, you go from one day being what you thought of as “typical” and having unrecognized privileges to coming out. In the next moments, many of those privileges are wiped away and you have to re-frame expectations for yourself and what you can do and what is possible … just because of a few words you said out loud.

For many non-heterosexual people, gay bars help us find our way. They are often the most accessible safe spaces available. So much so that they have academically been compared to churches for the LGBT community, complete with rituals, a sense of community, and a routine. Religious scholar Marie Cartier wrote a history of life at gay bars before the Stonewall riots. “The only place that you could be a known homosexual — even though you could get arrested there and it was not safe,” she wrote, “was a gay bar.” Even today, just knowing that they are there is powerful.

I have gone years not really celebrating Pride, but during a week like this you realize why it is there and why we do it and why it is important.

||

This story originally appeared on Sociological Images, a Pacific Standard partner site, as “#Orlando and the Symbolic Importance of Gay Bars.”