There’s a reason welfare programs haven’t completely eliminated poverty.

By Michael Fitzgerald

Paul Ryan. (Photo: Allison Shelley/Getty Images)

On Tuesday, congressman Paul Ryanreleased the House Republicans’ latest anti-poverty plan. Pacific Standard’s Dwyer Gunnthinks the plan marks a significant, positive rhetoric shift for congressional Republicans who have long been unsympathetic to the poor, even as it pushes the same old policies that many on the left and in the center haveargued won’t do much to address poverty.

But is the plan’s rhetoric really that favorably inclined to the poor? Consider the deceptive statistical gymnastics appearing in the plan’s first paragraph, about programs that have undoubtedly helped the poor:

“Americans,” Ryan writes, “are no better off today than they were before the War on Poverty began in 1964.”

On the next page, he elaborates:

Even though the federal government has spent trillions of taxpayer dollars on these programs over the past five decades, the official poverty rate in 2014 (14.8%) was no better than it was in 1966 (14.7%), when many of these programs started. … As President Ronald Reagan once summed it up, “The Federal Government declared war on poverty, and poverty won.”

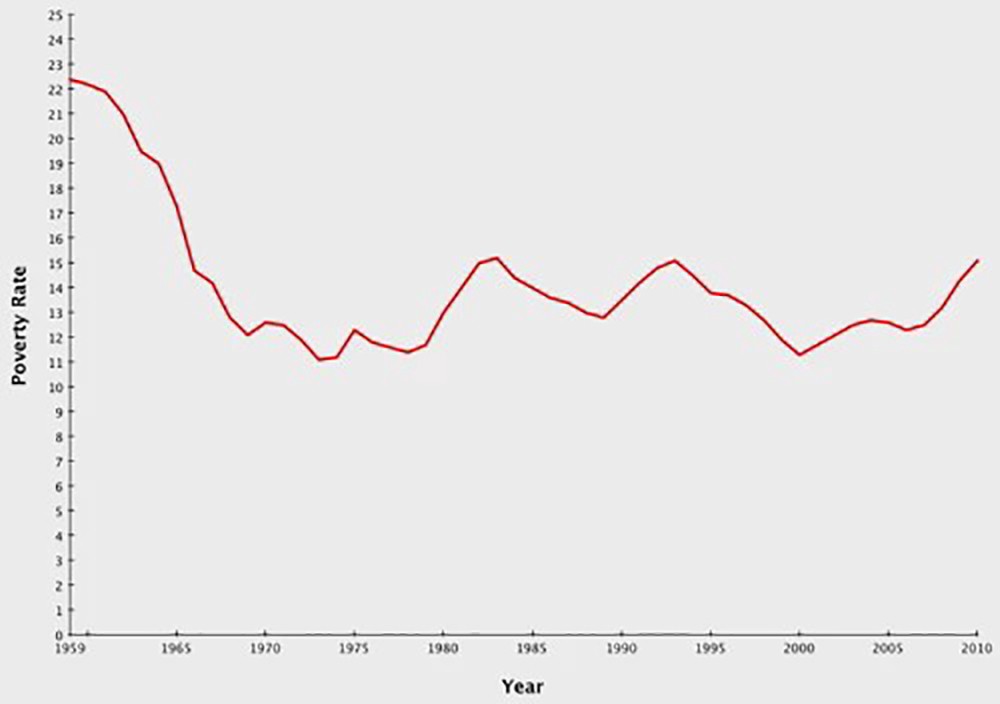

Opponents (and even many proponents) of welfare spending love to trot out the 1966 poverty rate comparison to justify massive overhauls to the system. If the poverty rate remains unchanged from Year One of the War on Poverty, then the War on Poverty must be a failure, goes the logic. But 1966 is the wrong year to compare to today’s poverty rates. Looking further back than Year One of the War on Poverty, as Dylan Matthewsdid in 2012 for the Washington Post, it becomes obvious that the War has had a permanent, positive impact:

(Chart: Washington Post)

The poverty rate hasn’t topped 15 percent since the mid 1960s. It’s fluctuated with business cycles and budget allocations for means-tested welfare programs, but has remained relatively constant in the low teens. The War on Poverty looks more favorable when starting from 1959. The data is a bit murky looking further back than 1959, but the available evidence suggests poverty rates routinely topped 40 percent prior to the 1960s.

So why haven’t welfare programs managed to do better, to completely eliminate poverty? As Gunn points out, it’s partly that many federal anti-poverty programs have been pared back and re-directed toward the working poor since the 1970s, leaving the non-working poor to fend for themselves on food stamps and little else. (The sociologists Kathryn Edin and Luke Schaeffer vividly illustrated how the 1996 welfare reform in particular shifted the worst pains of poverty down the income scale in a book last year.) But the continued existence of poverty doesn’t mean the War on Poverty was lost. It just wasn’t finished yet.

||