As the middle class has been shrinking, the productivity of American workers has been climbing, but the workers haven’t been the beneficiaries of their own work. Nowhere is that more obvious than in long-haul trucking.

By Lisa Wade

Tractor-trailer rigs parked at the Petro truck stop on May 29, 2000, in El Paso, Texas. (Photo: Joe Raedle/Newsmakers)

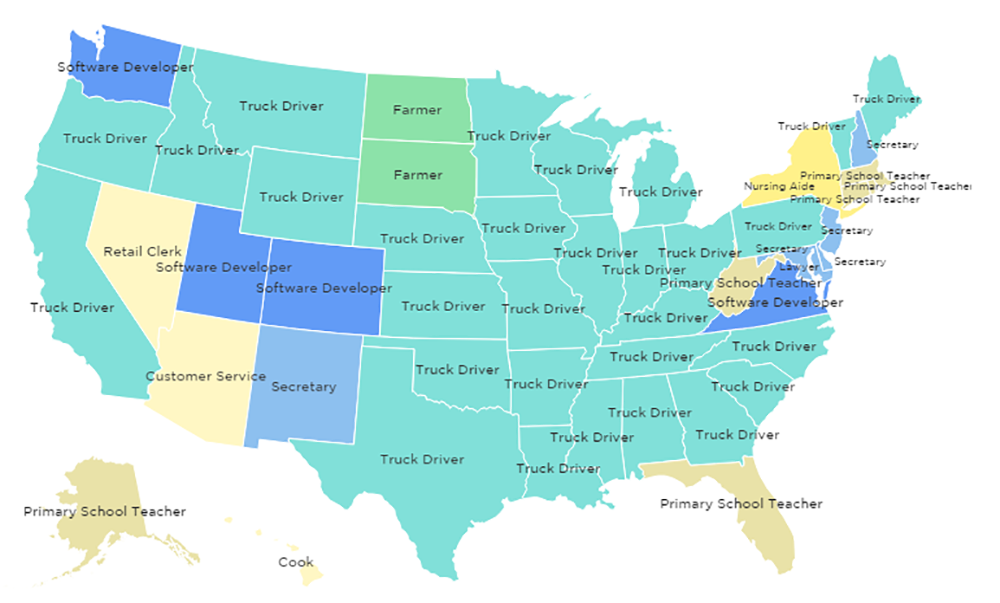

According to this graphic by National Public Radio, “truck driver” is the most common occupation in most states:

But truck driving isn’t what it used to be. In 1980, truckers made the equivalent of $110,000 annually; today, the average trucker makes $40,000. What happened to this omnipresent American occupation?

At The Atlantic, sociologist Steve Viscelli describes his research on truckers. He took an entry-level long-haul trucking job, interviewed workers, and studied its history. He found that the industry had essentially eviscerated worker pay, largely by turning truckers into independent contractors, misleading them about the benefits of this arrangement, and locking them into punitive contracts.

Viscelli argues that few truckers are fully informed as to what it means to be an independent contractor, at least at first. Trucking companies sell them on the idea that they’ll be their own boss and set their own hours, but they don’t emphasize that they will pay significantly more taxes, their own expenses, and the lease on a truck. Viscelli interviews one man who took home the equivalent of 50 cents an hour one week; another week he’d ended up owing the company $100. As independent contractors, he writes, truckers “end up working harder and earning far less than they would otherwise.”

If truckers want to get out of these contracts, the companies can hold their lease over their heads. Truckers sign a years-long contract to lease their truck along with a promise not to work for anyone else. If the contract is violated, the worker is on the hook for the entire lease. This could be tens of thousands of dollars, so the trucker can’t afford to quit. He’s no longer working, in other words, to make money; he’s just working, sometimes for years, to avoid debt.

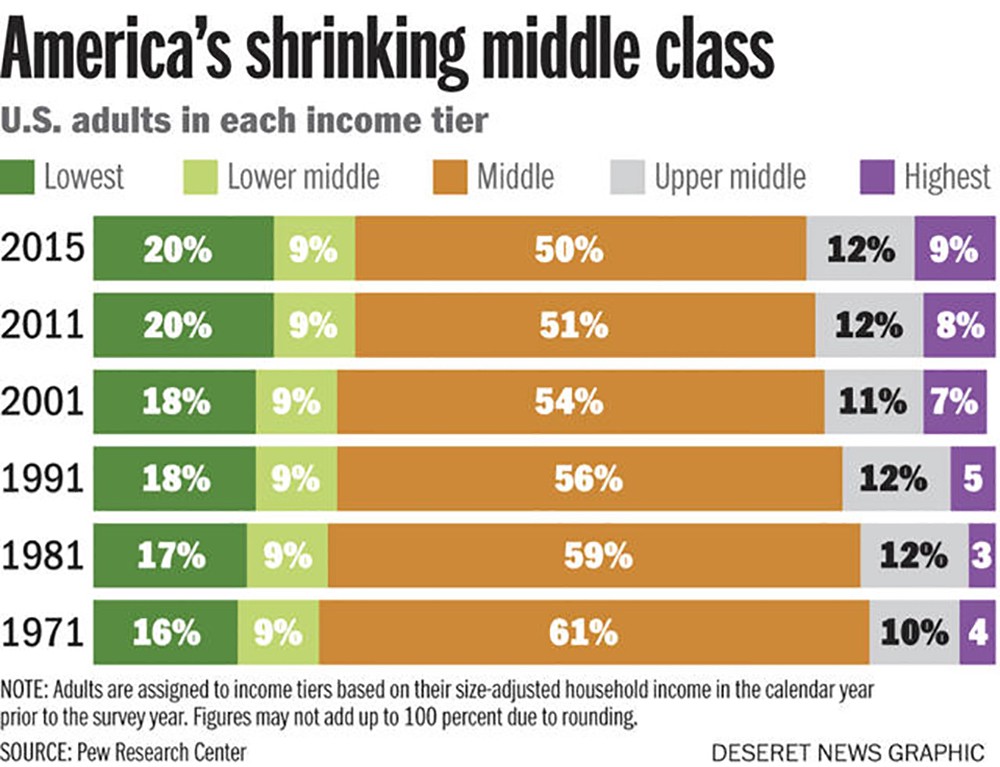

The decimation of this once strongly middle-class job is just one story among many. Add them all up — all of those occupations that no longer provide a middle-class income, and the rise of lower-paying jobs — and you get the shrinking of the middle class. Since 1970, fewer and fewer Americans qualify as middle income, defined as a household income that is between two-thirds of and double the median, or middle, household income.

You can see it shrink in this graphic by the Deseret News using data from the Pew Research Center:

Part of the reason is that we have transitioned to an industrial economy to one that offers jobs primarily in service (low paying) and knowledge/information (high paying), but the other part is the re-structuring of work to increasingly benefit owners, operators, and investors over workers. As the middle class has been shrinking, the productivity of American workers has been climbing, but the workers haven’t been the beneficiaries of their own work. Instead, employers have just been taking a larger and larger share of the value added that workers produce.

Check out this figure from the Wall Street Journal with data from the Economic Policy Institute:

Between 1948 and 1973, productivity and wages increased at close to the same rate (97 percent and 91 percent, respectively), but between 1973 and 2014, productivity has continued to climb (increasing by 72 percent), while wages have not (increasing by only 9 percent).

This is why so many Americans are struggling to stay afloat today. We’ve designed an economy that makes it ever more difficult to land in the middle class. Trucking isn’t the job it used to be, that is, because we aren’t the country we used to be.

||

This story originally appeared on Sociological Images, a Pacific Standard partner site, as “The Trucker, His Downfall, and the U.S. Economy.”