You can argue with what someone says about the facts, but you can’t argue with what they say about how they feel.

By Jay Livingston

What do you think? Is Bernie Sanders too idealistic? (Photo: Ethan Miller/Getty Images)

Historian Molly Worthen is fighting tyranny, specifically the “tyranny of feelings” and the muddle it creates. We don’t realize that our thinking has been enslaved by this tyranny, but alas, we now speak its language. Case in point:

“Personally, I feel like Bernie Sanders is too idealistic,” a Yale student explained to a reporter in Florida.

Why the “linguistic hedging” as Worthen calls it? Why couldn’t the kid just say, “Sanders is too idealistic”? You might think the difference is minor, or perhaps the speaker is reluctant to assert an opinion as though it were fact. Worthen disagrees.

“I feel like” is not a harmless tic…. The phrase says a great deal about our muddled ideas about reason, emotion and argument — a muddle that has political consequences.

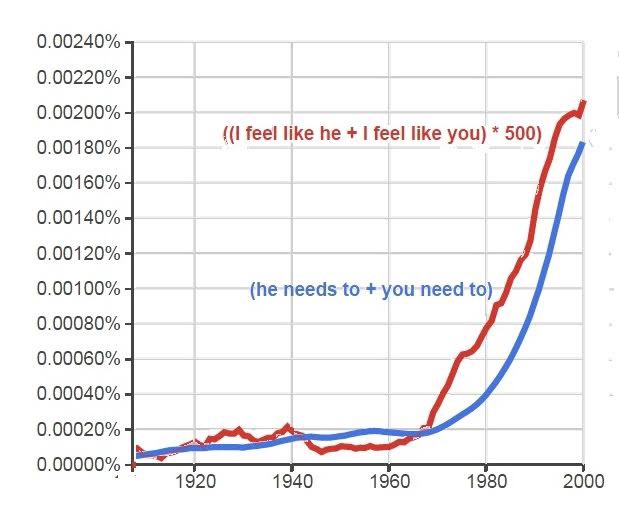

The phrase “I feel like” is part of a more general evolution in American culture. We think less in terms of morality — society’s standards of right and wrong — and more in terms of individual psychological well-being. The shift from “I think” to “I feel like” echoes an earlier linguistic trend when we gave up terms like “should” or “ought to” in favor of “needs to.” To say, “Kayden, you should be quiet and settle down,” invokes external social rules of morality. But, “Kayden, you need to settle down,” refers to his internal, psychological needs. Be quiet not because it’s good for others but because it’s good for you.

Both “needs to” and “I feel like” began their rise in the late 1970s, but Worthen finds the latter more insidious. “I feel like” defeats rational discussion. You can argue with what someone says about the facts. You can’t argue with what they say about how they feel. Worthen is asserting a clear cause and effect. She quotes George Orwell: “If thought corrupts language, language can also corrupt thought.” She has no evidence of this causal relationship, but she cites some linguists who agree. She also quotes Mark Liberman, who is calmer about the whole thing. People know what you mean despite the hedging, just as they know that when you say, “I feel,” it means “I think,” and that your are not speaking about your actual emotions.

The more common “I feel like” becomes, the less importance we may attach to its literal meaning. “I feel like the emotions have long since been mostly bleached out of ‘feel that.’”

Worthen disagrees: “When new verbal vices become old habits, their power to shape our thought does not diminish.”

“Vices” indeed. Her entire op-ed piece is a good example of the style of moral discourse that she says we have lost. Her stylistic preferences may have something to do with her scholarly ones — she studies conservative Christianity. No “needs to” for her. She closes her sermon with shoulds:

We should not “feel like.” We should argue rationally, feel deeply and take full responsibility for our interaction with the world.

||

This story originally appeared on Sociological Images, a Pacific Standard partner site, as “‘I Feel Like’ and the New Individualizing of Morality.”