By Elijah Hurwitz

(Photo: Elijah Hurwitz)

Night falls over Porter Ranch, an affluent neighborhood in Los Angeles, and the surrounding Aliso Canyon on February 2, 2016. The Southern California Gas Company finally capped a leaking natural gas well in the canyon on February 18, though the blowout was made public four months earlier, in October.

While many residents chose to stay in their homes during the leak, thousands of families voluntarily relocated at the expense of the gas company due to illnesses and side effects allegedly caused by chemicals and carcinogens spewing from the ground. Despite the blowout being sealed, many families returning home have experienced the same health issues they fled in the first place such as nosebleeds, headaches, and nausea, leading many to believe that chemicals still linger inside homes.

A “No Trespassing” sign blocks access to Aliso Canyon, where the Southern California Gas Company recently sealed the largest methane gas leak in United States history after it was first reported leaking in October 2015. The leak was caused by faulty safety valves on natural gas storage wells owned by the company (a subsidiary of Sempra Energy) that were first built over 50 years ago. Multiple lawsuits have been filed and the leak has prompted federal and state legislation, as well as repeated protests from local residents.

Andrew and Jennifer Krowne relax in a common area of a Marriott Hotel in Thousand Oaks, a 30-minute drive from their home in Chatsworth. The couple has five children and have been living in hotels for almost four months because of the gas leak.

Andrew is an accountant who spends his free time sharing knowledge and encouraging activism in a closed Facebook group for Porter Ranch residents affected by the gas blowout. “Our trigger to move away to the hotel was really Jennifer,” he says. “She had dizziness, migraines, she developed a thyroid issue. Even that mystery went on for months. Then you have the younger children who have a hard time communicating, and all of the sudden you get ‘I have a headache mommy’ … but wait, you’ve never had headaches before.”

“We spent two days up in Mammoth in the fresh air with my dad and, after two days, literally all felt better,” Jennifer says. “Then it took just two days to go back downhill because as soon as we arrived home we felt fine, but two days later, our five-year-old started having migraines throughout the day and night. A little five-year-old shouldn’t be in this much pain for no reason.”

Jennifer: “Justice here isn’t just financial. Shut down the facility. Just get rid of it. The gas company has been irresponsible, and hurt a lot of people and disrupted lots of lives. And for what? The big dollar. They could’ve shut it down and re-opened the facility once they figured it out, but they chose to carry on in their merry way because none of the executives lived in the area.”

Andrew: “The doublespeak is staggering … you have AQMD [the South Coast Air Quality Management District], which people are suspicious of. You have DOGGR [the Division of Oil, Gas, and Geothermal Resources], who people are totally skeptical of. You figure the other regulatory boards are in the pocket of Sempra Energy, the billion-dollar conglomerate that owns the Southern California Gas Company. It’s all corrupt. If the gas was black smoke, instead of invisible, people would’ve been up in arms about this like crazy.”

Jennifer: “I’m a stay-at-home mom, so there’s nothing I could do to get away from it. We had to call a nanny to help because I was getting so nauseous. I even got scared to drive a car.”

Andrew: “It’s either got to be super regulated, or the things have to go. And it’s not just the Southern California Gas Company. The oil has to go. Anyone who does anything up there in the canyon has to go, because it isn’t safe. You know, we don’t have money. This is the stereotypical David vs. Goliath, armies of lawyers and billions of dollars versus a grassroots group that has nothing but their voices.”

Jennifer Krowne prepares frozen milk in the hotel room in Thousand Oaks her family has been sharing for over two months at the expense of the Southern California Gas Company. Despite the family of seven being cramped into two adjoining rooms, they are determined to stay in hotels until public-health officials declare it safe to return home.

“There was a fairly irresponsible ABC reporter who found a woman at a Starbucks in Porter Ranch the other day who turned out to be a real estate agent, and she said, ‘All these people just need to come back home already because they’re just taking advantage of the situation,’” Andrew, Jennifer’s husband, says.

“Oh right, because $45 for food and having your lives disrupted to live out of a hotel is so worth all of this trouble, right?” Jennifer adds. “I’ve missed out on Thanksgiving because I was sick. We barely got a tree up in the hotel room for Christmas just so our kids had some sense of normalcy. We’ve had to do our kids birthdays here in the hotel. We had to keep making trips back and forth to get clothes, soaps and shampoo, and school supplies”

Jennifer: “It’s not necessarily the gas; it’s the chemicals they lied about, the benzene and other carcinogens in the well. It was one of those eye-opening things; we were about to go back, and slowly going back to our house for a few hours at a time to clean up and prepare to move back, and one night the kids were there with my mom who was watching them … and my daughter woke up twice that night and threw up, and then you’re thinking, ‘Well is it just the gas, or is my kid just sick? But being that there’s five kids, surprisingly we’re a pretty healthy family. About five days later they read the benzene levels were at 2.4. Now, the legal limit for Benzene is under one, and it was at 2.4 that day. Now looking back I’m like, well, that could have been the reason my daughter threw up twice. Everyone’s mad at the gas company because they can get away with things and just say, ‘Your kid’s probably just sick.’”

Andrew: “There’s no trust of the gas company or regulatory boards. The only group that’s been trustworthy or feasible testing program is the University of California — Los Angeles. The department of public health didn’t know what to do. They basically merged with UCLA to fund their testing.”

Jennifer: “What’s come out clearly, is this facility leaked before the blowout. You have to look at the language the gas company uses. They talk about air levels returning to ‘pre-leak’ levels. What people are starting to realize is that even as of a month ago there were 66 leaks. They’ve just had it return to whatever those levels were. The problem is we only know maybe 10 of the potentially hundreds of chemicals we were exposed to because it’s proprietary and the gas company won’t release it. So we don’t even know what we’re testing for. The leaks are supposed to be resolved. They are not.”

Andrew: “So we still have air-quality issues, and a bigger issue is that everything that was spewed is in the environment now, in trees, on the ground, in your house. They’ve already talked about smaller-than-dust-size particles that can’t be seen. So we don’t know what we’re looking for, but it’s been admitted that it’s around and coated everything. So how are they treating that portion of it? You gotta fix the air, you gotta prove that the ground and homes are clean and safe, and do that over however many square miles of the north valley that you have to handle, and do it in a manner that people believe you when you release results as independently as possible.”

Jennifer: “What’s hard is we have really good friends who turn their noses up at us because they aren’t getting sick. We dealt with lots of close friends who just blindly trusted everything was fine because the gas company said it was fine, and it took some of them four months to where they finally got sick enough to leave.”

David Overton, a 34-year-old software engineer, looks toward his home of five years in Porter Ranch. Citing health concerns for their three children, he and his wife decided to relocate to a hotel until the area is deemed safe again. “My wife and I grew up poor,” he says. “We had to work our entire lives to live here. We’re not sure if it will ever be the same in Porter Ranch, not to mention the impact on home values. People are pretty pissed off about it.”

Alan and Sandy Crawford of Granada Hills join a protest outside of Southern California Gas Company offices on March 22. “The breaking point for us was when we returned home and the kids got sick again. In the hotel we kept up with all the protests and events on Facebook and everything, but it was easy to be removed from it all,” Sandy says. “Once we got back and the nosebleeds started happening again, we decided enough was enough.” Sandy is holding a sign showing their son Diesel with a bloody nose.

Sandy, Chancellor, Diesel, and Alan Crawford stand outside their home in Granada Hills, which they have temporarily vacated due to nosebleeds and other health issues related to the nearby gas leak. Depending on the winds in the canyon, many communities other than Porter Ranch also reported health issues.

“We’ve lived here five years. It’s a great place to raise kids. We don’t want to leave,” Sandy says. “We’re still paying for the hotel because we don’t feel safe fully moving back home yet. We want the gas company to cover our cleaning expenses, the hotel, etc.”

“The regulations have to change,” Alan says. “I knew as soon as I heard that [Governor] Jerry Brown’s sister was on the board of directors for the Southern California Gas Company that’s why they dragged their feet for so long.”

Jitender Singh looks into the back of a moving truck as office supplies are packed up with help from his employees. Singh has run a cyber-security firm out of his house in Porter Ranch for years, but finally decided to relocate temporarily because of the gas leak. “My wife was having symptoms, and a few of my employees complained about feeling sick, so it was time to go,” he says.

University of California-Davis scientist and pilot Stephen Conley steps over cables transferring data from instruments on his plane at Van Nuys airport on January 21 after making another flight over Aliso Canyon to measure methane emissions from the gas leak.

Conley was one of the first scientists to sound alarms to the public about the massive scale of the leak and has been making flights for several weeks to gather data. The flight path goes through windy canyons and heavy turbulence before reaching the invisible cloud of methane and its accompanying foul-smelling compound mercaptan, which is a chemical added to make the odor of natural gas detectable. “I’ve had seven people, other researchers mostly, join me on the flights, and all seven of them have gotten sick on the ride,” he says. “I guess I’ve got a strong stomach.”

Doctor and activist Leah Garland affixes a gas mask at a rally on January 16 demanding the shut down of the Aliso Canyon oil and gas wells.

Gurbux Singh of Chatsworth protests on January 23 outside of the Hilton Hotel in Woodland Hills before a public hearing concerning the natural gas storage facilities in Aliso Canyon. Singh says the community will “keep fighting” until the gas storage facilities surrounding nearby residential areas are permanently shut down.

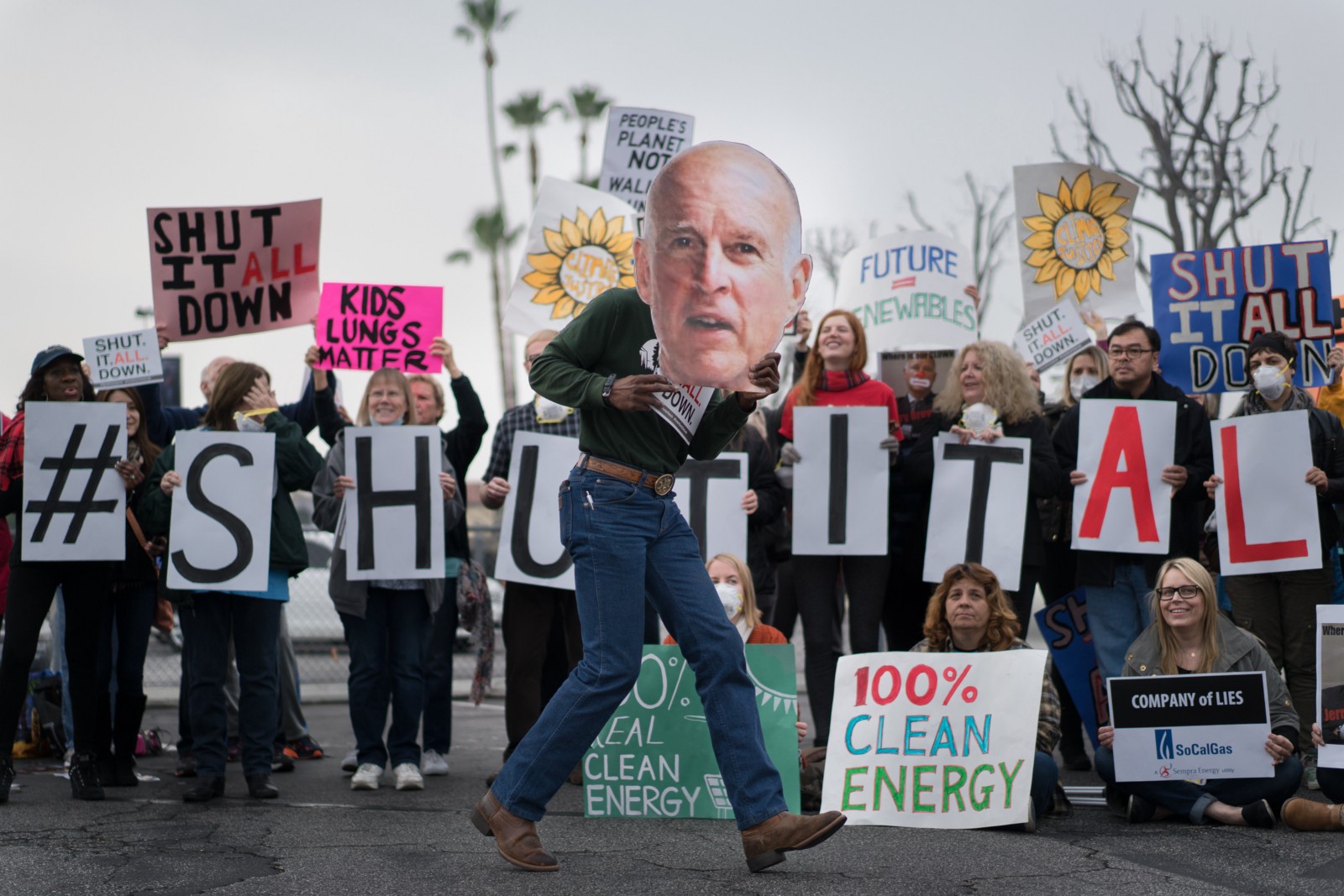

A member of the Sierra Club environmental group dances with a cutout of California Governor Jerry Brown at a Save Porter Ranch rally at Granada Hills Charter School on January 16. Governor Brown has been criticized for responding slowly to the situation, leaving many to speculate that his lack of response was influenced by his sister Kathleen Brown’s position on the board of director’s for the Southern California Gas Company.

Employees and contractors of the Southern California Gas company huddle to discuss the night’s testing plan of chemical emissions on January 14 near the entrance to the Aliso Canyon storage facility where natural gas had been leaking since October.

Ammar Abukarah, a longtime resident of Porter Ranch, flies his recreational drone over Aliso Canyon to get a better view of the leak site. Many hiking paths into the canyon have been blocked by the Southern California Gas Company security contractors, leaving curious residents like Ammar to resort to other means to satisfy their curiosity.

Gary Yamron of Porter Ranch attempts to visualize methane emissions spewing from Aliso Canyon using an infrared FLIR video camera that costs over $10,000. Yamron works for an environmental equipment rental company and happens to live in the Porter Ranch community that has been severely affected by the gas leaks, so he decided to test out the equipment’s infrared capabilities. A video uploaded to YouTube on December 12 used the same model of FLIR camera to record the otherwise invisible giant cloud of leaking methane.

A man from a cleaning service washes the floors of a recently vacated home on Dunure Place in Porter Ranch on March 26. The home, which is up for sale, was vacated by the previous owners because of the gas leak. This is the second time it has been cleaned, according to the man.

The sun sets over the community of Porter Ranch on the evening of January 28, a few weeks before the largest methane blowout in U.S. history was finally capped less than a mile away. Over 112 days, the leak spewed 100,000 tons of methane into the atmosphere, equivalent to the annual greenhouse gas emissions of half a million cars, and the future is still uncertain for many residents who were affected.