She’s appeared in paintings, stood tall as a statue, and helped Abraham Lincoln slay vampires on the silver screen. Now, Harriet Tubman is set to take on the historical province of dead white men.

By Francie Diep

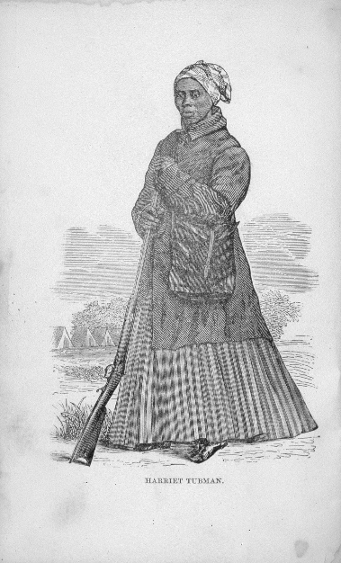

Harriet Tubman. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Harriet Tubman will appear on the $20 bill, Treasury officials announced yesterday. That means she’ll appear over diner counters and in wallets alongside America’s white founding fathers. This marks the first time Tubman will get commemoration of this particular sort, but not the first time her image has driven and inspired Americans.

Below, we’ve got a quick history of Harriet Tubman in American art and pop culture. The examples come from a fascinating paper by women’s studies professor Janell Hobson, published in 2014 in the journal Meridians: Feminism, Race, and Transnationalism. Hobson’s examples highlight not just Tubman’s remarkable staying power throughout American history, but also how long past due Tubman is for a national tribute.

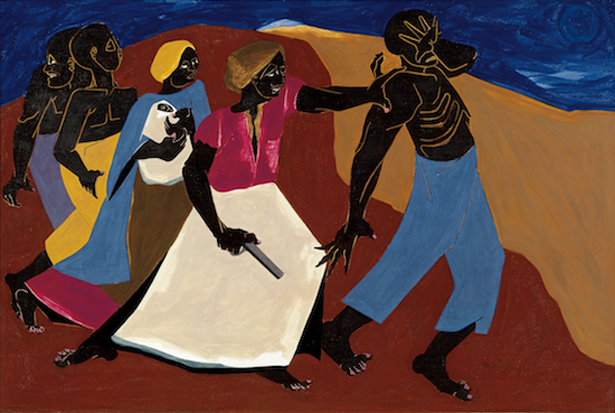

Tubman the Armed Revolutionary

One of the early iconic images of Tubman was, in fact, published during her lifetime, in Sarah H. Bradford’s 1869 book, Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman. The drawing depicts Tubman standing with a rifle, the firearm meant to underscore her service as a spy, scout, and nurse during the Civil War.

Published in 1869, the drawing was the start of a long tradition of Tubman-themed art, much of it showing her as a militant hero—an image that Tubman herself pushed in hopes of receiving a veteran’s pension (it wasn’t until 1899, 34 years after the end of the Civil War, that the government granted her request). Meanwhile, allies sold copies of Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman to help support her.

(Painting: Jacob Lawrence)

Later, the idea of the armed, militant Tubman morphed from being a symbol of patriotism to one of revolution. One famous series of Tubman-centered paintings, by Jacob Lawrence, is full of thick lines, bold colors, and a big, strong-looking Tubman. (In real life, she was “very short and petite,” biographer Kate Clifford Larson writes.) In one of Lawrence’s most moving paintings, Tubman holds a pistol while encouraging/pushing/touching an escaped slave, who covers his face with his hand. During her time as a conductor on the Underground Railroad, Tubman was known to have threatened her charges with a gun at least once when they wanted to quit or go back; she couldn’t afford to let one of them return and possibly be tortured into revealing her route and methods.

Lawrence’s paintings “magnified Tubman into an image of strong black womanhood and Amazonian folk hero,” Hobson writes. She would remain a hero for generations to come: “Tubman modeled for us what resistance and radical action looked like in the past and what we might model for own present and future.”

Tubman the Feminist Icon

During the Civil Rights era, as artists grappled with the issues of the day, they once again tapped the Tubman image. She became a symbol of both racial and gender equality. Artist Faith Ringgold included text from one of Tubman’s speeches in a series of paintings called Feminist Landscape, made in 1972, and numerous writers emphasized the fact that women like Tubman have been leaders in the fight for emancipation and civil rights as much as men.

Tubman Today

In recent years, Tubman has often appeared in children’s books, which can be both infantilizing and powerful, Hobson argues. Tubman gets portrayed as fairly flat and mythical — an uncomplicated hero for kids— but she also gets to take her place in the minds of young and impressionable Americans.

From Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman

.

(Image: Forgotten Books)

Tubman has also appeared in some notably weird modern art. She shows up to help in the 2012 movie Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Slayer. And she subverts mainstream consumer culture in a video series published in 2011, “Black Moses Barbie,” where her doll comes with — you guessed it — a rifle accessory.

A National Tubman

Despite her cultural appeal, a national monument has remained elusive. Hobson notes that, while there are public statues of Tubman, they’re only located in predominantly black neighborhoods, suggesting this crucial figure in American history remains segregated from the national story. There is no big, bronze Harriet Tubman on the National Mall.

That’s where the $20 bill comes in. When Tubman gets printed on America’s paper money, she’ll take a place traditionally occupied by white founding fathers. She’ll be there because she embodies what those men are supposed to: the defense of freedom and democracy.

Throughout its history, American democracy has been exclusive, flawed, and undemocratic, which makes the work of those who have been disenfranchised by the government all the more important. In that history, Salamishah Tilletwrites, “black women, not the founding statesmen, emerge as the true progenitors and guardians of democracy.”

||