The Department of Labor just announced a new rule requiring financial advisers to put their clients’ interests first.

By Dwyer Gunn

A sign hangs over Morgan Stanley’s headquarters in New York City. (Photo: Mario Tama/Getty Images)

On Wednesday, the Department of Labor (DOL) announced a new rule requiring financial advisers who handle IRAs and 401(k)s to act in their customers’ best interest. That this wasn’t already a mandate may come as a shock to millions of Americans. But, in fact, most investment professionals who deal with these types of accounts are currently only required to recommend investments that are “suitable” for their clients’ financial needs. This loophole means advisers can recommend products that offer a higher commission, even if the products charge higher fees to investors and produce lower returns.

“Many investment professionals, consultants, brokers, insurance agents and other advisers operate within compensation structures that are misaligned with their customers’ interests and often create strong incentives to steer customers into particular investment products,” explains the DOL’s fact sheet on the new rule. “These conflicts of interest do not always have to be disclosed and advisers have limited liability under federal pension law for any harms resulting from the advice they provide to plan sponsors and retirement investors. These harms include the loss of billions of dollars a year for retirement investors in the form of eroded plan and IRA investment results.”

The DOL first proposed the rule (formally known as the fiduciary rule) last year. The regulation has faced fierce opposition from both the financial industry, which has argued that the rule will ultimately increase costs for middle-class investors, and from conservative politicians, who oppose the regulatory burdens it will impose and describe it as “Obamacare for financial planning.” (It has received extensive support from Senator Elizabeth Warren.)

A change, however, is clearly needed. Over the last 40 years, the manner in which most Americans save for retirement has changed dramatically, and regulations have simply failed to keep up. In 1974, when the Employee Retirement Income Security Act was first passed, most people’s retirement savings took the form of employer-sponsored traditional pension funds, which required little financial sophistication or input from employees, and were handled by the kind of professional investment managers who are legally required to act in their clients’ best interests.

Today, pensions are a thing of the past. The majority of families who manage to save anything at all for retirement, relying on defined contribution plans and IRAs, are left to navigate a confusing maze of options on their own. As a result, many of these individuals become particularly vulnerable to irresponsible financial advice.

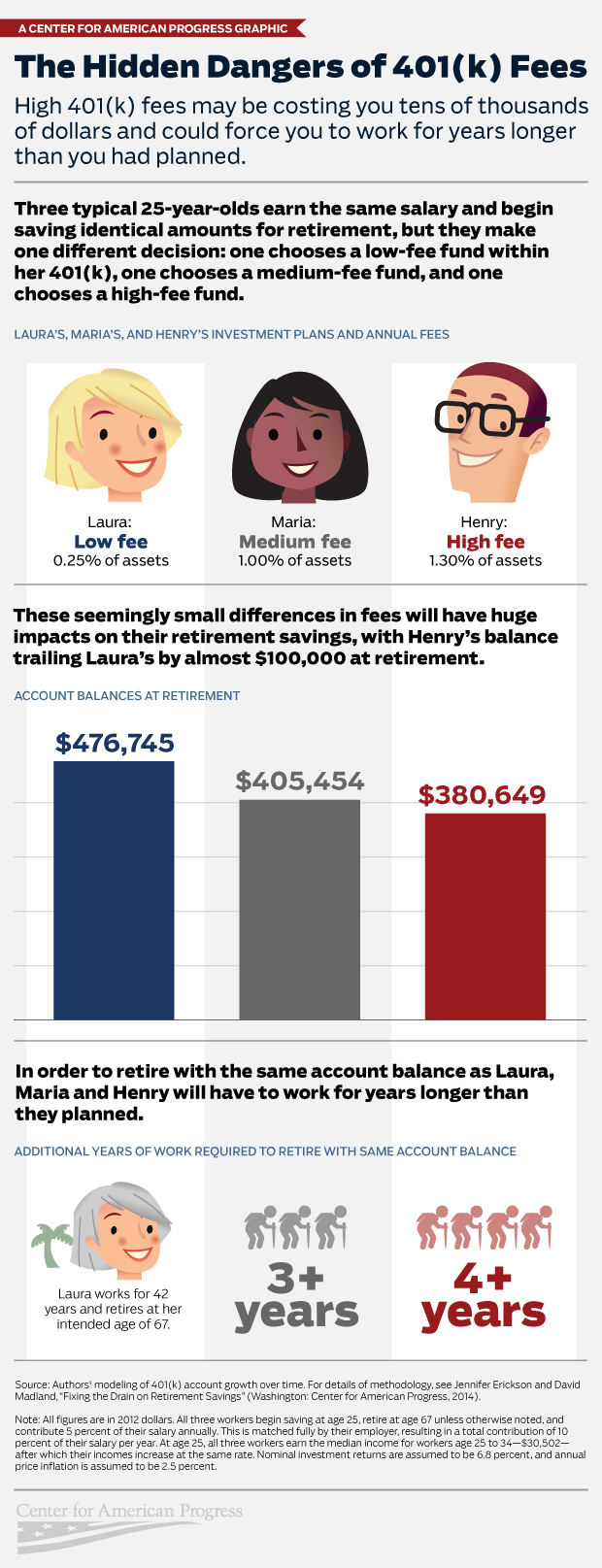

(Graphic: Center for American Progress)

Researchers have consistently found that the funds recommended by advisers with conflicts of interest charge higher fees and deliver lower returns. Oftentimes, the difference between various investment products can seem inconsequential — the average investor may not be too alarmed when their adviser suggests they invest their savings in a fund that charges a one percent management fee. But small differences can have big consequences over the long run.

The infographic to the left, from the Center for American Progress, compares the ultimate retirement savings of three individuals paying 0.25 percent, one percent, and 1.30 percent asset management fees.

Last year, the Council of Economic Advisers released a report on the economic consequences of the investment advice provided by advisers with conflicts of interests. They concluded that “[s]avers receiving conflicted advice earn returns roughly 1 percentage point lower each year.” Such a difference could reduce a retirees’ savings by more than 25 percent over 35 years. In total, the CEA estimates that “conflicted advice costs Americans about $17 billion in foregone retirement earnings each year.”

Over half of all Americans do not have enough saved for retirement, according to the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College; the percentage is much higher for low-income Americans. The fiduciary rule may seem like a small, esoteric change, but it will make investment saving easier for millions of Americans.

||