If there’s one thing that the candidacies of Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders have made clear, it’s that people in America are not happy with the status quo. They’re not happy with the economy, they’re not happy with the rising cost of health care and college, and they’re not happy with a modern world in which previously well-paying jobs can now be performed by computers or workers overseas.

Trump supporters are overwhelmingly white, lack college degrees, and are drawn from exactly the kinds of places that have been decimated by a rapidly changing economy that favors coastal computer coders, doctors, and financiers over miners and factory workers. (Although recent events suggest his base is growing.)

Sanders, meanwhile, draws his support primarily from young voters who have gravitated toward his big plans and perceived independence from the standard political establishment. Both demographics illustrate just how widespread the frustration with our current economic model has become.

Over the last 40 or so years, the real wages of most Americans have essentially stalled, with the exception of a brief period of prosperity in the late 1990s. For much of the 1980s and first half of the ’90s, the trend primarily affected middle- and lower-income American workers, but since the beginning of this century, workers across almost all of the income distribution have seen their wages stall. In fact, the economic boom of the late 1990s was the only time in recent history when Americans’ wages increased.

Where did we go wrong?

To understand what happened to wages in America, you have to go way back, before 1994’s North American Free Trade Agreement, before China joined the WTO in 2001, before robots and iPhones, before hedge funds and private equity, before banks become too big to fail and their executives exited the stage with multi-million-dollar golden parachutes. Before any of that, to the golden years of the 1950s and ’60s, in the wake of the Great Depression and wartime rationing, when Americans wanted cars and houses and dishwashers. As factories innovated to meet rising consumer demands, productivity, defined by economists as the amount of output generated by an hour of labor (and a significant determinant of wage growth), also increased dramatically. Organized labor was strong, and everyone — management, labor, and the government — wanted to keep the production lines moving.

“There was a sense coming out of the war, with all this demand for consumer goods, that there was a lot of money to be made if you could keep production going,” says Frank Levy, an economist and professor emeritus at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “And so what that meant was no strikes, and so that then led to these kinds of negotiations … that said there are going to be cost of living increases, there are going to be productivity gains [built into wage increases], and the quid pro quo is you don’t strike so we can keep production going.”

During the post-war era, the general strength of the American economy produced benefits for Americans of all different income levels. But by the 1970s, fracture lines had begun to appear. Productivity growth slowed, and a series of oil price shocks caused inflation to skyrocket.

“Wages stopped growing and then high school graduate wages fell through the floor. That sets the stage for what happens after that.”

While coastal, urban economies struggled in the face of the unprecedented, double-digit inflation, the center of the country, which was dominated by agriculture and heavy manufacturing like the automobile and steel industries, continued to thrive into the ’70s. Thanks to the dollar’s low value abroad, international demand for American-made durables was high and exports were strong.

“The center of the country was the place to be, but the byproduct of all of that was all this inflation” Levy says.

By the end of the 1970s, however, inflation had become too high to stomach, and President Jimmy Carter nominated Paul Volcker as chairman of the Federal Reserve. Under Volcker’s leadership, the Federal Reserve began aggressively raising interest rates with the goal of breaking inflation, whatever the cost. Between 1979 and 1984, the value of the dollar increased by approximately 55 percent. Exports, and the earnings of the high school graduates who produced those exports, fell through the floor. Compounding these macroeconomic forces was a new policy model of supply side (or “trickle-down”) economics that emphasized pro-business policies, low taxes, market deregulation (particularly of the financial sector), and a smaller role for the federal government.

“You had what had been the hall of unionized blue-collar high-school workers, all the durable manufacturing belt from Wisconsin down through Baltimore,” Levy says. “And it was just wiped out…. So on the one hand, wages stopped growing and then high school graduate wages fell through the floor. And that sets the stage for what happens after that.”

What happened after that was an economy that slipped and stumbled through multiple periods of high unemployment and the emergence of two deeply disruptive economic forces: globalization and technology, both of which displaced low- and middle-income workers and drove a growing preference for highly skilled and highly educated workers.

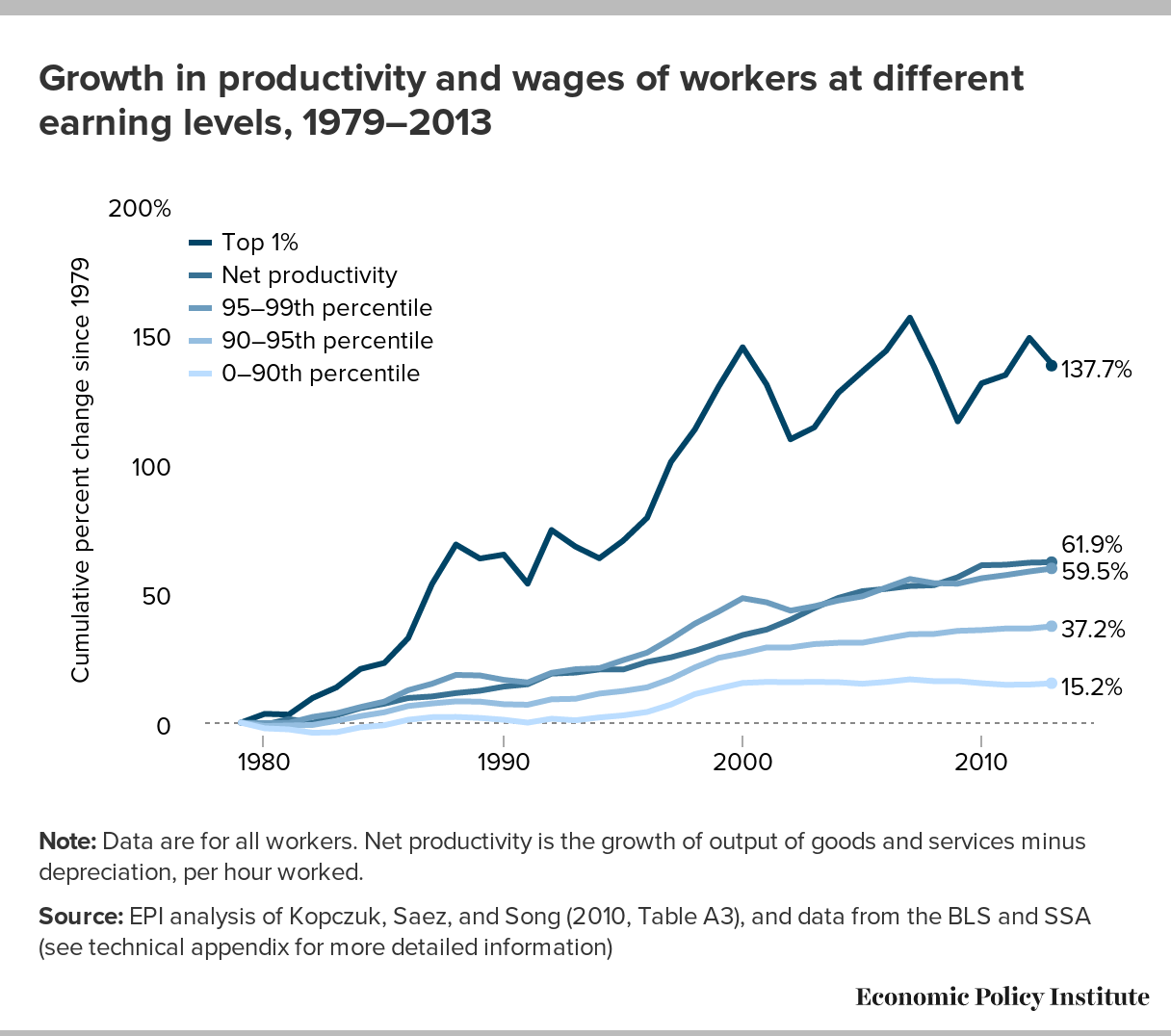

This chart from the Economic Policy Institute, a liberal think tank, illustrates the grim reality of wage stagnation in America:

“The stagnation has been very broad-based since around 2002,” says Larry Mishel, the president of the EPI. “And when I say broad-based, I mean the bottom 80 percent of the workforce, both college graduates and high school graduates, both white-collar workers and blue-collar workers. It’s not a phenomena solely due to the fact that we had a Great Recession, and I don’t want people to think that. This is very long-standing.” Economists disagree somewhat about technology’s effect on employment and wages, but there’s widespread agreement that globalization has indeed harmed middle-income American workers.

Trade, especially free trade agreements like the North American Free Trade Agreement or the hotly debated Trans-Pacific Partnership, has emerged as a flashpoint in this election. On the left, Sanders has repeatedlyattacked Hillary Clinton for her (and her husband’s) stance on trade. “I voted in complete opposition to every one of these disastrous trade agreements,” Sanders said at a Michigan campaign rally. “Secretary Clinton voted for virtually all of them.”

Trade opposition has also, of course, formed the backbone of Trump’s economic policy platform. Trump has promised to renegotiate all foreign trade deals, put hedge fund manager Carl Icahn in charge of trade negotiations with China, make Apple manufacture its “damn computers” in the United States, and impose a 35 percent tax on Ford cars manufactured outside the country (the company has plans to build a plant in Mexico).

In reality, economists generally agree that NAFTA had a minimal effect on American employment. In fact, the years after NAFTA was passed were the only ones in recent history in which the real wages of most Americans actually did increase. The estimated impacts of the TPP on American employment are similarly minimal. So who or what is to blame for globalization’s effect on wages? The real culprit is China, which joined the World Trade Organization in 2001. In a seminal paper on the topic, the economists Daron Acemoglu, David Autor, David Dorn, Gordon Hanson, and Brendan Price estimated that import competition from China between 1999 and 2011 resulted in the loss of between two and 2.4 million American jobs.

And in a working paper released earlier this year, Autor, Dorn, and Hanson found that the “China shock” had surprisingly long-lasting effects on certain segments of the American economy. “Adjustment in local labor markets is remarkably slow, with wages and labor-force participation rates remaining depressed and unemployment rates remaining elevated for at least a full decade after the China trade shock commences,” the authors concluded. “Exposed workers experience greater job churning and reduced lifetime income.”

The U.S. is not the only developed country that has faced the challenges of globalization and technology in recent years — countries like Germany and Sweden, for example, have grappled with the consequences of offshoring and outsourcing. But American workers have had a profoundly more painful experience than their European counterparts thanks to a variety of institutional factors. For starters, the economic forces and policy decisions of the 1980s dealt a critical blow to America’s private sector unions, which they’ve still not recovered from. Absent a strong economy, collective bargaining (which is still a dominant force in most of Europe) is one of the few ways workers are able to successfully advocate for higher wages and other protections (paid leave, overtime protections, increases in the minimum wage, and so forth).

Furthermore, the cuts to the social safety net that occurred under Presidents Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton left displaced workers with little to fall back on. Most European countries, by contrast, have more redistributive tax systems and stronger social safety nets. In fact, a number of European countries actually have similar (or even higher) levels of pre-tax inequality as the U.S., but much lower levels of inequality after taxes and transfers are taken into account.

“[T]he idea that somehow everything you see around you is just the result of market forces misses the point that it’s the result of market forces interacting with a particular set of institutions that we have,” Levy says.

And then there’s that oft-maligned one percent. Wage stagnation hasn’t impacted everyone equally; workers at the very top of the income distribution have seen astronomical increases in their earnings.

The debate over whether these increases are actually causing the stagnating wages of everyone else is contentious. Over the last several years, a vocal chorus of liberal economists has argued that any efforts to address wage stagnation in this country must include a discussion of the behaviors of the one percent.

Last year, Joseph Stiglitz, a Nobel Prize-winning economist and former chair of the Council of Economic Advisors, published a book called Rewriting the Rules of the Road,in which he argued that “[s]kyrocketing incomes for the 1 percent and stagnating wages for everyone else are not independent phenomena, but rather two symptoms of an impaired economy that rewards gaming the system more than it does hard work and investment.”

(Photo: Bill Pugliano/Getty Images)

But not everyone believes we can pin America’s economic woes on the rising incomes of the one percent. “I’m not convinced that the growth of the top 1% explains wage stagnation more broadly. We’ve also had anemic productivity growth, so there’s less surplus to go around,” Autor, who has extensively studied the economic effects of trade and technology, writes in an email. “The question to my mind is not whether we should make the 1% less wealthy through various taxes and regulations; it’s rather how we would invest those resources if we had them to create a greater degree of shared prosperity.”

Regardless of their thoughts on this debate, many economists are indeed concerned about how the increase of upper-tail inequality will interact with the growing role of money in our political system. “You have this growing influence of money on politics. Was that there when John Kennedy was elected or when Lyndon Johnson declared the war on poverty? No,” says Richard Freeman, an economist at Harvard University. “You know, James Madison and some of the founding fathers of our country had this view that once you get some inequality, the people that get the money use it to influence the government to let them make more money, and then it’s a hard cycle to break.”

Now that we’ve gotten ourselves into this mess, how should we go about getting out of it?

Contrary to the rhetoric of Trump and Sanders, reneging on our trade deals and returning the U.S. to a protectionist society is wildly unrealistic and would likely provoke economically and diplomatically damaging retaliation from other countries.

While improving America’s education system may not reduce upper-tail inequality, it nonetheless does still have the potential to increase worker’s earnings and well-being. Economists have found enormous returns to teacher quality, and college graduates still earn more than high school graduates by a fairly large margin. It’s also no doubt time to think more creatively about post-secondary education.

“I think we need to think about the skill sets that allow people to do evolving jobs in health care, in technical positions, many of which require real skill sets, but they don’t require a four-year liberal arts training,” Autor said at the Hamilton Project panel last year. “So I think we push too many people toward expensive four-year degrees which either are not as efficient as they could be, or not as appealing as they could be. There are opportunities in … these kind of new middle-school occupations.”

Melissa Kearney, an economics professor at the University of Maryland who studies poverty and inequality, points out that education will likely need to be ongoing in the future. She cites the need for on-the-job training and more agile institutions of higher learning. “The labor market and the nature of jobs will likely evolve very rapidly,” she says. “Will people adapt quickly enough? What we really need to be thinking about is how to educate people while also fostering adaptability.”

Economists like Richard Freeman have also advocated for policies (which Hillary Clinton has supported) that incentivize corporations to implement and expand profit-sharing programs, so more employees can benefit from corporate profits. Researchers have found these kinds of programs boost worker productivity while also benefiting companies. “They’re not doing it to create less inequality, they’re doing it because we have a highly educated workforce, and people can be motivated and incentivized by this to do better,” Freeman says.

Fiscal policy (i.e. government spending) is another useful tool that many economists argue could be better utilized to increase demand and give workers more bargaining power. When unemployment is high, and there are 25 applicants for every job, workers don’t have much ability to negotiate for higher wages. “Low unemployment fuels wage growth, and it does so more for low-wage workers than middle-wage workers, and more for middle-wage workers than for higher-wage workers,” says the EPI’s Mishel.

Despite a monetary policy of very low interest rates, the U.S.’s fiscal policy in recent years (since 2011) has been disturbingly austere — some believe it’s the reason economic recovery has been so slow and unimpressive. “You have a zero interest rate, and you’re not doing infrastructure spending, and running a bigger fiscal deficit? That does not make economic sense to me,” Freeman says. “This is an ideal time to make our roads better, make our schools better, makes our airports first-rate.”

There are also, of course, a number of institutional reforms and policy changes that could be made in the U.S. to ensure a more equitable distribution of prosperity. Tax loopholes that benefit only a wealthy few could be closed, and high earners could be taxed at a higher rate so that the social safety net could be strengthened and expanded. These solutions may not eliminate upper-tail inequality or reverse the structural changes in the economy that have so constrained the wages of the typical worker, but they would dramatically improve the lives of many Americans.

“You don’t need to be angry at the one percent to think that we still might need to raise taxes on them,” Kearney points out. “Not to punish them, but because we need the revenue to deal with some of these challenges.”

It remains to be seen whether the current populist anger over economic conditions will actually result in meaningful change after this election, particularly given the ever-growing influence of political lobbyists. But it’s difficult to imagine the forces that have elevated Trump and Sanders simply fading away after the election.

“I think this is a very useful election because I think that both parties have really kind of turned their back on this issue until recently, and now it’s just making itself heard,” Levy says. “And so that’s the whole point: Unless you make yourself heard, nobody’s going to pay attention to you.”