In 1985, the United States established a program called Lifeline, which provided subsidies to low-income Americans for landline phone service. Over the last year or so, the Federal Communications Commission has been hard at work overhauling and modernizing the program, with a new emphasis on broadband Internet access. Earlier this week, the Obama administration announced its support for the FCC’s plan, which would provide low-income families with a credit of $9.25/month toward their high-speed Internet bill. Both the administration and the FCC hope that subsidizing Internet bills will also financially incentivize providers to improve the dodgy quality of broadband service in underserved areas. The proposal echoes a number of other state and national initiatives to increase high-speed Internet access for disadvantaged, low-income Americans.

“When we talk about digital equity, we need to remember that we’re talking a key part of the answer to many of our nation’s greatest challenges—issues like income inequality, job creation, economic growth, U.S. competitiveness,” Tom Wheeler, the chairman of the FCC said in a speech last month.

There is, indeed, a substantial digital divide in America. According to a brief by the Council of Economic Advisors that accompanied the president’s announcement, slightly fewer than half of poor households have home Internet access, compared to 95 percent of households with incomes in the top 20th percent of the distribution. And there’s little doubt that high-speed Internet access has become a staple of modern life—business communication and transactions increasingly occur online, job searching is more effectively conducted on the Internet, kids are expected to both research and complete homework assignments on the Web, and most employers now expect a high level of digital literacy from their workers.

Internet job searching reduced the length of unemployment by about 25 percent.

But can better high-speed Internet access really help “answer many of our nation’s greatest challenges”?

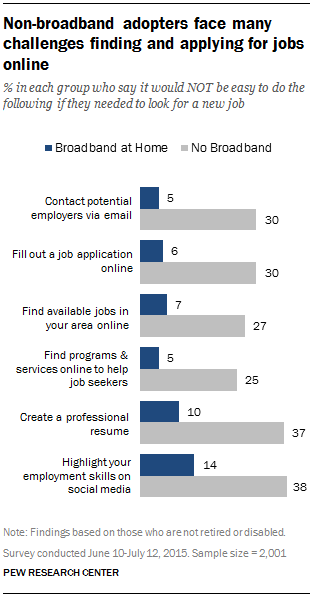

The Council of Economic Advisor’s brief highlights one well-established benefit of home Internet access: It makes job-searching faster and more efficient. A 2011 paper found that Internet job searching reduced the length of unemployment by about 25 percent, and data from the Pew Research Center, published last December, indicates that job seekers without broadband access are at a significant disadvantage when it comes to tasks like filling out online job applications, searching for local jobs, and creating a resume. Aaron Smith, a Pew researcher, points out that “these disparities in access could become a self-perpetuating cycle for financially struggling Americans” if they significantly hamper job search efforts and outcomes.

There’s also some evidence that Internet usage (which would presumably see an uptick with better broadband access) can increase earnings. A 2008 paper published in the American Sociological Review found that workers who used the Internet, either at work or at home, experienced faster earnings growth than those who didn’t. The authors of the study concluded that “some skills and behaviors associated with Internet use were rewarded by the labor market.”

But the evidence on broadband’s ability to spur local economic growth is a bit murkier. Some research seems to indicate that broadband access does encourage growth, but it’s difficult to determine if improvements in broadband access are actually causing local economic growth, or simply occurring alongside it. For example, while a 2014 paper in Telecommunications Policy concluded that high levels of broadband adoption in rural areas were correlated with income growth, the researchers stopped short of claiming a causal relationship (saying instead that a “potential” causal relationship existed).

The relationship between high-speed Internet access and local economic growth also comes with a giant caveat: Broadband access affects different industries, populations, and regions quite differently. In general, industries that are more technology-dependent (finance, business support, etc.) experience greater benefit from improvements in local broadband access than old-school industries like, for example, mining. This is to be expected, of course, but it’s an important truth to keep in mind when considering the realistic likely impacts of improved broadband access in regions that are dominated by a single industry.

It’s also not entirely clear that the economic benefits of better broadband are always felt by local residents. An analysis by Jed Kolko of the Public Policy Institute of California found that, while broadband expansion likely led to large increases in local employment growth, it had no effects on the employment rate of local residents. In other words, the jobs created by local broadband expansion aren’t always filled by local residents. Kolko also found no relationship between broadband expansion and average pay. In fact, expansion was associated with a decline in median household incomes:

In sum, whatever positive effects broadband may have on employment growth, it did not result in either higher employment rates or higher pay for residents in areas where broadband expanded during the period 1999– 2006 period. As described above, these residents may benefit indirectly from employment growth in their county if that growth raises the local tax base or property values, but they do not benefit directly in terms of greater likelihood of being employed or higher earnings or income. Residents who rent, and therefore might have to pay more for housing when property values rise, could possibly become worse off economically from employment growth that raises neither the employment rate nor average pay per employee.

Caveats aside, more affordable high-speed Internet is likely to be a good thing for low-income families, especially as schools and employers increasingly assume that everyone has access to such technology. But it is not, on its own, a panacea for the deeply troubling inequities that currently plague America’s education, health-care, and economic systems.

Lead Photo: (Photo: Michael Bocchieri/Getty Images)