First, the good news: The Affordable Care Act has resulted in a significant increase in the percentage of Americans with health insurance. Last September, the Department of Health and Human Services published a new analysis estimating that 17.6 million previously uninsured people had gained health insurance due to various provisions of the ACA. Similarly, a paper published last summer in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that the ACA’s first two open enrollment periods were associated with improvements in “self-reported coverage, access to primary care and medications, affordability, and health,” findings that are echoed in a recent three-part report from AARP and the Urban Institute.

Now, the bad news: According to a report released last week by the Kaiser Family Foundation, almost three million low-income Americans are still without health insurance due to the Medicaid coverage gap. While middle-class Americans without employer-provided health care have enjoyed significant improvements in health care since the ACA’s implementation, the 2.9 million poor Americans in the Medicaid coverage gap have been left behind and continue to have limited access to the health and economic benefits conferred by health insurance coverage.

The ultimate goal of the ACA was universal health-care coverage for Americans of all income levels. The law laid out three pathways to health coverage: Americans with employer-provided health insurance would keep their existing plans, middle-income Americans without employer-provided insurance would be able to purchase coverage on newly established exchanges (with tax credits for families and individuals below a certain threshold), and low-income Americans would be newly eligible for coverage under a greatly expanded Medicaid.

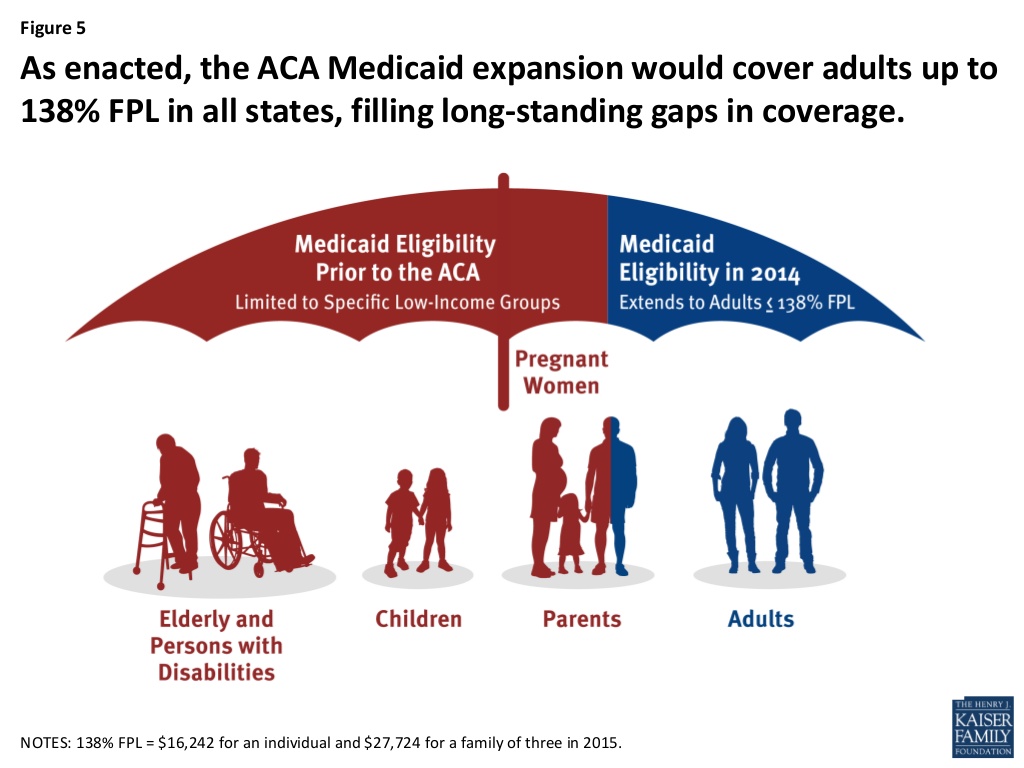

This chart from the Kaiser Family Foundation shows what the ACA Medicaid expansion was supposed to look like:

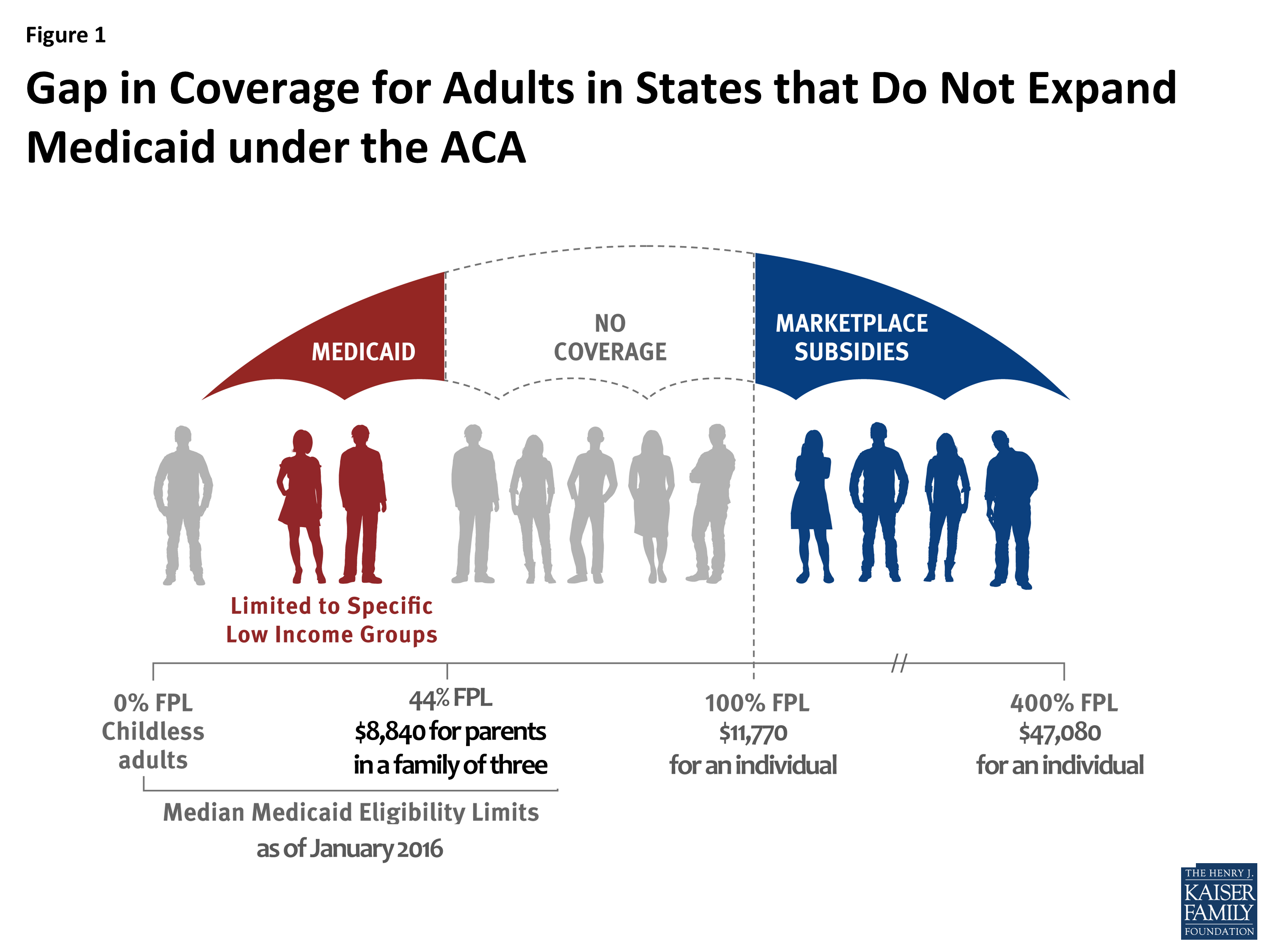

In 2012, however, the Supreme Court struck down a key tenet of the ACA, ruling that the federal government couldn’t compel states to expand their Medicaid programs; the governors of a number of Republican states quickly announced they would not be expanding Medicaid. The result was a devastating gap in coverage in states that chose not to expand Medicaid: Low-income individuals who weren’t eligible for Medicaid under the program’s pre-ACA rules, but who earned too little to qualify for the tax subsidies and credits meant to make health insurance accessible to middle-class Americans, were simply out of luck.

This is how the Medicaid expansion actually went into effect in the states that didn’t expand their Medicaid programs:

Last week’s Kaiser Family Foundation report provides updated estimates on the number of affected individuals. The findings aren’t good: The report estimates that 2.9 million Americans (90 percent of whom live in the South) currently fall into the ACA coverage gap.

Twenty-four percent of those in the coverage gap are parents with dependent children, which is particularly troubling given the sizable body of evidence indicating that providing health-care coverage for low-income parents (via programs like Medicaid or the State Children’s Health Insurance Program) increases the odds that their children will be enrolled in a similar insurance program and improves the medical care their children receive.

Half the adults in the Medicaid coverage gap are employed, according to the Kaiser analysis, and 62 percent are part of a family with at least one working adult, though many work at small firms that aren’t legally required to provide health insurance to employees. “The majority of people in the coverage gap are in poor working families—that is, either they or a family member is employed either part-time or full-time but still living below the poverty line,” the report concludes.

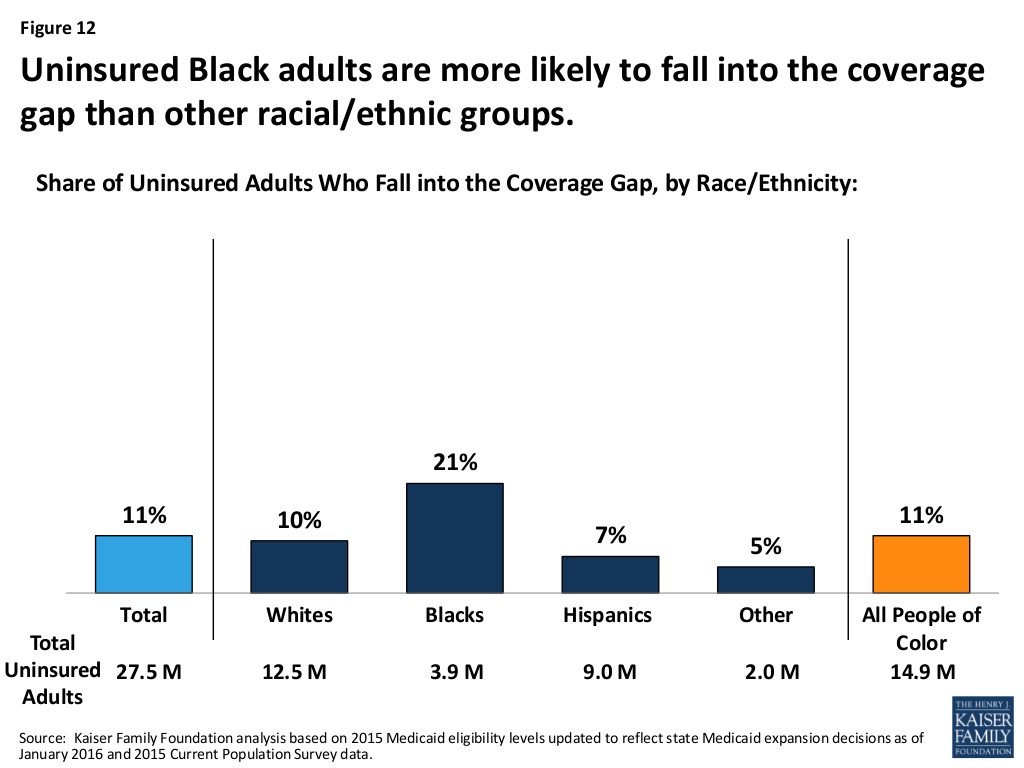

Since many of the Southern states that haven’t expanded Medicaid have large populations of low-income African Americans, there’s also a substantial racial element to the coverage gap. Uninsured African Americans are “more likely to fall into the coverage gap than other racial/ethnic groups,” a disparity that has the potential to worsen racial health inequities in Southern states.

For most of these families, purchasing health insurance without a subsidy is financially impossible, as a stark example from the Kaiser report makes clear:

[I]n 2016, the national average unsubsidized premium for a 40-year-old non-smoking individual purchasing coverage through the Marketplace was $299 per month for a silver plan and $236 per month for a bronze plan, which equates to more than half of income for those at the lower income range of people in the gap and about a quarter of income for those at the higher income range of people in the gap. Further, people in the coverage gap are ineligible for cost-sharing subsidies for Marketplace plans and could face additional out-of-pocket costs up to $6,850 a year if they were to purchase single individual Marketplace coverage.

The consequences of not having health insurance are well-documented and obvious: People delay care, which can result in complications, higher medical costs down the road (for individuals, hospitals, and society), and even death. As Joan Melcher reported for Pacific Standard in 2008, one study by the Urban Institute estimated that 22,000 adults died in 2006 because they lacked health insurance.

Health insurance isn’t a cure-all, as a recent poll on medical debt among the insured from the New York Times and the Kaiser Family Foundation indicates, but its positive effects are hard to debate.