American workers just got a major raise—and it may be their undoing.

On January 1, 14 states officially raised their minimum wages. While that might not seem surprising in places like Maryland and New York, where automatic minimum wage hikes tend to correspond to inflation and the rising cost of the living, this latest increase is indeed markedly different: Twelve of the 14 states mentioned above raised their minimum wages through legislative action during the previous year, as opposed to an automatic adjustment.

In a political climate seemingly dominated by lobbyists and anonymous billionaires, 2015 seemed like a year that democracy won. The public was in support of giving workers a raise last January, when a poll showed that 75 percent of Americans (including 53 percent of Republicans) were in support of raising the federal minimum wage. As the Atlantic points out, these raises follow increased pressure from labor activists, including the Fight for 15 movement that’s been pushing for a $15 minimum wage in major cities across the United States. In May, Los Angeles became the largest city in the country to raise its minimum wage to $15 an hour.

Most economists agree that this is a damn good thing. A 2014 Congressional Budget Office report found that raising the national minimum wage from the current $7.25 to $10.10 (a plan proposed by President Obama in his State of the Union address that year) would benefit some 16.5 million Americans, increasing total incomes of the more than 45 million living below the poverty line—and saving 900,000 from the crushing grind of economic hardship.

New York, with its seemingly piecemeal $0.25 wage increase, may be taking a long, thoughtful legislative slog toward a significantly higher wager in the future.

Opponents to the raise argue that these state legislatures, in fact, just doomed their constituents to an even more cutthroat battle for scarce jobs. The common argument against raising the minimum wage is that an artificial wage floor squeezes growing businesses, forcing them to re-allocate capital that could’ve been deployed for re-investment into paying their existing workforce—and, without time to adapt, downsizing low-paid employees like day laborers or seasonal workers.

Indeed, there’s some evidence to suggest this happens. As I wrote when Los Angeles adopted its $15 rate, the CBO report found that hiking the minimum wage to $10.10 would kill some 500,000 jobs nationally. Even a marginally smaller wage hike to $9 would still knock off some 100,000 jobs, according to the CBO. Additionally, hiking the minimum wage from $5.15 to $7.25 in 2007 may have actually kept one million people out of work when the Great Recession hit. On the federal level, opponents argue, a pay raise for many means a silent few have to suffer.

But that’s not necessarily true. An analysis from the Center for Economic and Policy Research found 12 of the 13 states that increased their minimum wage in January 2014 were still experiencing employment growth. This, in turn, helped the national unemployment rate drop from 6.5 to 5.5 percent.

This just underscores the problem of nationwide minimum wage policy: These states aren’t necessarily the same, and they each deserve policies that suit their own unique political, economic, and social ecosystems. A blanket minimum wage doesn’t uniformly affect every state economy; after all, Texas, Florida, and Pennsylvania have far more workers earning at or below the minimum wage than Connecticut, West Virginia, and Nevada, according to Labor Department data analyzed by Governing magazine. (Then again, perhaps those workers in Texas and Florida desperately need the hike, even though some of their colleagues will be squeezed out.)

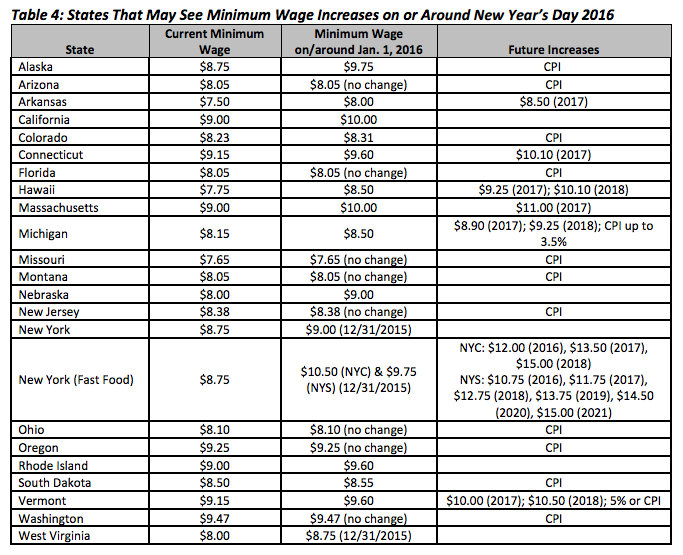

This is exactly what happened on January 1 of this year. States are addressing wage stagnation for the middle class with their own unique policy solutions. This chart from the National Employment Law Project shows the breakdown of the New Year’s change, including states that experienced minimum wages increases due to automatic measures:

And here’s where we get to the heart of our grand experiment: Do the businesses in these states have enough time to brace themselves for their various wage hikes? In reality, small businesses need time to build out “channels for adjustment,” which CEPR economist John Schmitt identifies as essential for various state economies to adapt to the sudden wage floor, like price increases and workforce adjustments. As I wrote in May, it’s the duration of the increase, not the wage jump itself, that’s the most important factor: Shorter implementation times and sudden shocks hurt business, but a long enough lead time to carve out those “channels of adjustment” made a wage hike bearable. A blanket federal minimum wage unevenly affects the disparate economies of different states, so even if businesses in Oregon have the time to build in those “channels of adjustment” and absorb the costs of a wage floor, businesses in Nebraska may not.

In reality, magnitude likely matters in a year-over-year wage hike, which suggests that businesses in California, Massachusetts, Alaska, and Nebraska may all feel the most pain, although the former two, with their relatively higher standards of living, may yield the least net gain to the average worker. By contrast, New York, with its seemingly piecemeal $0.25 wage increase, may be taking a long, thoughtful legislative slog toward a significantly higher wager in the future; New York Governor Andrew Cuomo did use the first business day of the new year to raise the wages for all State University of New York workers to that golden $15.

Either way, it will take some time to see how the impact of these wage increases shakes out in each state. Coming out of the holidays, the sudden unemployment of temporary seasonal workers and coming hiring of summer employees always distorts employment data. But compared to past experiments on the federal level, 2016’s grand experiment of state-level wage tinkering could help us better understand the macroeconomic impact of a higher minimum wage—and, as its advocates hope, pull hundreds of thousands of Americans out of poverty and destitution.