The one percent in America have an out-sized influence on the political process. What policies do they support? And do their priorities differ from those of less wealthy Americans?

Political scientist Benjamin Page and two colleagues wanted to find out, so they started trying to set up interviews with the richest of the rich. This, they noted, was really quite a feat, writing:

It is extremely difficult to make personal contact with wealthy Americans. Most of them are very busy. Most zealously protect their privacy. They often surround themselves with professional gatekeepers whose job it is to fend off people like us. (One of our interviewers remarked that “even their gatekeepers have gatekeepers.”) It can take months of intensive efforts, pestering staffers and pursuing potential respondents to multiple homes, businesses, and vacation spots, just to make contact.

Persistence paid off. They completed interviews with 83 individuals with net worths in in the top one percent. Their mean wealth was over $14 million and their average income was over $1 million a year.

Page and his colleagues learned that these individuals were highly politically active. A majority (84 percent) said they paid attention to politics “most of the time,” 99 percent voted in the last presidential election, 68 percent contributed money to campaigns, and 41 percent attended political events.

Many of them were also in contact with politicians or officials. Nearly a quarter had conversed with individuals staffing regulatory agencies and many had been in touch with their own senators and representatives (40 percent and 37 percent, respectively) or those of other constituents (28 percent).

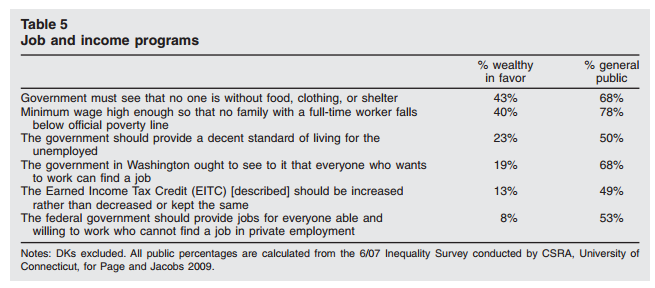

These individuals also reported opinions that differed from those of the general population. Some differences really stood out: the wealthy were substantially less likely to want to expand support for job programs, the environment, homeland security, health care, food stamps, Social Security, and farmers. Most, for example, are not particularly concerned with ensuring that all Americans can work and earn a living wage:

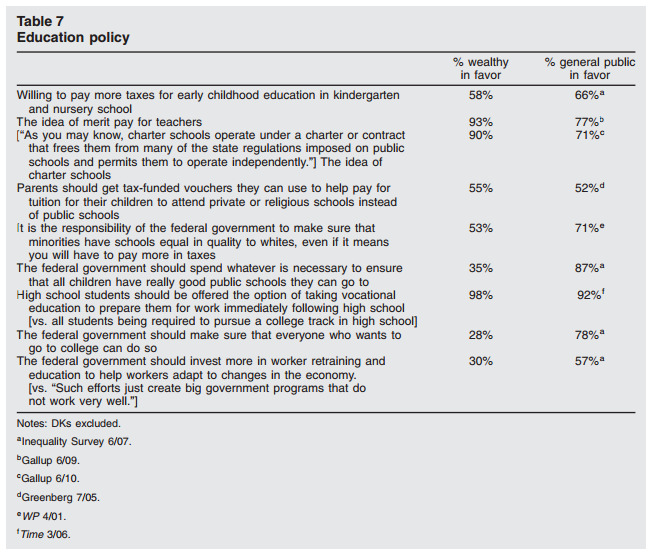

Only half think that the government should ensure equal schooling for whites and racial minorities (58 percent), only a third (35 percent) believe that all children deserve to go to “really good public schools,” and only a quarter (28 percent) think that everyone who wants to go to college should be able to do so.

The wealthy generally opposed regulation on Wall Street firms, food producers, the oil industry, the health insurance industry, and big corporations, all of which is favored by the general public. A minority of the wealthy (17 percent) believed that the government should reduce class inequality by re-distributing wealth, compared to half of the general population (53 percent).

Interestingly, Page and his colleagues also compared the answers of the top 0.1 percent with the remainder of the top one percent. The top 0.1 percent, individuals with $40 million or more net worth, held views that deviated even farther from the general public.

These attitudes may explain why politicians take positions with which the majority of Americans disagree. “[T]he apparent consistency between the preferences of the wealthy and the contours of actual policy in certain important areas,” they write, “—especially social welfare policies, and to a lesser extent economic regulation and taxation—is, at least, suggestive of significant influence.”

This story originally appeared on Sociological Images, a Pacific Standard partner site, as “What the One Percent Wants From Our Politicians.”